100 Objects from YIVO Reviewed by Ilan Stavans

by Ilan Stavans

In the mid-1980s, as a 25-year-old newly minted Yiddish-speaking immigrant from Mexico to New York, I had two institutions I was eager to be involved with: Forverts, the left-leaning Yiddish daily edited by Abraham Cahan, where Isaac Bashevis Singer, the author of Satan in Goray, The Slave, and Shosha, among other titles, published regularly stories, essays, and columns; and YIVO, the Institute for Jewish Research. In time, both of them became a home for me: I have contributed countless pieces to the English version of The Forward and occasionally the Yiddish one, too; and I have taught classes, lectured, and done research at YIVO — on Singer, among others, and, in part, for my book How Yiddish Changed America and How America Changed Yiddish (2020). The Yiddish word for home is היים, heym. Frankly, as a writer few things make me prouder. I feel as if, though these endeavors, I’ve been in dialogue with my ancestors, all dwellers from the Pale of Settlement, as well as with my successors. And there’s a bonus: part of my personal archives (photos, diaries, correspondence, manuscripts, etc.) is now housed at YIVO. (The other part is at UPenn’s Katz Center.)

YIVO is turning 100 this year. It was established in 1925 at a Berlin conference as Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut and headquartered in Vilna, Poland, now Vilnius, Lithuania. All kinds of luminaries have been associated with it, from historian Simon Dubnow and literary critic Shmuel Niger to lexicographer Alexander Harkavy and literary historian Zalman Reisen. Its initial Curatorium, or honorary board of trustees, included Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud. YIVO is also a metaphor for the centuries-old collective memory that refuses to die. As a research center, it emerged in response to Zionists who believed the Jewish diaspora had run its course and no longer had a function, although it has had every kind of enemy imaginable. Indeed, proof of its durability is that during the Second World War, the Nazis looted the YIVO headquarters in Vilna. Thanks to the U.S. Army, part of its collection was rescued and relocated to New York, in the nick of time (in 1940!). A new life in America began. Today aside from the New York branch there is a sister organization in Chicago, called the Chicago YIVO Society.

Given the current state of world affairs, and of Jewish culture specifically, more about the Jewish language wars must be said. The emergence of Israel as a Jewish state seemed to confirm, to its fervent supporters, that Yiddish was irrelevant thereafter. The Yiddishists, including those behind YIVO, opposed that ideology, or at least ignored it. While other Jewish languages like Judeo-Spanish, aka Ladino, Judeo-Italian, Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Persian, Judeo-Portuguese, and other tongues played a role in diaspora Jewish life, in terms of caché and influence, none ever competed against Hebrew and Yiddish.

The centennial of YIVO is proof that, contrary to what some argue, no one winner emerged from these language wars. To this day, Yiddish has no address, no flag, no post office, no national anthem, no government, and no army, but it has charm. Vulnerable? Of course it is, as well as endlessly resilient. It might have been described, including by Zionists, as a “dying dialect.” With between 1 and 3 million speakers today, most of them Haredi, that state—dying—seems permanent. The cycles continue: catastrophe is followed by revival and back, ad infinitum. In any case, Israel, its government and its mainstream national culture, still dismiss Yiddish as an anachronism, even though there is more room for it in the nation’s consciousness than before. Again, if scores are to be kept, writers in both Hebrew and Yiddish have received the Nobel Prize in Literature: Shmuel Yosef Agnon in 1966 and Singer in 1978, respectively. And countless diaspora Jewish authors have been awarded the Prize, including Nelly Sachs, Saul Bellow, Joseph Brodsky, Nadine Gordimer, Harold Pinter, Imre Kertész, Bob Dylan, and Louise Glück.

In my view, one of the biggest absences in the plentiful history of YIVO as an institution is the absence of a branch in Jerusalem or Tel-Aviv. There are other Yiddish-themed organizations in Israel, such as Beit Sholem Aleichem (“Sholem Aleichem” simultaneously means “Peace be with you” and refers to the legendary Yiddish author Solomon Rabinovich, responsible for the beloved classic Tevye the Dairyman, on which the Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof is based) and Beit Leivick, where, among other entities, the Association of Yiddish Writers and Journalists in Israel is based. These organizations, in their mission and resources, are modest in comparison with YIVO.

In contrast, there is a YIVO branch in Buenos Aires. Argentina, of course, is the other major epicenter of Jewish life in the Americas. Established in 1928 and called Fundación IWO, this branch was headed for a significant time by Samuel Rollansky, who published the valuable 100-volume Yiddish anthology Musterverk and was a columnist for the Yiddish-Argentine newspaper Di Yidishe Tsaytung. That branch itself was almost completely destroyed in the 1994 Iran-sponsored terrorist attack against the AMIA, the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina, as Buenos Aires’s Jewish Community Center is known, where Fundación IWO was located. 85 staff and patrons were killed and over 300 were injured, its archives diminished. Against odds once again, YIVO in Buenos Aires survives.

I finally come now to the occasion that prompted in me these reflections. As part of the worldwide celebration of the YIVO centennial is an exquisitely illustrated book called 100 Objects. It has an introduction by Stefanie Halpern, the Director of Collections at the New York branch. Being primarily a depository, the collection has approximately 385,000 items about Yiddish civilization, including all kinds of paraphernalia from the 16th-century. I have been in its vaults numerous times. It is a sight to behold. Some 40,000 of its volumes are in Yiddish, making this library the largest collection of Yiddish-language works on the globe. The Yiddish Book Center, in Amherst, Massachusetts, is another extraordinary archive. As an institution, it is also committed to teaching the language, introducing younger generations to its culture, and, significantly, digitizing Yiddish books in order for it to reach anyone everywhere all the time. In fact, thanks to the Center Yiddish is said to be the only national literature in the world fully available online.

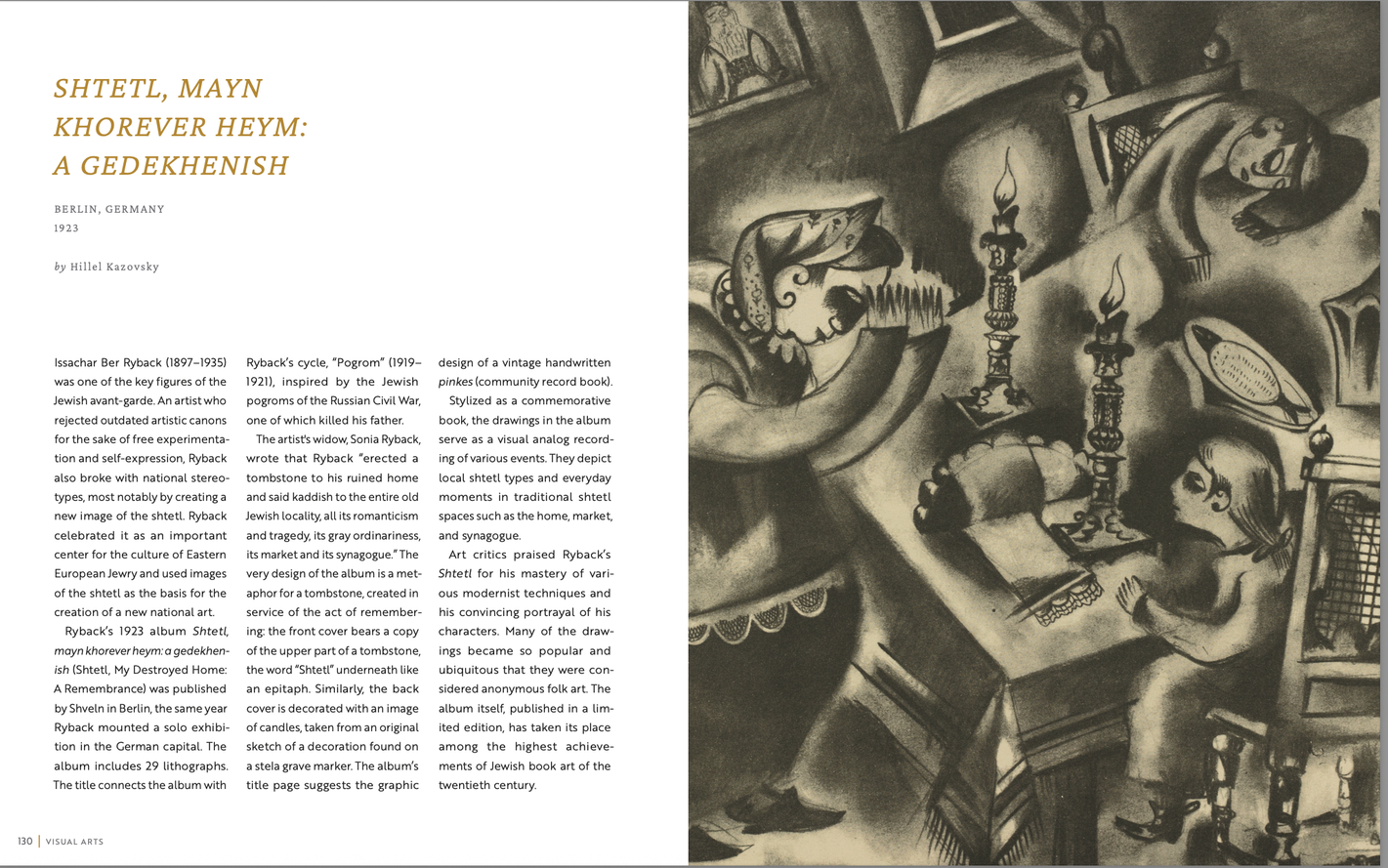

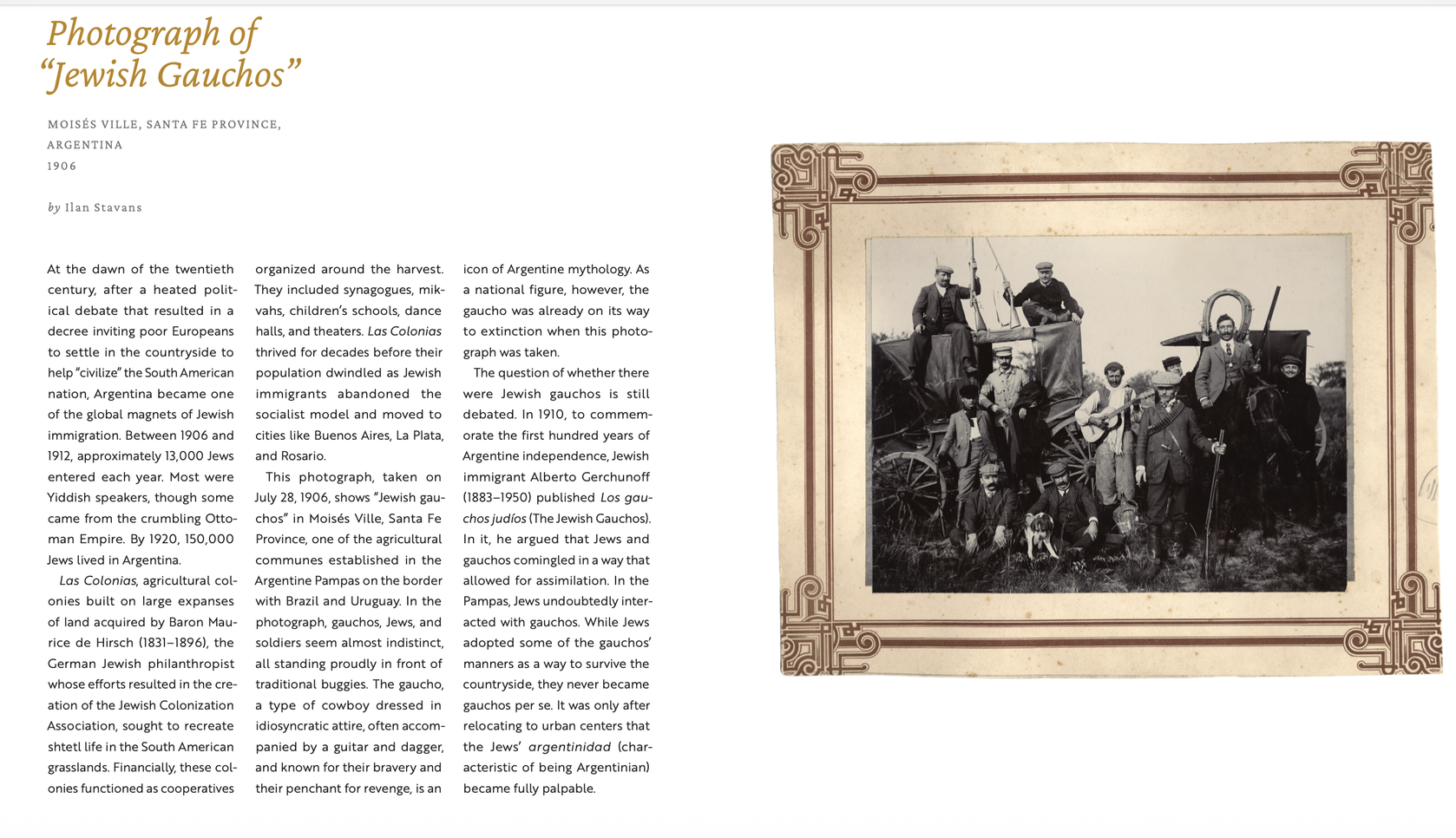

Choosing a hundred items in that abundance is, in and of itself, a daunting task. (Although I was about to write that I wouldn’t wish such a task on myself, it would be a lie; in fact, I dream of one day doing a history of Latin American Jews in 100 objects, several of which, I predict, would come from the YIVO collection.) Halpern and her staff have done an enviable job. The photographs of kheyder boys and their melamed from Lublin in 1924, a vitrine with faces from the theatrical adaptation of Israel Joshua Singer’s novel Yoshe Kalb from New York in 1933 (I.J. Singer was Bashevis Singer’s older brother); silver Torah ornaments from the Russian Empire in 1882 and 1892; hats used by International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union members, from New York in 1960; an elegy to the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 (in How Yiddish Changed America, I include the elegy to the Triangle Fire victims by Morris Rosenfeld); a copy of the book College Yiddish of 1949; and much more. Each of these images is accompanied by a brief essay by a Yiddish scholar or appropriate commentator, from Zachary Baker and Hasia Diner to Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Annie Polland. I wrote one for a 1906 photograph of “Jewish Gauchos” in Moisés Ville, Santa Fé Province, Argentina.

An archive, by definition, is a machine of nostalgia. Artifacts from any provenance, which would otherwise be discarded, acquire fresh meaning through their proximity. The personality of the collector is tangible everywhere, even though the voice of that collector is discreet, tangential, and ineffable. On the surface, the number 100, like any other, is arbitrary: in truth, it could have been 27, 623, 1,079, or 6,743. As a social convention, one hundred is familiar, concise, and well-rounded. It makes me think of the meaning of 1,001 in Arabic (ألف وواحد, pronounced alf wa-wahid), used in the title of the Arabian Nights that features tales about Aladdin, Sinbad, and Ali Babba and Forty Thieves. It goes without saying that the anthology of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories, known as The Thousand and One Nights, doesn’t really feature 1,001 nights. The number 1,001 simply implies “infinite.” The same might be said of 100 Objects, handpicked from the YIVO collection. These are meant to be any objects in it. They might be the most salient and representatives. Any such selection would be random. Therein its power and endurance.

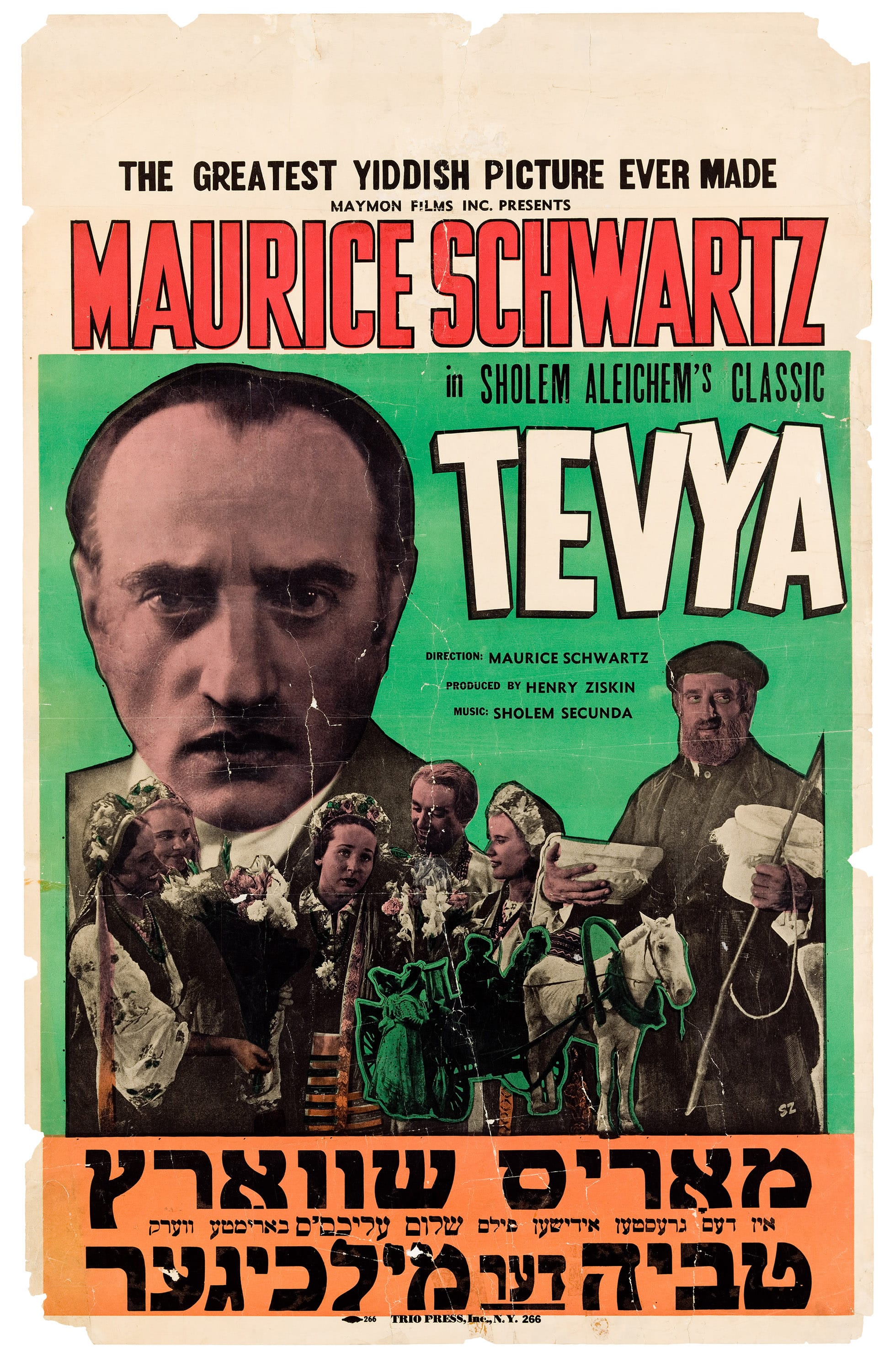

To bring the book to my reader’s experience, I want to reflect on a specific object that appears on page 112: a poster for the movie Tevya, dated in New York in 1939. The explanatory essay is by Alex Weiser, the Director of Public Programs at YIVO and a composer who has been a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Tevye the Dairyman has been adapted into film several times. This poster references the version—in Yiddish—by actor Maurice Schwartz, a beloved figure actor who founded the Yiddish Art Theater and was immensely popular among Jewish audiences on Broadway. The version is based on a stage version written by Sholem Aleichem himself in 1914 that premiered in 1919. It rotates around the character of Khave, Tevye’s third daughter, who converts to Christianity. The Yiddish film, itself an adaptation of that adaptation, remains an enormously popular movie. With a budget of $70,000, a large sum at the time, it was shot in Jericho, Long Island. As Weiser states, Tevye, his wife Golde, and their oldest daughter Tseytl sit shiva after Khave marries a goy. The plot thickens, though. Among other miseries, Khave is abused by her in-laws. As Tevye learns that all Jews, by a government decree, must depart the town in which they live, Khave leaves her husband to rejoin her family and Judaism. It isn’t quite a happy ending (no such thing is possible with Tevye) but audiences at least feel a sense of narrative roundness. More than memorabilia, the Tevya poster is a reminder that Jewish stories are endlessly replenishable.

If 100 Objects from YIVO has a limitation, it is that it overemphasizes certain geographical locations (Eastern Europe and the United States, particularly the East Coast) at the expense of others that are highlighted in recent scholarship. Yiddish was, from its inception, a global language, not constrained into a single location: from the Rhine River in the 10th century, it expanded across the continent and, through travelers, as far as China. Then, through immigration, it irrigated landscapes as diverse as Sidney, Australia; Mexico City; Cairo; Montreal; Baghdad; and New Delhi. Two people with otherwise little in common meeting for the first time at a bar in Havana would strike a conversation in mame loshn, e.g., mom’s lingo. By the way, the word “ייִדיש” (Yiddish) in Yiddish means Jewish.

Anyway, happy 100th birthday, YIVO: אַ פֿריילעכן געבורטסטאָג from a Mexican boychik.

_________________

Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College, the publisher of Restless Books, and an advisor to the Oxford English Dictionary. His latest book is Conversations on Dictionaries: The Universe in a Book (Cambridge University Press, 2025).

To buy the book: http://yivo.convio.net/100-Objects

READ all Ilan Stavans in New Mexico Jewish Journal, including Borges' Jewish Roots

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

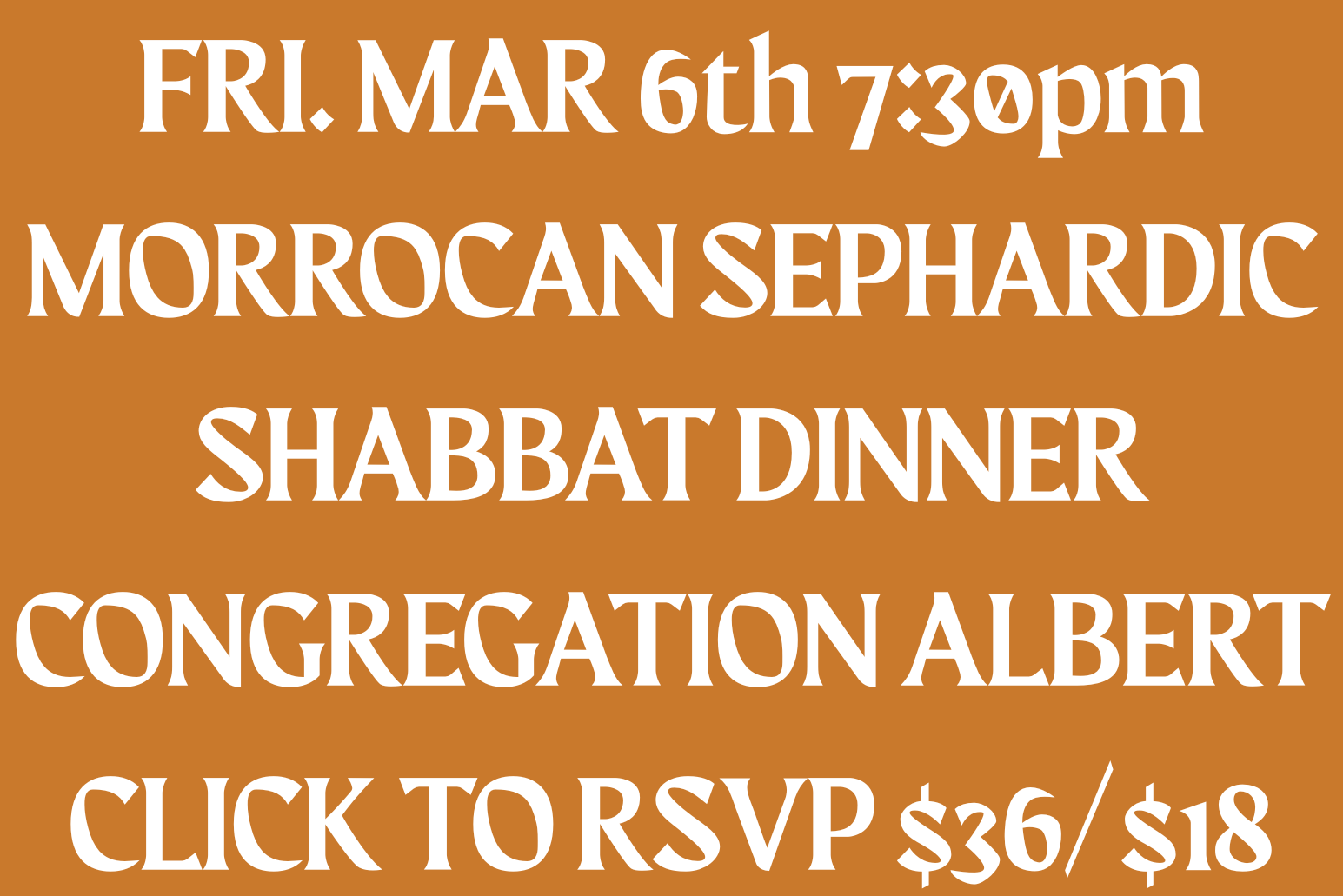

Congregation Albert

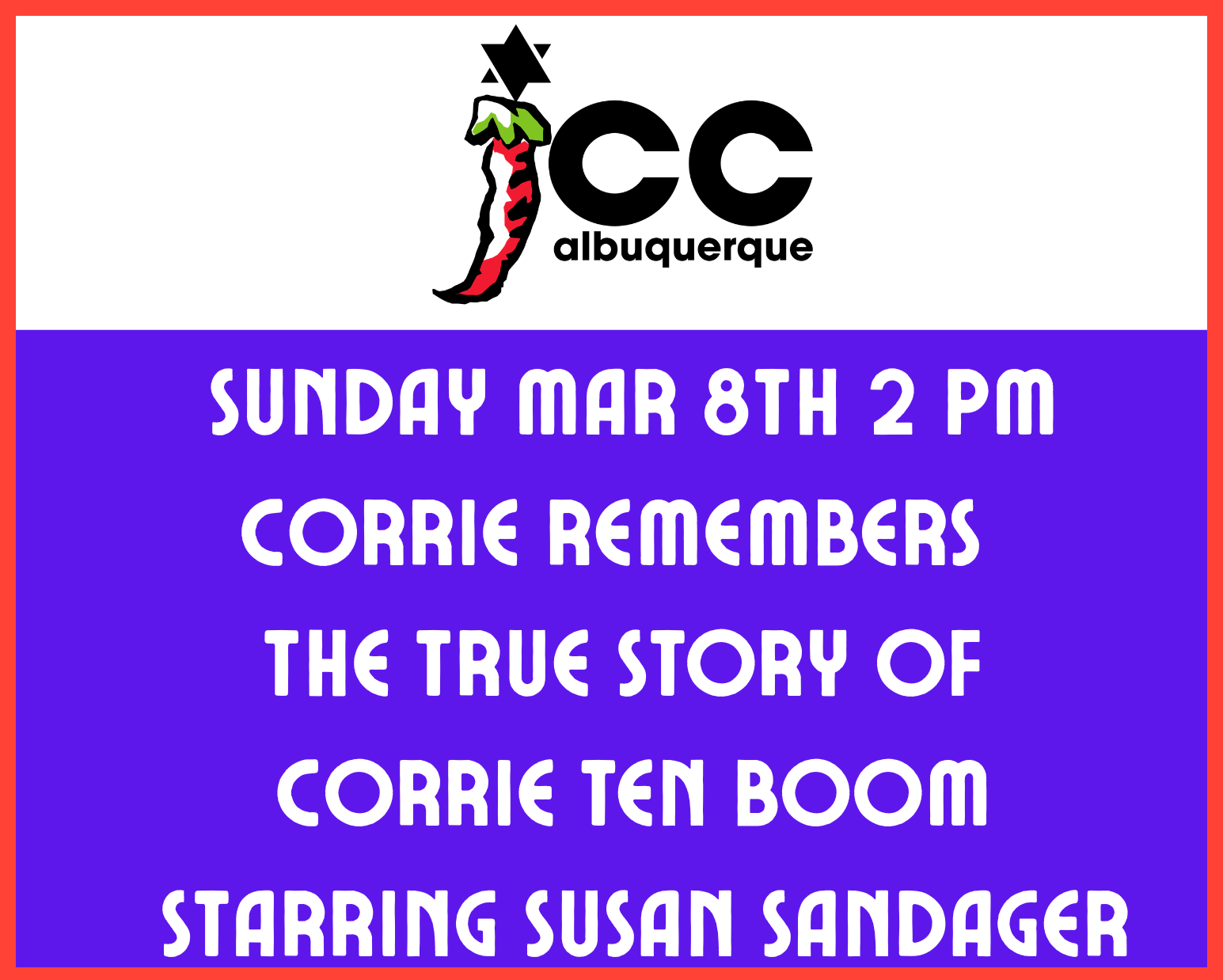

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

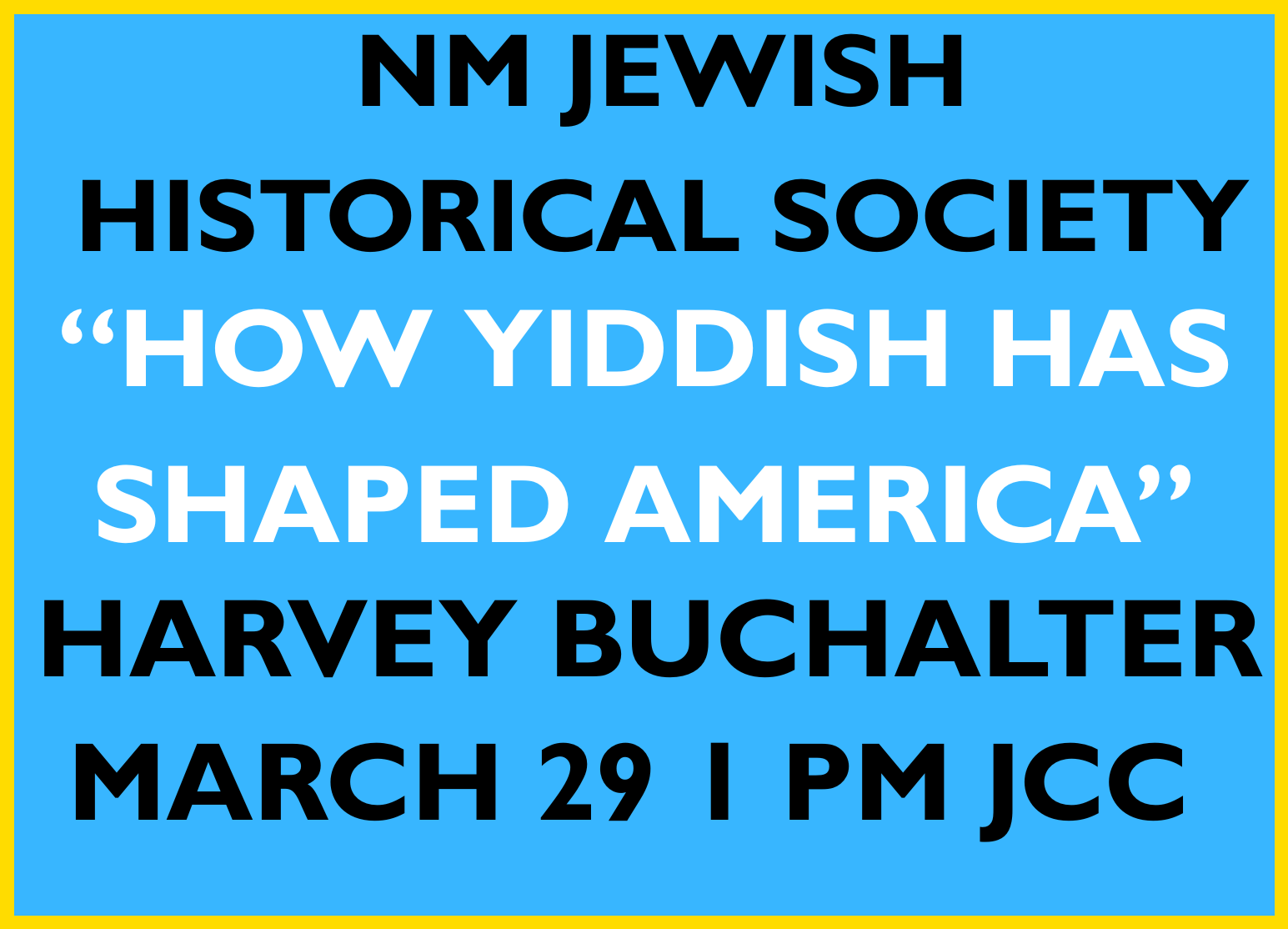

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

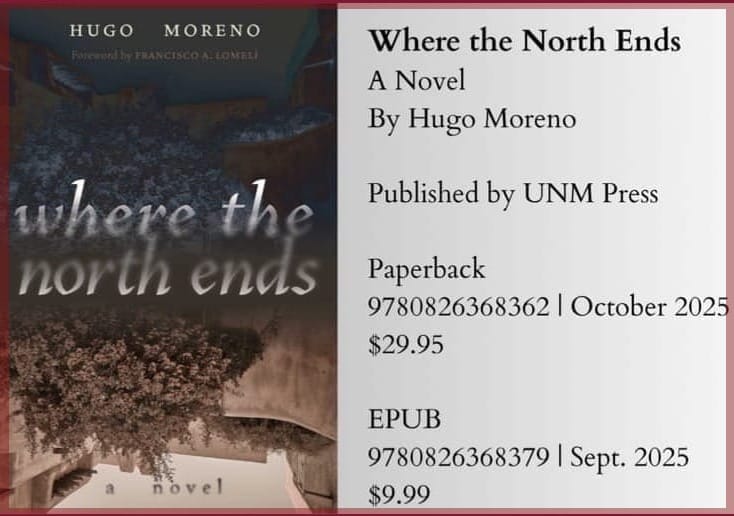

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.