Borges’ Jewish Roots

by Ilan Stavans

Perhaps because the adolescence of Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) was marked by the atrocities of the First World War—when his family was caught in Europe during a trip and ultimately stayed there for more than a year—and the friendships he made during the period, and because of the strong presence of Jews in Argentina starting with a wave of immigration from Yiddish-speaking shtetls in Eastern Europe in the nineteenth century, the theme of Jewish culture was dear to him.

Early in his career, during the 1930s, he was attacked in the magazine Crisol for being a Judeophile. Rather than being offended by the accusation, he cherished it. He states in “I, a Jew” (1934): “Who has not, at one point or another, played the thoughts of his ancestors, with the prehistory of his flesh and blood? I have done so many times, and many times it has not displeased me to think of myself as Jewish. It is an idle hypothesis, a frugal and sedentary adventure that harms no one, not even the name of Israel, as my Judaism is wordless, like the songs of Mendelssohn.” Borges concludes the piece thus: “Statistically, the Hebrews were few. What would we think of someone in the year 4000 who uncovers people from San Juan Province everywhere? Our inquisitors seek out Hebrews, but never Phoenicians, Garamantes, Scythians, Babylonians, Persians, Egyptians, Huns, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Ethiopians, Illyrians, Paphlagonians, Sarmatians, Medes, Ottomans, Berbers, Britons, Libyans, Cyclopes, or Lapiths. The nights of Alexandria, of Babylon, of Carthage, of Memphis, never succeeded in engendering a single grandfather; it was only to the tribes of the bituminous Dead Sea that this gift was granted.”

Anti-Semitism and Nazism constantly appear in Borges’ stories, essays, and poems. Between 1937 and 1945, he reflected on the destruction of European Jewry. Though none of his pieces get inside a concentration camp, let alone a crematorium, they reflect, with acumen, the plight of a civilization driven to near extinction. Borges wrote about a dozen pieces on the subject, along with three or four short stories. In “A Pedagogy of Hatred” (1937), he describes Nazism as an ideology founded on hate and based on despicable ideas that justify anti-Semitism. “An Essay on Neutrality” (1939) is clear about the impossibility of being neutral at a time when Hitler and his forces are broadcasting hatred across Europe. Borges calls Hitler’s plans the “atrocious offspring of Versailles.”

Likewise, in “Definition of a Germanophile” (1940), Borges reflects on those who adore the ideology of Germanophilia as an opposite of Anglophobia. “1941” (1941) reflects on the universal empire the Third Reich seeks to create, including South America, and announces how miserable it is likely to be. And “A Comment on August 23, 1944” (1944) marks the liberation of Paris and the approaching end of the Second World War. What he cherished at the conclusion of the conflict was the return to order. “For Europeans and Americans, one order and only one is possible; it used to be called Rome, and now it is called Western Culture.” Later on, he adds: “Nazism suffers from unreality .... It is uninhabitable; men can only die for it, lie for it, wound and kill for it. No one, in the intimate depths of his being, can wish it to triumph.” These pieces are tangible evidence of Borges’ public views on the Second World War. Rather than spending the war years as a hermit, as his critics frequently described him, an aloof thinker uninvolved in earthly matters—such as politics—he was always up-to-date about the conflict. While he carefully calibrated his words, the select statements he did issue are consistent. Others in Argentina fell in line with the Germanophile fever, but he took the opposite stand.

The story “The Secret Miracle” (1943) is about a Jewish poet, scholar, playwright, and translator in Prague arrested by the Nazis for being a Jew. It begins on March 14, 1939. Borges locates the plot on Zeltnergasse, which is where Franz Kafka, one of Prague’s most illustrious citizens, lived. Hladik, his protagonist, is the author of a number of monographs, translations, and treatises, but he wants to be remembered as the author of the drama The Enemies. At the beginning of the story, he dreams about a chess game that has been played since time immemorial. The two contestants no longer know why they are in the game. Soon after, Hladik is arrested by the Nazis. In his cell waiting to be executed, he asks God for a secret miracle: that before he dies he be given the opportunity to conclude his lifelong project, The Enemies, which he believes justifies his existence, and, as a result, that of God as well. The following day, in front of the firing squad, a “secret” miracle takes place. Just as the triggers are pulled, the entire universe comes to a halt. “Upon a courtyard flag stone,” the reader is told, “a bee cast a stationary shadow. The wind had halted, as in a painted picture. Hladik began a shriek, a syllable, a twist of the hand. He realized he was paralyzed. Not a sound reached him from the stricken world.”

Hladik realizes that he has been granted a year to complete The Enemies — not the actual cycle of a literal year but instead a “personal” year. In that period, he is able to conclude his play. Time in the story manifests on two dimensions: the natural and the psychological. In the natural world, Hladik dies the moment the rifles go off; in the mental dimension, time has its own rhythm, elongating in order to satisfy his internal needs. Borges’ view on anti-Semitism is that such hatred might annihilate people but not ideas. Jews like Jaromir Hladik are martyrs. They are models for continuity. Memory isn’t made of reminiscences alone, but rather is collective, traveling from one generation to the next.

Another story in which Jewish characters are targeted is “Death and the Compass” (1944). It is designed as a tacit tribute to the geometrical interests of Baruch Spinoza, author of The Ethics. In truth, the setting is a proxy for Buenos Aires. The protagonist is Erik Lönnrot, a seasoned detective whose career has been devoted to trapping his archenemy, Red Scharlach. Lönnrot uncovers a series of crimes from which he deduces a careful geometrical plan: each crime was committed on the same day of successive months (December 4, January 4, and February 4 of the Hebrew calendar), in locations at three of the four cardinal points in the city. All the victims are Jews and at each crime scene another Hebrew letter is written by the criminal. After the first three crimes, Lönnrot comes up with the date, time, and place of the fourth crime. As soon as he arrives at the location, he realizes that Scharlach is the perpetrator and that he himself is meant to be the fourth victim.

There is also “Emma Zunz,” about a young Argentine Jewish woman who early in the plot finds out, through a letter sent from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, that her father, Manuel Meier, a.k.a. Emanuel Zunz, has recently died by accidentally ingesting an overdose of the barbiturate Veronal. Emma Zunz senses that this wasn’t an accident but instead a suicide, and that the person who drove her father to such a decision was his business partner, Aaron Loewenthal. She understands that Loewenthal orchestrated her father’s death in order to take control of the business and that no one is likely to know this detail, and thus Loewenthal won’t be brought to justice. She therefore decides to take the law into her own hands by exacting revenge in an equally surgical fashion.

The story features a horrible sexual scene in which Emma, the victim, “thought (she could not help thinking) that her father had done to her mother the horrible thing being done to her now.” Although her sexual encounter is technically consensual, it might be said that Emma Zunz plots her own rape. The critical passage goes: “To recount with some degree of reality the events of that evening would be difficult, and perhaps inappropriate.. . .How to make plausible an act in which even she who was to commit it scarcely believed? How to recover those brief hours of chaos that Emma Zunz’s memory today repudiates and confuses?”

She is a virgin. In order to commit the crime that she has set herself, she decides to lose her virginity, goes to the nearby pier, finds an anonymous sailor, and subjects herself to the abrupt sexual act. Afterwards, she goes to Loewenthal’s office. The workers at Tarbuch & Loewenthal are in the middle of a strike. It is already night when she finds he is alone. She knows he keeps a gun in his desk drawer. They have a conversation. She then pulls out the gun and shoots him. Emma Zunz calls the police to say: “Something has happened, something unbelievable. . . .Sr. Loewenthal sent for me on the pretext of the strike. . . .He raped me. . . .I killed him....” The plot was given to Borges by his friend Celia Ingenieros. Emma Zunz (her four-letter first and last names suggest the Tetragrammaton) is ready to sacrifice herself—lose her virginity through a horrific sexual act—to find in herself the necessary emotion to accomplish her task: killing the man who drove her father to suicide. She orchestrates her actions so that she is able to deliver a believable alibi to the police.

Other stories by Borges deal with Nazism, including “Deutsches Requiem” (1946), a fictional confession by an SS officer, Otto Dietrich zur Linde, imprisoned in the same cell with a Jewish victim, David Jerusalem.

Borges’ relationship with the state of Israel is a useful theme when it comes to nationalism. After the creation of the state in 1948, he appeared befuddled by the need of the Jewish people to have a “normal” life like everyone else: with their own homeland, their own language (a “resurrected” version of biblical Hebrew), their own flag, anthem, army, central bank, post office, and so on. What he deeply admired about the Jews was their diasporic journey, the capacity to be both insiders and outsiders in different countries, speaking a multitude of tongues, connecting to texts and collective memory as a strategy of survival. In a series of poems about Israel, he championed what he saw as “an old nation reborn.” He visited Israel on a couple of occasions, on one of them receiving the Jerusalem Prize.

Yet Borges was skeptical of Israel’s early nationalist efforts. As in the case of Argentina, he saw militarism not as a distraction from worthier social, political, and economic endeavors; he also believed nationalism (call it Nazism, Stalinism, Peronism, or a variety of other -isms) to be antithetical to balanced, cordial relationships, not only with one’s neighbors but with one’s self. In his view, nationalism leads to a narrowing of the imagination. For him, nationalism was a version of hell. Indeed, in “The Total Library,” Borges writes: “One of the habits of the mind is the invention of horrible imaginings. The mind has invented hell, it has invented predestination to hell, it has imagined the Platonic ideas, the chimera, the sphinx, abnormal transfinite numbers (whose parts are no smaller than the whole), masks, mirrors, operas, the teratological Trinity: the Father, the Son and the unresolvable Ghost, articulated into a single organism....” Having himself lived through versions of that hell, individual as well as collective, he didn’t shy away from calling it as he saw it.

Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College, the publisher of Restless Books, and a consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary. This excerpt comes from chapter 4, “The Taxonomy of Evil,” of his recently-published book Jorge Luis Borges: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press) Publication date: June 30, 2025. Stavans’ next book is Conversations on Dictionaries: The Universe in a Book (Cambridge University Press), out in October.

Of further related interest to readers by Stavans:

Borges, the Jew in the Jewish Review of Books

Jewish Literature: A Very Short Introduction (2021): Jewish Literature: VSI.

TED-Animation: The Magical Fictions of Jorge Luis Borges

Bio: Ilan Stavans

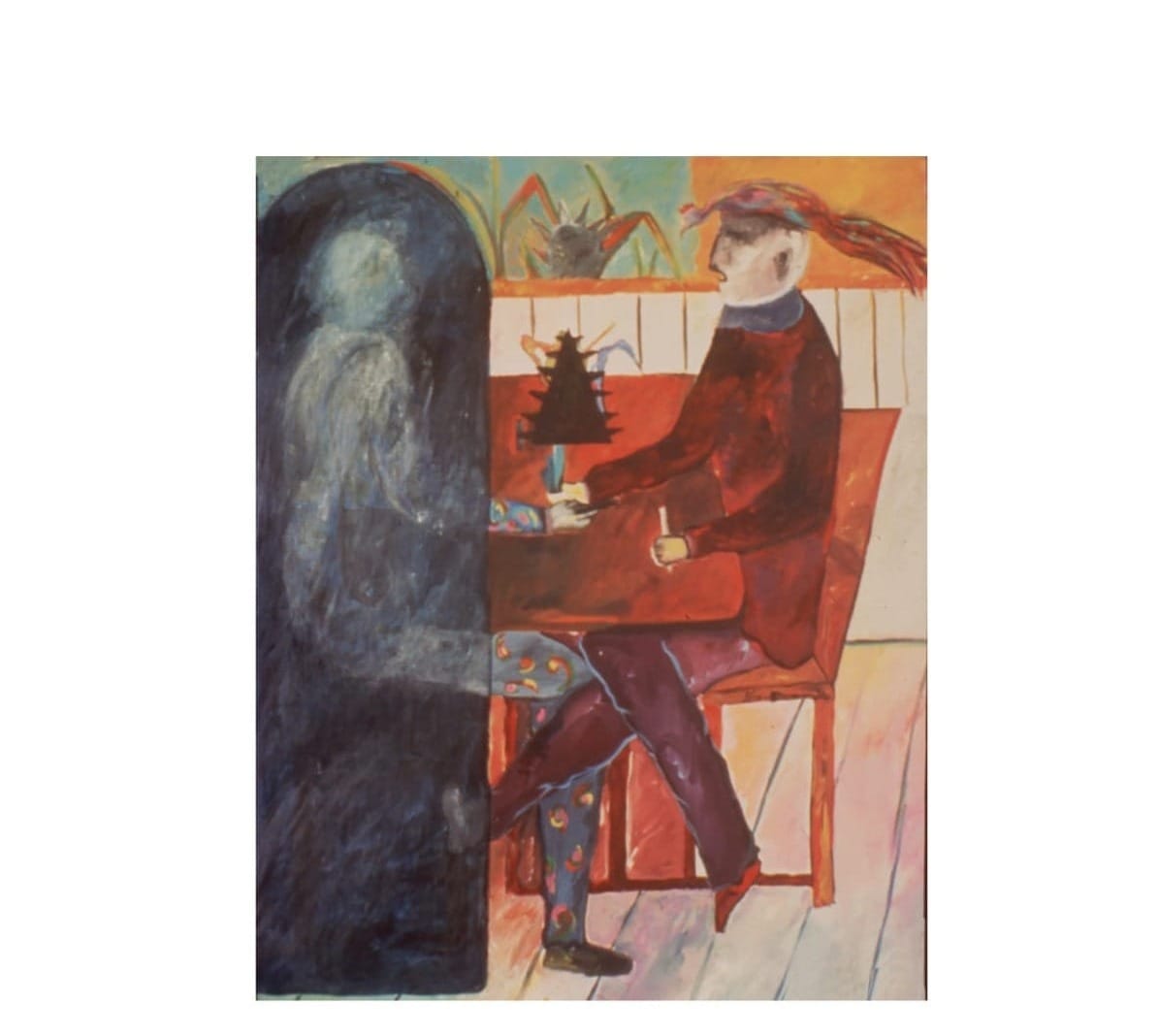

Gloria Abella Ballen selected her painting "Is It A Dream?" which plays, ghostlike, with reality and illusion, to accompany "Borges' Jewish Roots." She and Ilan Stavans collaborated on The New World Haggadah (Gaon Books), nominated for the National Jewish Book Awards, and 1st Place Winner, Arizona-New Mexico Book Awards, Religion. Visit https.//www.abellaballen.com.

Return to HOME

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.