DINÉ POETICS, Poetry Magazine, Guest Editor Esther Belin

Review by Anna Redsand

In the first weeks of the current US administration, photos of World War II Diné (Navajo) Code Talkers were removed from US military websites. Due to intense protest, the images were later returned. In the meantime, the Poetry Foundation published something extraordinary, which turns out to be the opposite of this attempted erasure. Its entire March 2025 issue of Poetry Magazine showcases the poetry and poetics of Diné poets, as well as the work of a few other Indigenous writers. What the current administration did was not a first in US history; for centuries, through actual genocide, language policies (referred to by some as "linguicide"), forced boarding school attendance, and the list goes on, the federal government has sought to erase Indigenous people literally and figuratively. The Poetry Foundation's bold March issue stands in striking contrast to those actions.

The editor of this outstanding issue, Diné poet Esther Belin, has given voice to past and present Navajo Nation poet laureates, to emerging poets, and to writers whose work has not previously appeared in Poetry Magazine. The volume offers an astonishing array of work: visually gorgeous calligrams, narrative poems, two foldouts to accommodate formats that fall outside its page-size, and more. Many poems are bilingual, but how they are bilingual varies with a diversity that is pleasurably challenging to both the eyes and ears: Entire poems appear in Diné bizaad (the Diné language) with English translations on facing pages; poems may be translated verse-by-verse on the same page; in other poems Diné bizaad is interspersed with English, sometimes translated, sometimes left to the reader's knowledge or imagination. There are also prose pieces, devoted to an exploration of Diné and other Indigenous poetics. The volume closes with a roundtable discussion of Indigenous poetics.

In the process of considering poetics, the essays and the roundtable delve into such a broad and deep exploration of the linguistics of the creation of poetry, that I am hard put to make a container for all that it illuminates. An example is the inquiry into the intersection of Diné bizaad with English, the language of colonization. This collection of works advances a stunning amplification of our understanding of the meanings and possibilities of language in the cross-pollination that occurs when unrelated languages begin to relate. The meaning of poetics is greatly expanded to include dance, picto-poems, beading, hide paintings, songs, maps––mapping "identity, relationships and meaning via more than words," as Kimberly Blaeser (White Earth Anishinaabe) and founding director of Indigenous Nations Poets, puts it.

A stellar example of this expansiveness is found in Manny Loley's (Diné) "From the Mesa," in which he reflects on "saad," which is most frequently translated "word," "language," or "speech," but as he writes, "Saad is breath. Saad is reciprocity. Saad is manifestation. Saad is possibility." He points out that "saad has a physical aspect through the human breath, which essentially feeds plant life through the emission of carbon dioxide." This relationship has been part of Diné teachings for hundreds of years, predating the European recognition of oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange with plants, in the late 1700s.

In her essay, "I Am Dressed in My Language," the second Navajo Nation Poet Laureate (2015-2019), Laura Tohe, tells the story of how she developed as a poet, of how "Poetry freed me from the mold of English-only," how the first time she wrote a poem in Diné bizaad it "found its own form," that "there seemed to be an airiness to it, like words were feathers." She writes mainly in English now, although she finds that Diné words and expressions add meaning and depth to her work. The inaugural Navajo Nation Poet Laureate (2013-2015), Luci Tapahonso, mirrors Tohe's experience when she writes that her early stories in English felt "skinny" and "hungry."

Esther Belin's editor's note is itself a treatise on the relationship between poets' uses of English and Indigenous languages. She relates how English, originally forced on the Diné people, is now being "reconstructed with Diné sound and thought," which can often be heard in the cadence of these works. She points out that "the English language can also be a preferred vessel for Dinétics because of the sacred qualities of Diné bizaad," providing us with a critical insight into literary choices.

A thread that runs through the poetry and prose of this volume is the revitalization of Diné and other Indigenous languages, all of which are, to differing degrees, struggling to stay alive. While recently working on a Diné bizaad revitalization project, I was repeatedly reminded of the work of Eliezer Ben Yehuda, a major figure in the revival of Hebrew into the living, day-to-day language of Israel. These Indigenous poets speak and write of how creating new forms in their languages––writing poetry and text messaging, for example––are injecting new vitality into their mother tongues. Beth Piatote (Nez Perce) says, "Storytellers and writers have a particular role in carrying the language forward because we are gifted with a relationship to language––its structure, its sound, its meaning." I wondered, reading this, about the role poets may have had in developing modern Hebrew. In fact, cursory exploration shows that Israeli poets sparked early interest in Hebrew's potential as a living language, suggesting that a comparison of poets' influence on revitalization of various tongues could be a fruitful topic for further study.

The poems that most captivated me were those that embodied what I recognize as a unique brand of Native humor––sometimes dark, sometimes satirical, at other times tender and loving, sometimes requiring inside knowledge. Often it makes fun while simultaneously exposing the seriousness of the places where life today crosses the myths and realities of history, where past and present collide, as they do in Hershman John's (Diné) poem "Lost Quails in an Easter Pastoral." I delighted in his naming the stories of Easter, "magical realism," placed within an extended metaphor. Cheyenne Dakota Williams's (Diné) "Heritage Diner," and Nicole Gonzalez's (Diné/Chicana) "Magic Eight Ball" treat us to the haunting, dark comedy in the collision of the post-modern with the post-colonial. These choice poems are evocative of what also takes place in much Indigenous visual art these days––where contemporary style meets traditional themes and blends both with modern life, often in a spirit of tragi-comedy.

I am not overstating it when I say that the lavish spread of poetry and generous Indigenization of poetics make this volume a must-read. In "Memories of Allegiance," Shaina A. Nez (Diné) says it:

... Reciting the pledge of

allegiance in Diné bizaad was the first time I ever felt

whole alive for once my nalí understood me I

made them proud there was hope for me no one said

our language emphasizes abundance much more than

the United States can afford much more than

war language much more than our recognition...

This magnificent, heroic issue of Poetry Magazine is available online at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/issue/1651121/march-2025 and also for single, hard-copy purchase.

Following this issue's practice, I have not italicized words written in Diné bizaad (the Navajo language).

Anna Redsand is a Bilagáana (White) woman who grew up in the Navajo Nation, the daughter of evangelical missionaries. She worked in Diné education as an educator, bilingual curriculum writer, and linguist. Her most recent book, Crevice: A Life Between Worlds won the Kenneth Johnston Nonfiction Book Award. In the topical monograph Honoring Our Indigenous Languages, Anna co-authored an article with Louise Benally on a Diné bizaad revitalization project. Her other books include To Drink from the Silver Cup and Viktor Frankl: A Life Worth Living. Visit her website at www.annaredsand.com

Read about Anna Redsand's new book, Crevice: A Life Between Worlds

Return to HOME

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

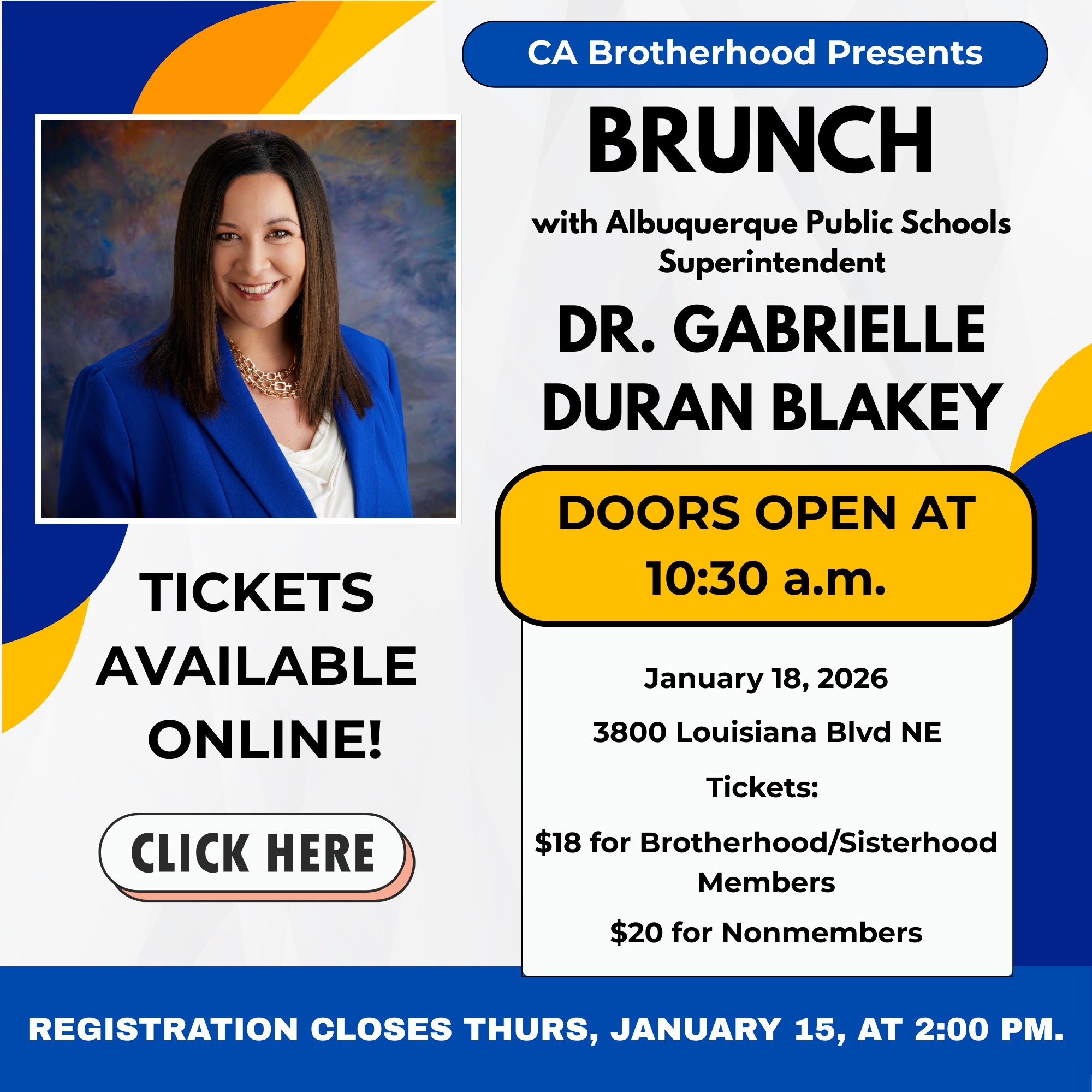

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

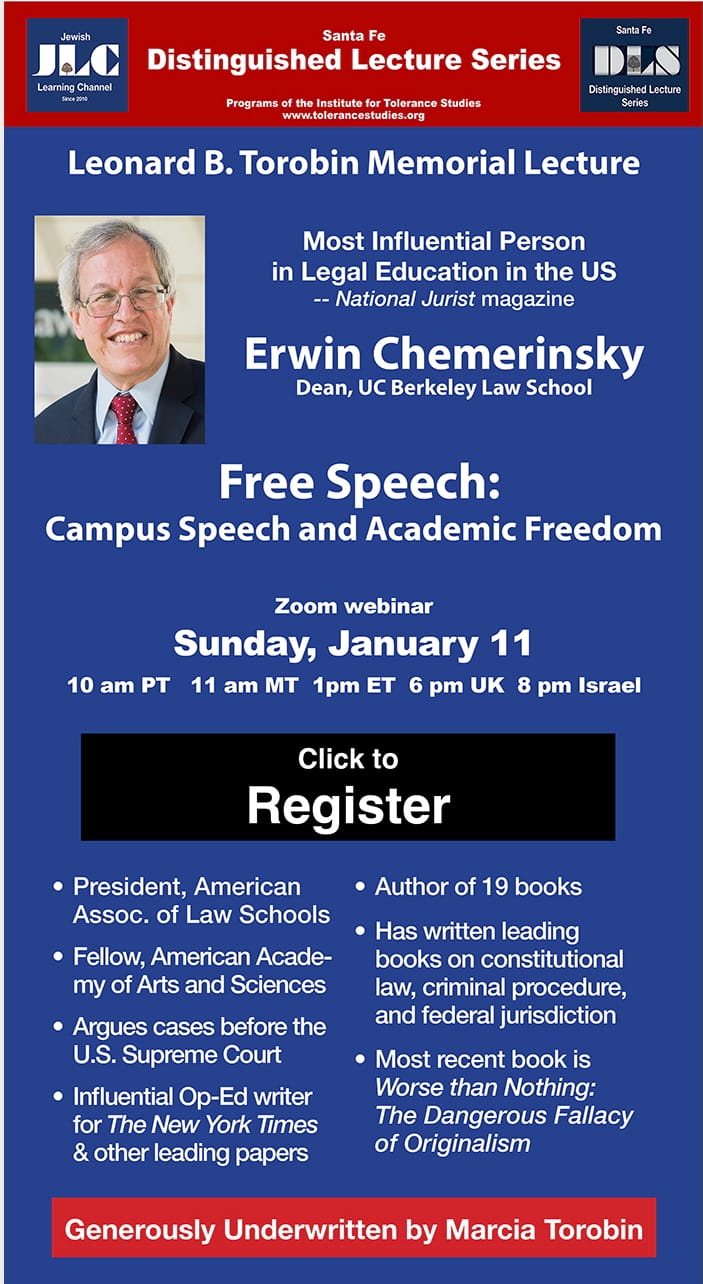

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

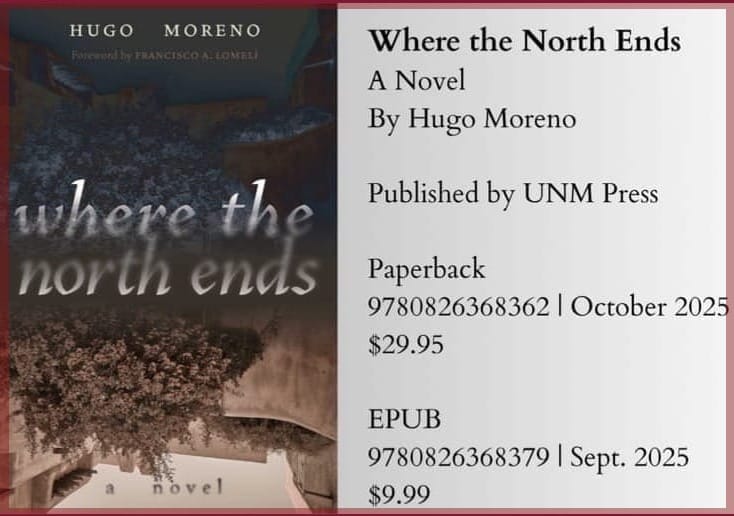

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.