Hidden in Plain Sight, Unearthing the Subterranean Mikveh of Ortigia, Sicily

Story and Photos by Lena S. Keslin

“To have seen Italy without having seen Sicily is not to have seen Italy at all, for Sicily is the key to everything.”

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1816

My friend, Judith Zorzy, had been telling me about the beauty and history of Ortigia for several years, but I had no idea of its Jewish history until my husband and I decided to go there to visit my old friend, who was spending the winter there. I never expected Ortigia to be as impactful or as captivating as it was, or that we would want to return there several months later.

The island of Ortigia is surrounded by the clear, turquoise waters of the Ionian Sea, with two small bridges that connect it to the mainland of Sicily and the city of Siracusa (Syracuse). I was surprised to find out that a thriving Jewish community, the Guidecca, of between 5,000 and 12,000 Jews, once called Ortigia home. The first record of Jewish settlers is from approximately 70 CE, after the Roman destruction of Jerusalem, when Jews were brought to Sicily as slaves. It is even possible that some Jewish merchants and traders resided in the area even before this. Today the Guidecca still exists but without its Jews, who were expelled, converted, or executed during the Spanish Inquisition, which occurred in 1493 in Ortigia. Naples, southern Italy and Sicily were then under Spanish rule and were thus subject to the Alhambra decree, which was issued in Spain in1492. The period of Spanish rule eradicated the Jewish people, but, as I was to learn, their history was not completely erased.

In 1986, an Italian woman, the Marchesa Amalia Daniele di Bagni, purchased an abandoned building in Ortigia’s historic center of the Guidecca. The building was totally dilapidated and filled with decades of garbage. Amalia took several years to renovate the old palazzo. As the construction continued, she became curious about a mysterious, windowless building in the courtyard. She couldn’t figure out why it was there and couldn’t find any access into the structure. With some help, she made a hole in the wall and found a small room, and after clearing out more debris, the mystery began to reveal itself. Amalia discovered a long and steep staircase with three flights of precarious, hand-hewn stone steps. There were 58 steps in total, descending 60 feet below the street level. The space was filled with mud and water that took 156 truckloads to remove, and when it was cleared out, she was amazed at what she had uncovered.

The mysterious wall that leads to the Mikveh and the ancient stone staircase, 60 feet below street level. Photos © by Lena S. Keslin / nmjewishjournal.com

In front of her was an ancient hypogeum, a subterranean chamber with stone columns and a vaulted ceiling. Amalia had unearthed one of the oldest Jewish Baths, or “Mikveh,” in all of Europe. The Mikveh dates to the sixth century, or possibly before, and had remained hidden since the Inquisition—for nearly 500 years. The Mikveh is comprised of three separate, personal-size pools, with steps leading into the dark-green water. On both sides of the room are two additional Mikvehs, a total of five pools. The water is still delivered from the same ancient freshwater spring running beneath the city of Ortigia.

Amalia’s research began with the knowledge that her building was in the Guidecca, and she was able to find documentation in some ancient books indicating that, during medieval times, her building had been the home of the Jewish Bianchi family. She also located two stones with Hebrew inscriptions. One was nearby in the former synagogue, now the Church of San Giovannello (St. John the Baptist). The translated Hebrew inscription read: “To the Synagogue of Siracusa, founded with justice and faith.” That stone has since been plastered over, and the church prefers not to mention its Jewish past. Thankfully, there is still the Hebrew-inscribed stone at Amalia’s Alla Guidecca, now a boutique hotel, with an inscription of the prayer to be recited before entering the Mikveh.

Ortigia is a maze of stone paved streets winding through neighborhoods of colorful buildings along the narrow paths. While exploring the Guidecca, I wondered what it had been like before the Inquisition, when the Jews were 25% of Ortigia’s population. I imagined Jews going about their business—the butcher, the weavers, the spice and silk merchants, the scholars—all contributing to their community, honoring the sabbath and holidays. My husband and I walked the narrow, cobblestone alleyways that still retained their Jewish history by the names of the streets: Via Della Guidecca, street of the Jews; Via Tintori, street of the Jewish fabric dyer; Vicolo Alla Guidecca, alley of the Jews. Now, Amalia has added a newer sign, Bagno Ebraico, for the more recently discovered Jewish Bath.

The potted plants on the narrow streets and alleyways of Ortigia and the tile rooftops above the Mikveh. Photos © by Lena S. Keslin / nmjewishjournal.com

This ancient Mikveh was once considered to be the most sacred place for the Jews of Ortigia. The Mikveh was most often used by women after their monthly menstruation, after childbirth or before marriage. One would always be thoroughly clean before her immersion, for the purpose of the Mikveh was to achieve spiritual purity or renewal by submerging oneself in a pool of water from an underground spring; it is a sacred act that is fulfilled monthly by women and, occasionally, by men. The Mikveh was just as important as a synagogue, often preceding the presence of a synagogue. And it's very possible that the original synagogue was located directly above the Mikveh, in Amalia’s Alla Guidecca.

In 1493 the Jewish community of Ortigia, in their final act to protect their Mikveh from desecration, buried it with earth and mud, where it would lie hidden from view for approximately 500 years, until Amalia Daniele di Bagni became curious. Her discovery has changed the understanding of Jewish history in Sicily. Scholars and academics come from all over the world to visit the Mikveh. For me, getting to see and experience the Bagno Ebraico was very emotional. On our first trip there, we were not permitted to take photographs, which was a real disappointment for me, but I persevered. As I carefully maneuvered down the slippery and damp stone steps, there was a feeling of anticipation. Suddenly, I was at the bottom of the stairs, 60 feet below the street level. Before me was the beautifully vaulted stone ceiling, with droplets falling into the pools of dark, emerald-green water that glistened in the subdued light. The tan, gold-hued stone glowed, reminding me of stonework I had often seen in Israel.

The experience stayed with me for months, long after our visit. At night when I couldn’t sleep, I imagined all the different passageways between Amalia’s building that housed the Mikveh to what had been the synagogue. I even wrote to the hotel and asked them if there was a secret way between the two buildings. They wrote back that there was not.

I knew I had to go back. I had to meet Amalia, and I had to photograph the Mikveh and have some of my questions answered. And so we returned to Ortigia at the beginning of November 2025. We had traveled so far to meet Amalia, and in my own, not perfect but heartfelt Italian, I told her how grateful I was to her for her discovery and subsequent research about the Mikveh and the Jewish history of the area. She was elegant and very gracious and welcoming. She answered my questions and the next day showed me the courtyard and what had once been the doorway that led from the home of the rabbi and the Mikveh to the synagogue. The doorway had been boarded up at the time of the Inquisition, and now there is just a decoratively tiled part of the wall that hides what had been the passageway between these two important buildings of Jewish life. It was exciting and validating to know that my instinct was correct. There had been a passageway.

At night my husband and I made our way back to the candlelit courtyard, surrounded by an abundance of flowering plants and tall trees. The top of the courtyard opened to the sky and had what resembled a sukkah, with slats of thin tree limbs and branches forming a protective shelter under the stars. I walked over to what had once been the passageway to the synagogue, and I stood there trying to let my imagination take me to the other side. For a brief moment I felt as though I had been transported to Israel, to Jerusalem, and I imagined the people who had left their homeland, by force or by choice, and settled in Sicily, in Ortigia, only to be uprooted again generations later.

I slept soundly that night in my room at Amalia’s boutique hotel, four flights and sixty feet above the ancient Mikveh, surrounded by the old walls and alleys of Ortigia’s Guidecca. I tried to imagine what it had all been like before the Inquisition, but I kept getting brought back to the present and being mesmerized by the endless expansiveness of the aquamarine and turquoise waters of the Ionian Sea. I got lost in enjoying the colors of fruits and spices in the marketplace and exploring the narrow streets with all varieties of plants and flowers and the winding boulevards that led me around this ancient island of art and history.

****

The building that Amalia Daniele bought in 1986 is now a boutique hotel with a small museum featuring the collection of broken pottery and vessels that she found at the bottom of the mud-filled Mikveh. She has written several books about her discovery and research, and she plans to add more information to the museum in the years to come.

Without the important discoveries by Amalia, this history could have remained hidden forever. She has helped to bring more knowledge and understanding of the Jewish history of Ortigia by her discovery of the ancient Mikveh, the Bagno Ebraico.

I dedicate this article to my friend of many years, Judith Zorzy, who shares my love of Italy and who introduced us to the splendors and beauty of Sicily.

Lena S. Keslin is an artist and writer in Santa Fe. This story is the fourth of her now nationally award-winning special series, Hidden in Plain Sight, springing from her many travels exploring the Jewish heritage of Europe, which began with the Fall, 2024 issue of the New Mexico Jewish Journal:

* Hidden In Plain Sight, Amsterdam (2nd Pl. NM Press Women, 2025)

* Hidden in Plain Sight, The Old Jewish Cemetery on the Lido, one of the many islands of Venice, Italy (reprinted in HaLapid, Society of Crypto-Judaic Studies. Awarded: 1st Place, NM Press Women; 2nd place, National Federation Press Women 2025, for Photographer/Writer, as published in the NMJJ).

* Hidden in Plain Sight, The Alhambra in Granada, Spain (reprinted in SAJAC Journal, South African Jewish American Community in San Diego).

* Hidden in Plain Sight, Unearthing the Subterranean Mikveh of Ortigia, Sicily.

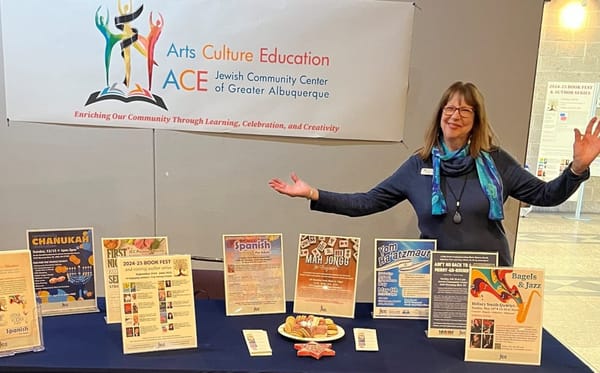

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.