My Relationship Wasn’t Great, But His Father Changed My Life

By Judith Fein

“Look,” I said to a woman who invited me to a party in Switzerland half an hour away from where I lived, “I’d love to come but I just broke up a long-term relationship and I don’t have a car right now.” “I really want you be there.”

“How about this? I’ll come if one of your other guests can drive me.”

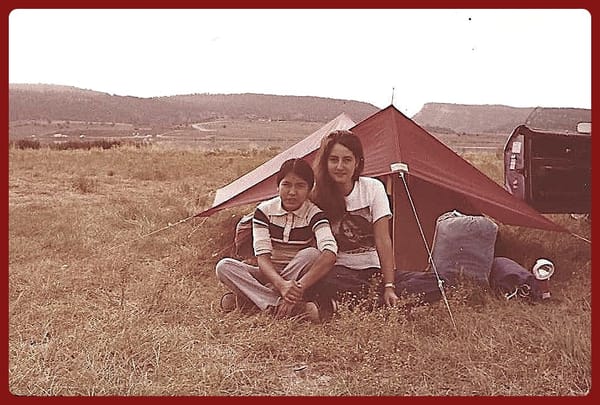

His name was Rami. He was short, dark, handsome, smart, quirky, and intense. He drove me to the party and seemed amused by what I did there. If you’ve ever ended a long-term relationship, you know that sleeping can be an issue. Your life has just changed, and your emotions always want to be sorted out in the middle of the night. I calculated that I had slept a grand total of eight hours in the previous week.

So, after greeting the hostess, I grabbed a designer pillow, lay down on the white Berber carpet in her living room, and promptly fell asleep. When I next opened my eyes, the party was over, Rami had been watching me sleep, and he drove me home. He already had my phone number, he called, and next thing I knew, we were in a relationship.

It was in the mid ‘70s and things were tense between Israel, its Arab neighbors, and Palestinians living in Israel. Rami’s lineage was Middle Eastern Arab. Mine was Eastern European Ashkenazi. Rami was in business school, I was running a theatre troupe, and we had innumerable things past and present to talk about, so our differing religious and cultural origins weren’t a dominating issue in our lives.

Rami invited me to his house, where I met his siblings. And his parents. His mother Dina was reputed to have been the most beautiful woman in West Africa when she and her husband lived there. His father Amir was an important man in his home country. The family was living in Switzerland because Amir had a stroke, he needed excellent medical care, and was largely confined and comfortable in a large, thickly upholstered armchair. His speech was terse and deliberate, and he walked with a slow, uneven gait.

From the first time I entered his house, I felt at home. Culturally-based food was very important. Dina was a skilled cook. The wooden dining room table had several extra leaves, and there were frequently guests. Conversation was fast, funny, and intelligent. It could easily have been a Jewish household in New York, where I grew up.

But it wasn’t. It was an Arab household where other Arabs came to consult with Amir. He never used the first person “I” when he spoke. It was always “we.” Because of the verbal limitations of his stroke, he was verbally direct, forceful, and always very present.

Rami mentioned that his sister’s boyfriend was an Egyptian Jew, and not allowed in the house. “Does your dad know I’m Jewish too?” I asked Rami. “Absolutely not.”

After we had been dating for a while, I had to return to the USA to see my family in California and Rami decided to accompany me. I had told my family in advance that he was Arab. Their icy silence spoke loudly. Their first comment about him after our arrival was, “We thought he would look like Omar Sharif, not Sirhan Sirhan (the man who killed Robert Kennedy).” I am sure you understand that their reaction sort of killed further conversation.

When we walked along the ocean, a few people told Rami to “go back to where you came from.”

And then there was the matter of the seder. It was at my mother’s house, and she had been cooking for days. The table was impeccably set with her expensive dishes, matzo was piled up on a special plate, and Rami seemed quite interested. Until we came to the part where we dipped our pinkies in red wine and made dots on a plate to signify each of the ten plagues. And part of it was the killing, by God, of the Egyptian first-born babies. Followed by songs.

I wanted the floor to part like the Red Sea and swallow me, so I didn’t have to see the look I imagined in Rami’s eyes.

My relationship with Rami was “complicated” as folks say now on social media. But back then it turned out to be fraught and painful for me. It had nothing to do with our different backgrounds but, rather, it became apparent over time that he had a cold and unfeeling side to him and he needed to maintain control. Why did I stay with him? Maybe I hadn’t yet processed my childhood and was repeating it. Or it’s that I was connected to his family and friends. I never tired of asking questions and learning about them. And one thing was certain: my special relationship with his father Amir sustained me. That and lobster.

In retrospect, I think Amir was sweet on me, and he knew that I was sweet on that delicious red crustacean. Once a week, I would get a call from Amir which consisted of two words: “Judie, lobster.” I always replied excitedly, “Yes!”

Each time, a cab arrived in front of my apartment house door, with Amir and Rami inside. It whisked us off to an expensive restaurant where we were outfitted with lobster bibs and had delicate forks to lift the meat from the shell.

One of these particular evenings, as the three of us were consuming our ocean delicacy, Rami posed a seemingly-innocent question of his father.

“Hey, dad, you know those funny Woody Allen movies with all those neurotic New York Jews?” Amir nodded yes.

“Well,” Rami continued, “Judie is one of them.”

Amir didn’t have one moment of diner’s hesitation. He put down a claw he had just finished emptying, gathered a forkful of fluffy white rice, and continued his meal. I kept looking straight ahead while my eyes darted over to catch Rami’s. His orbs looked back at mine, but nothing other than normal dinner conversation followed.

Every day after that, I grilled Rami. “Did he say anything?” “No.” “Not even a few words?” “Nothing.” “Did he say something bad about me?” “Nope.” A week passed like this. I was so on edge that if I were a crustacean I would have leapt out of my shell.

Finally, Rami said his family wanted me to come for dinner. “Uh-oh,” I thought. “Here it comes.”

When I arrived, there were multiple visitors in the living room. I shook hands and greeted each of them, exchanged friendly conversation with all the family members, and flashed a rictus smile at Amir. He nodded. Acting and theatre were my life then, so I played normal. But I assure you my heart was racing like a Porsche.

After what seemed like eons but was probably an hour of pre-dinner drinks and convo, Amir announced, “Dinner!” Everyone stood up and transferred to the dining room. As I looked around for an empty seat at the table, Amir commanded in a booming bark, “Judie, here!” And he pointed to a chair at the end of the table, opposite the place at the head of the table where he always sat.

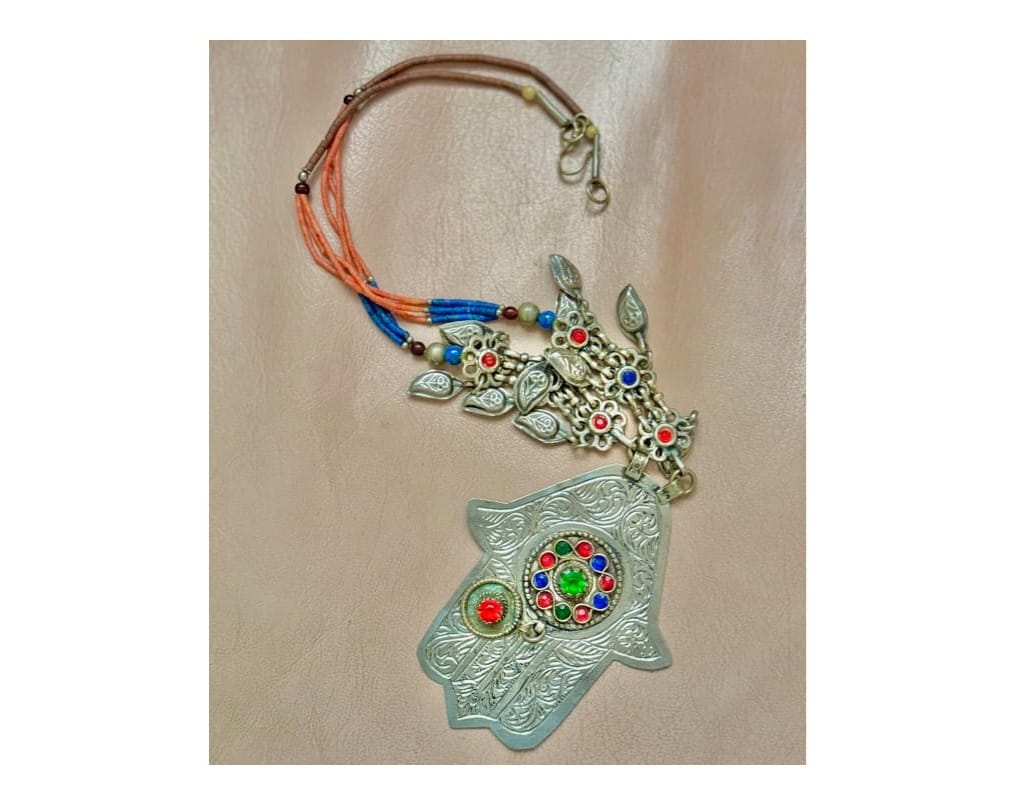

All conversation stopped. I felt I was on emotional death row, and this was my final meal. I sat down. Amir shuffled to his chair. All eyes were on him, and silence filled the room. Amir loudly spoke my name. “Judie!” he bellowed before pointing to the organ in the middle of his face. “Your nose, my nose, no difference.”

Everyone at the table looked from Amir to me, and from me back to Amir. He smiled and, simultaneously, so did I. There was a brief pause, when no one spoke. Pita was passed and the meal began.

At that moment, Amir affirmed something that had always been important to me, and that I often got in trouble for when I was growing up. I wasn’t satisfied with being exclusively with people who shared my background, beliefs, and ways of looking at the world. I was attracted to people who came from other backgrounds, cultures, countries, and religions that were not the same as my own. Sometimes they were at odds with my people. I never hid my own origins and never tired of asking about theirs. For the first time in my life Amir made this okay.

It enabled me to travel and live in other countries, to become a travel journalist, to have diverse friends, and to remember Amir and thank him for his acceptance.

It was always, and always will be true for me. Their nose. My nose. Your nose. No difference.

(Note to the reader: I have changed the names in the story. Amir and Dina passed years ago. I am still in touch with Rami and his remaining family. My bashert husband met Rami’s brother about 7 years ago and they immediately connected. Their noses are similar.)

Judith Fein and Paul Ross have contributed articles and photos to more than 130 international publications, and are author/photographer for the recently released, award-winning experiential travel book SLOW TRAVEL NEW MEXICO: Unforgettable Personal Experiences in the Land of Enchantment. Judith is a popular speaker, opera librettist, playwright, former Hollywood screenwriter, and author of the books LIFE IS A TRIP; THE SPOON FROM MINKOWITZ; and HOW TO COMMUNICATE WITH THE DEAD. One of her stories was the #1 most read article in the New Mexico Jewish Journal, and she is proud of that. Paul also performs as PJ, a highly entertaining cowboy poet who has recently added a kosher cowboy poem to his repertoire. For information about the duo’s upcoming talks and events: https://www.Globaladventure.us

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

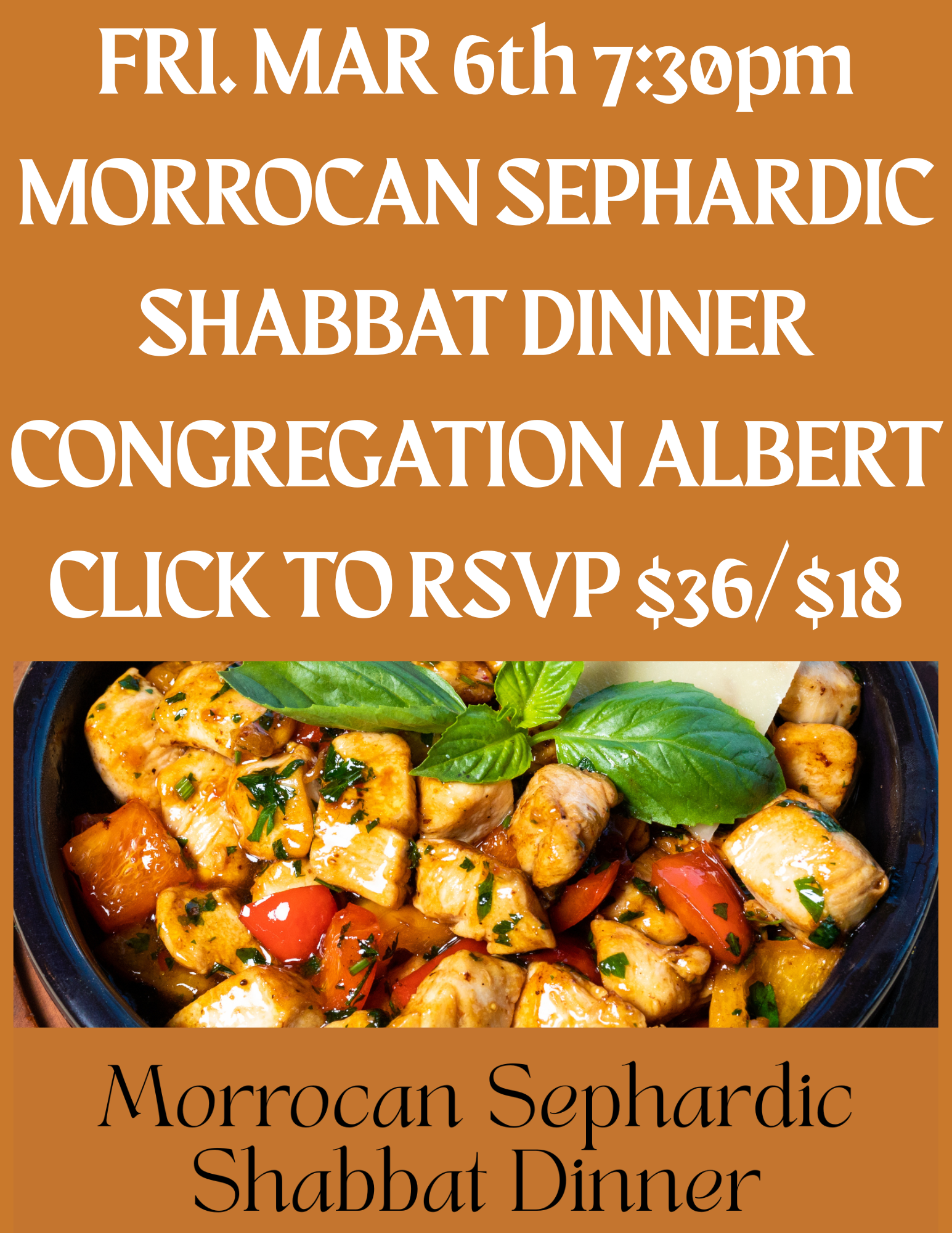

Congregation Albert

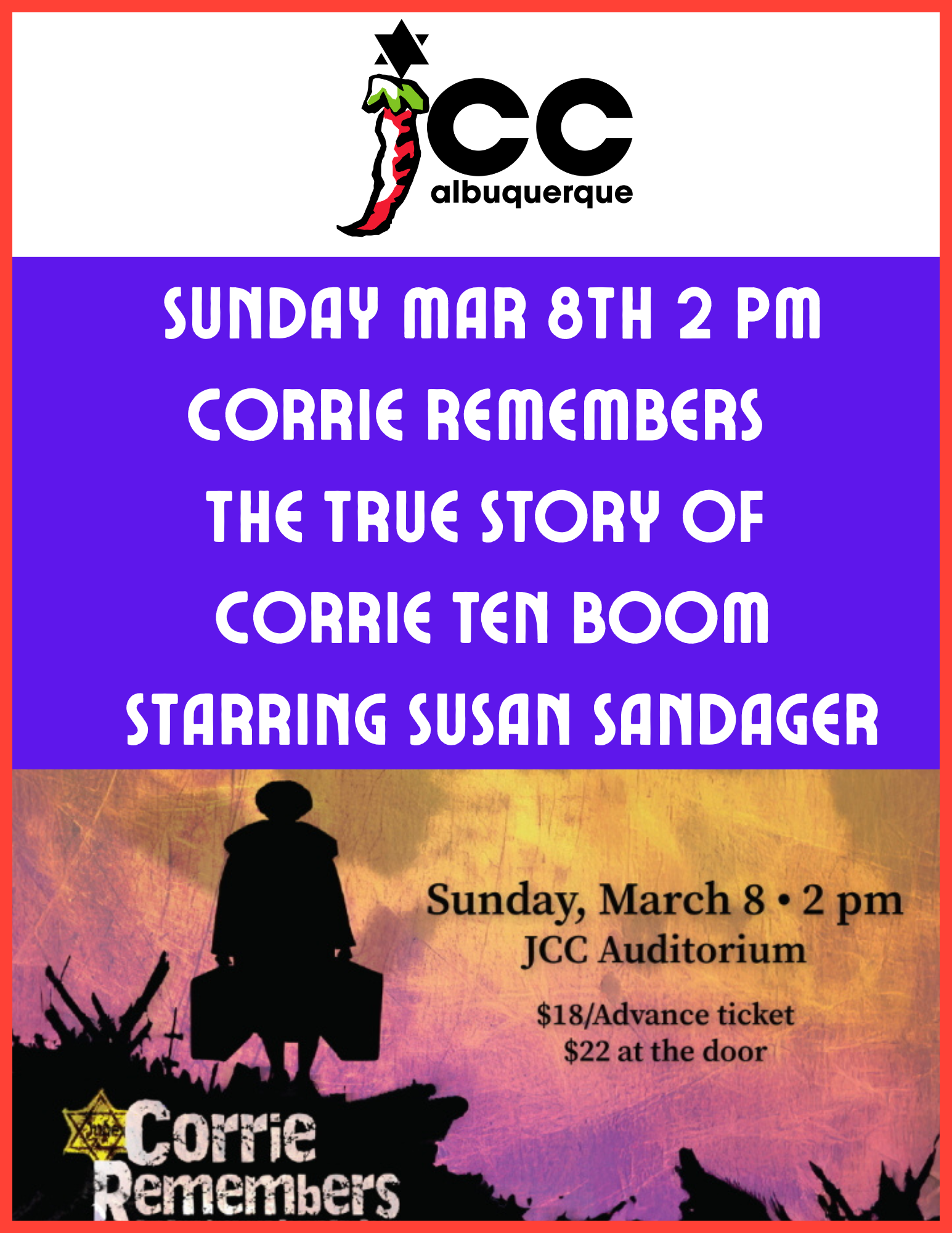

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

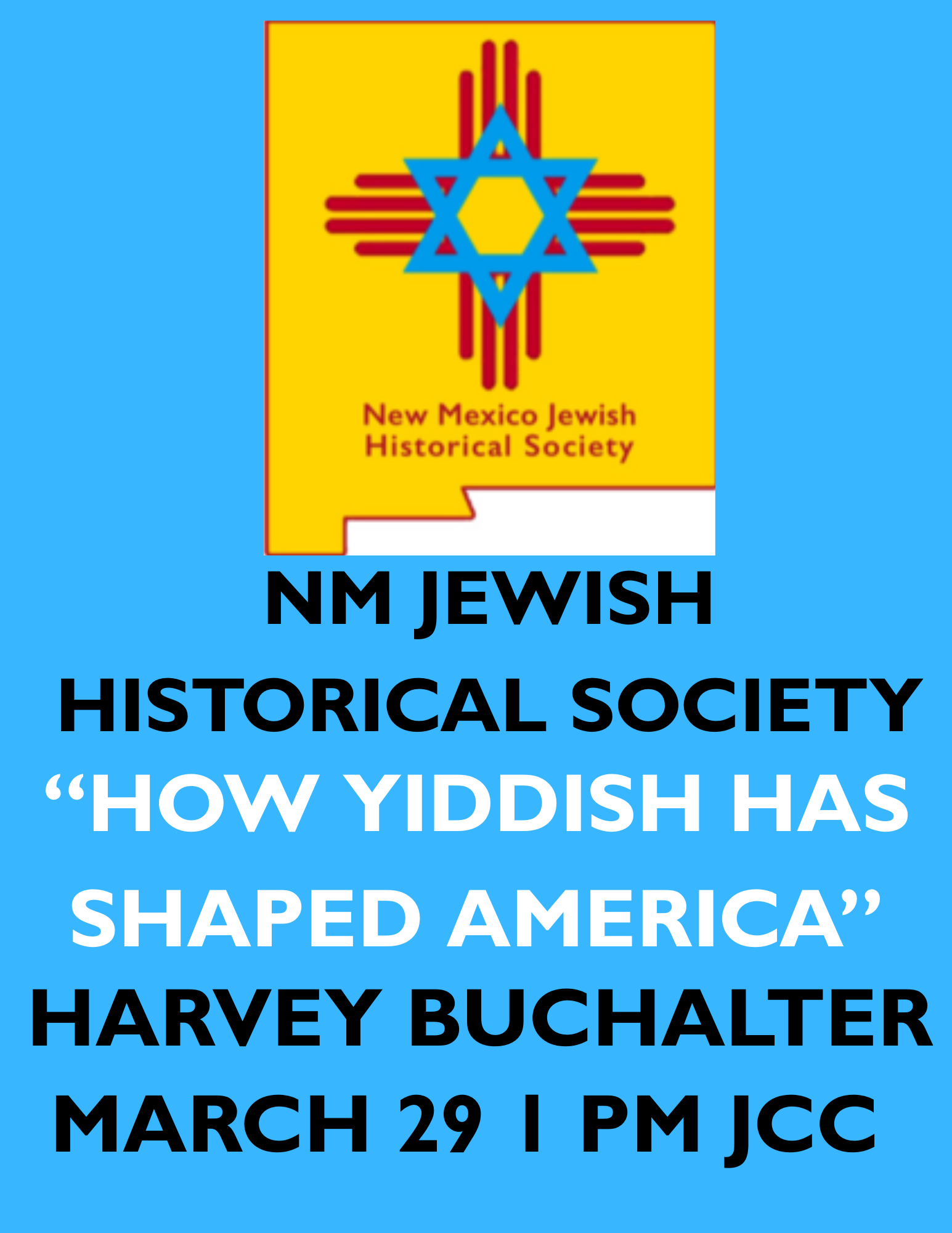

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

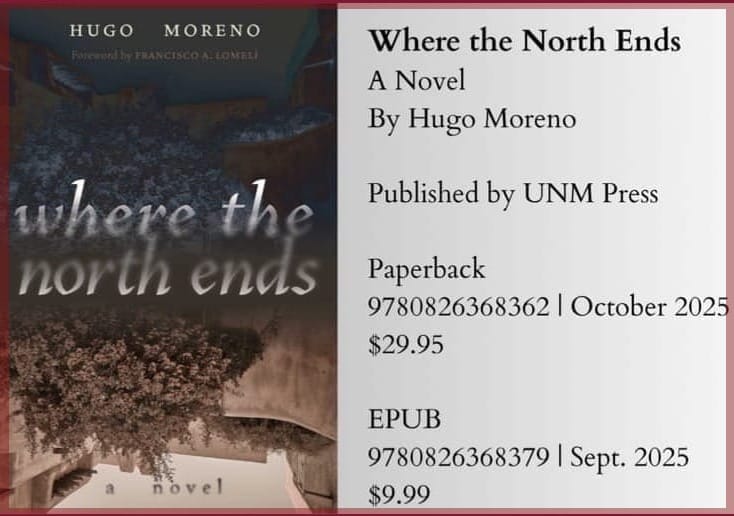

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2026 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.