Rachel Cockerell’s Melting Point: The Galveston Movement of 1907-1914

by Dianne R. Layden, Ph.D.

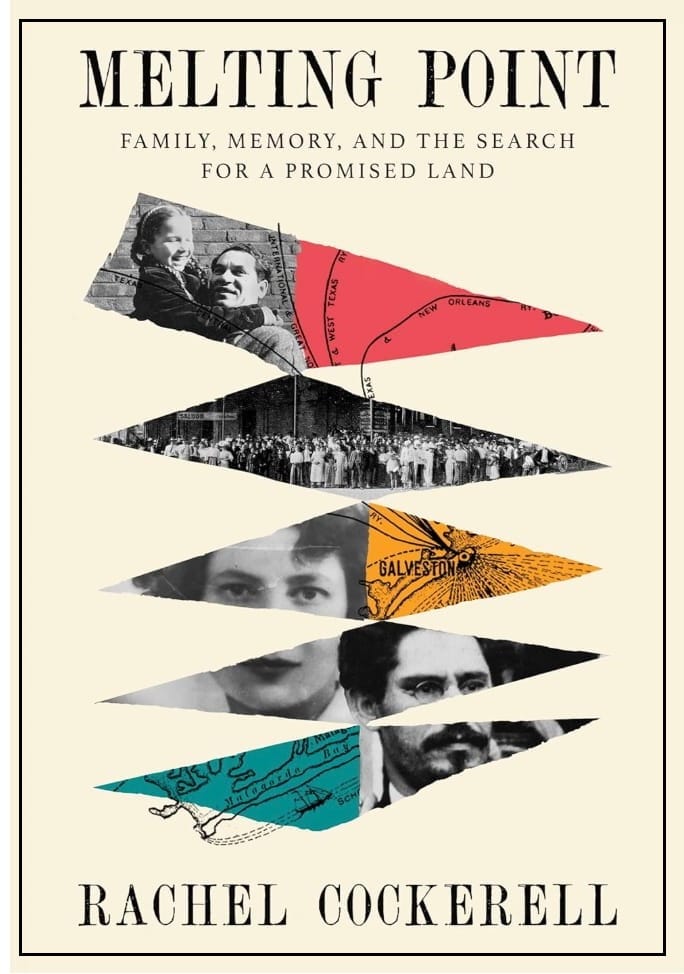

In her remarkable first book, Melting Point: Family, Memory, and the Search for a Promised Land, Rachel Cockerell presents history and memoir in an experimental format in which original source material, with all its nuances, is presented as historical context – the search in the early 1900s for a Jewish homeland outside Palestine, to avoid regional conflict; the Galveston Movement, which relocated 10,000 Russian Jews to the United States through Galveston, Texas; and the movement’s enduring influence on Cockerell’s family, from her great-grandfather, movement leader David Jochelmann, to his son and granddaughter in New York, to his daughters’ families in England, including great-granddaughter Rachel.

Several notable figures played important roles. Theodore Herzl, Viennese journalist, lawyer, and activist who founded modern Zionism, led the search for a homeland with a focus on Palestine. Herzl chaired six Zionist Congresses in 1897-1903 and died in 1904. The Congress later ended the focus on Palestine. Zionist Israel Zangwill, celebrated British author and playwright and, the “most famous Jewish figure in the English-speaking world at the turn of the century," (Cockerell 4)1 , who formed and led the Jewish Territorial Organization. Zangwill wrote, “If we cannot get the Holy Land, we can make another land holy.” The search “looked beyond Palestine to Kenya (mistakenly identified at the time as Uganda), Australia, Canada, Mexico and many other places,” all deemed unsuitable.

David Jochelmann was head of the Russian emigration bureau, whom Zangwill credited for his “brilliant guidance.” David traveled from shtetl to shtetl to recruit emigrants. When he died at 73 in 1941, the New York Times noted that his name was a household word in Jewish homes throughout Eastern Europe. Other leaders included benefactor Jacob Schiff 2 and Rabbi Henry Cohen in Galveston, Zangwill’s friend and the “rabbi of Texas.”

Cockerell’s format provides multiple perspectives on people and historical events with timely quotations from diaries, letters, interviews, newspapers, and magazines. Her well-organized and well-documented storytelling through original sources moves the narrative from the 1890s through the 1940s. Here is a sample entry by Chaim Weizmann, a president of the World Zionist Organization and first president of Israel:

“’The personality of Herzl grew not only in the eyes of those who came into direct contact with him but also in those of people who never saw him. He became a monumental, mythical Jewish figure – something of a legend. Herzl’s . . . message was soon passed on to every town, great or small, in Poland and Russia in which a Jewish ghetto existed.’”

Between 1880 and 1924, when the U.S. Congress severely restricted immigration, as many as three million Russian Jews migrated to the U.S. (Library). One impetus was waves of pogroms in the Russian Empire – notably in 1880-1882, 1903-1906, and 1917-1919 – with tens of thousands of Jews murdered, villages and homes destroyed, women raped, and property looted. Economic privation and oppressive anti-Semitic laws also were factors.

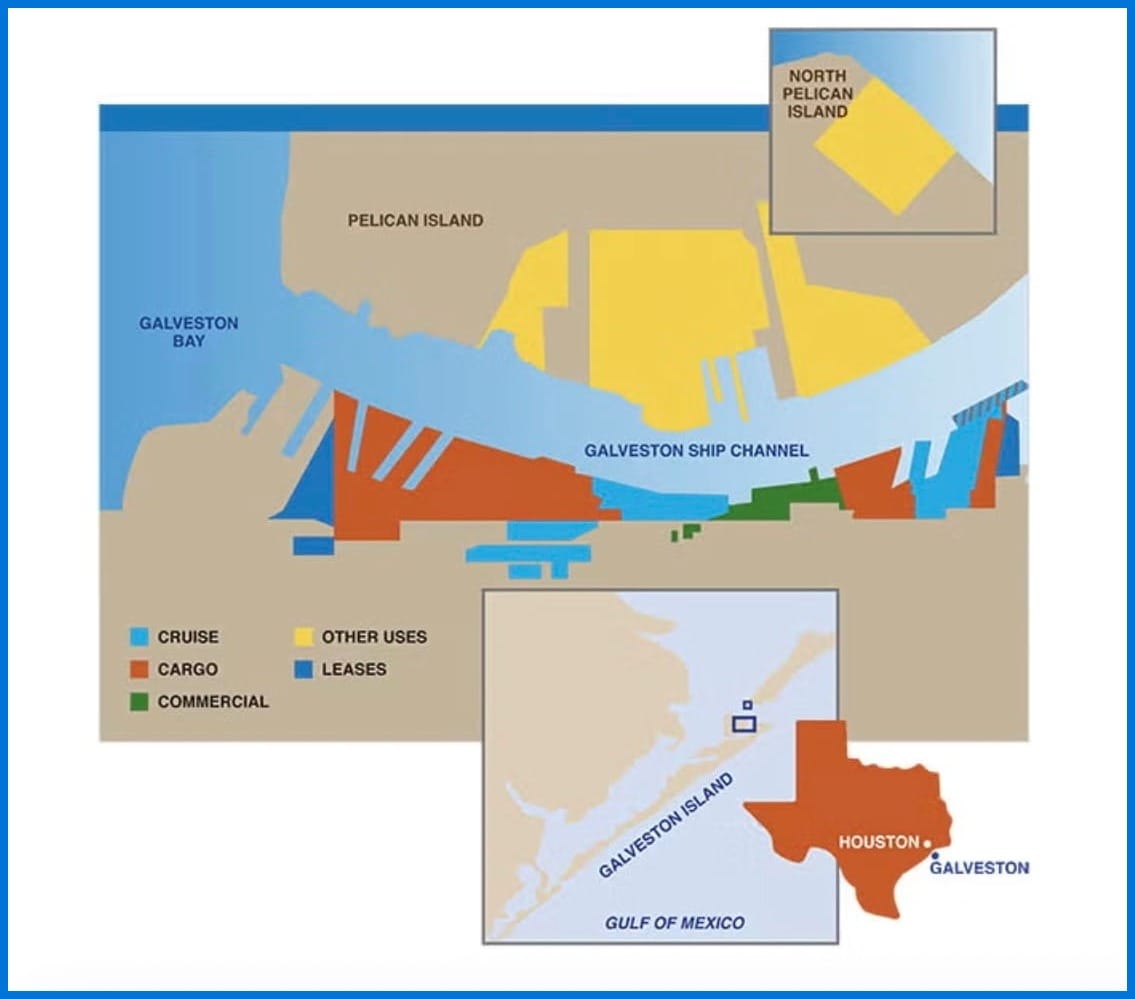

Port of Galveston. Galveston is an island in the Gulf of Mexico off the mainland of southeast Texas about 50 miles from Houston, connected by a causeway over Galveston Bay. Galveston is named for Spanish military and political leader Bernardo de Galvez (1746-1786). A devastating hurricane in September 1900 destroyed the city and caused 6,000-12,000 deaths, the deadliest hurricane in U.S. history. The Port of Galveston was created in 1825 by Mexico, following independence from Spain in 1821, and became a major port in the nineteenth century: “Between 1839 and 1920, the Port of Galveston admitted 750,000 immigrants from around the world” (Searle),4 including 10,000 Russian Jews in 1907-1914, who traveled by train inland to cities across the U.S. Emigration ended with the outbreak of World War I.

Melting Point is composed of three parts: Part One: “Vienna, Basel, Galveston” is about Zionism and the Galveston Movement. Part Two: “New York” and Part Three: “London” are primarily about Cockerell’s family – David Jochelmann and his children and grandchildren with first wife Rivka and second wife Tamara.

Part Two tells of David’s son Emmanuel with Rivka, born in 1898 and Cockerell’s great-uncle. His father brought him to New York in 1912, where he was then alone: “‘For his father remained in this country but a short time before returning to continue his work of Jewish colonization as an escape from the pogroms of czarist Russia’” (Cockerell 182-183, citing Sender Garlin, New York Daily Worker, 1927). Readers aren’t told about Rivka and David’s other two children.

Emmanuel changed his first name to Emjo, combining letters from his first and last names, and changed his last name to Basshe, a maternal family name. In the 1920s, he became a playwright of some note. He attracted a wealthy patron, Otto Kahn, and joined a group of experimental playwrights that included acclaimed novelist John Dos Passos. The New Playwrights Theatre operated in 1927-1929, until low attendance prompted Kahn to withdraw support.

Emjo married Doris Troutman in 1929, and daughter Emjo II was born in 1930, later called Jo. Melting Point is dedicated to Jo, whom Cockerell tracked down in Canada and befriended. Her narratives are a highlight of the book. Her father died at 40 in 1939. Jo writes of never having gotten over his death, dreaming of him, and missing all the years she didn’t have him: “‘He’s almost always somewhere in my mind.’”

Part Three, set in London, describes the advent of World War II and the lives of David’s daughters with Tamara – Fanny and Sonia – and their families.

Fanny, an Anglophile, married a British gentile, Hugh Cockerell; their children are Michael, David, Lolly, and Victor. Michael is Rachel’s father. In contrast, Sonia married a Russian immigrant and Zionist, Yehuda Benari, called Leva; their children are Mimi, Judy, and Dan. According to Mimi, by the time Judy came along, “Mum insisted she had to have a Jewish name that was acceptable in England, so they chose Judith.”

They all lived in a huge house in North London in the 1940s. Leva worked for Vladimir Jabotinsky, a passionate Zionist and founder of the Revisionist movement that sought full territorial control of Palestine. After Adolf Hitler rose to lead Germany in 1933, Jabotinsky argued for mass evacuation of European Jews to avoid catastrophe. Leva was sent to Poland in 1938 to tell Jews to leave.

The narrative shifts to family life. Fanny’s son Michael describes his home as “‘a bit of a madhouse. There were always people up and down the stairs, and in the garden, and playing ping-pong. Always things happening, almost always my mother in a rush to do something or other.’” Sonia’s daughter Mimi averred, “‘I think the Cockerell kids wished that my mum was their mum, whereas we all wished that Fanny was our mum. Sonia was caring and loving, and if you fell over she comforted you, whereas Fanny used to go to the park and play cricket with the kids.’” Other relatives were welcomed. Jo, Emjo’s daughter, traveled to England to meet her British kin, all descendants of their grandfather David.

Cockerell devotes a chapter to formation of the State of Israel in 1948 amidst great controversy. British rule of Palestine, dating from World War I, “favoured ‘the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people.’ The Mandate also said that the rights of non-Jews must be protected,” citing the Sunday Mirror. Cockerell quotes observers who recognized the needs of hundreds of thousands of displaced European Jews after World War II and the irreconcilable Arab and Zionist demands for a homeland, which continue today.

But Sonia, Leva, and their children at last found their long-sought homeland when they moved to Israel in 1951, a most satisfying conclusion. Sonia missed Fanny, but they didn’t return to England.

In a published interview, Cockerell explains the title Melting Point as the moment when a person assimilates: “‘I don’t know when Judaism started to fade away from my family . . . I definitely feel more Jewish than when I started writing the book, discovering this path that could so easily been forgotten . . . That was really powerful for me, but it has made me more aware of how much has been lost.’”

Dianne R. Layden, Ph.D. is a semi-retired professor and writer in Albuquerque. Her field is American Studies. She published a booklet in 2024 about historic Temple Montefiore in Las Vegas, NM, which is available on the New Mexico Jewish Historical website, NMJHS.org. Dr. Layden won a national award for her 2017 article in Legacy, the NMJHS newsletter, about New Mexico Holocaust survivors. In 2022-2025, she portrayed Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg for the New Mexico Humanities Council.

Also by Dianne Layden: Tribute to Frances Levine’s New Book, Crossings: Women on the Santa Fe Trail and Etty and the Etty Project: Susan Stein in New Mexico.

Notes

1Zangwill coined the term “melting pot,” the title of his 1908 play about a Russian immigrant family in the U.S.

2In suggesting what came to be known as the Galveston Movement, Schiff told Zangwill he worried about the mounting congestion of Jewish immigrants in New York City. Other cities considered and rejected were Baltimore, Charleston, Savannah, San Franciso, and New Orleans.

3United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Holocaust Encyclopedia: Pogroms,” n,d., https:// encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/pogroms. “Pogrom is a Russian word meaning ‘to wreak havoc, to demolish violently.’ Historically, the term refers to violent attacks by local non-Jewish populations on Jews in the Russian Empire and in other countries.” Between 1881 and 1920, 1,326 pogroms in Ukraine took the lives of 70,000-250,000 civilian Jews, leaving half a million homeless (“Pogrom”).

4Readers may know the story of Sam Ravel, a Russian immigrant who arrived in Galveston in 1905, before the Galveston Movement. He moved to Columbus, New Mexico in 1910, where his businesses included a general store that sold firearms and ammunition. In 1916, Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa raided Columbus, perhaps to kill Ravel over a sale that Villa perceived as wrongful. The death toll was nine local military officers, 10 civilians, and about 78 Villistas (Abarbanel). Ravel was safe in El Paso that day. Stacey Ravel Abarbanel, Sam’s granddaughter, tells the story in her award-winning documentary film, UnRaveling (unravelingdoc.com). “The true answer seems lost to time, but the fact that it was Ravel Villa’s men were looking for is unquestioned . . . Abarbanel was never able to lock down the reason for Villa’s animus toward Ravel . . .” (Teicholz).

References

Abarbanel, Stacey Ravel. “Pancho Villa and My Grandfather,” Tablet Magazine, August 26, 2019, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/community/articles/pancho-villa-and-my-grandfather.

Cockerell, Rachel. Melting Point: Family, Memory, and the Search for a Promised Land. Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2024.

Joseph, Anne. “How I told my family’s history through the words of early Zionists.” The Jewish Chronicle, February 28, 2024, https://www.thejc.com/life/i-definitely-feel-more-jewish-than-when-i-started-writing-the-book-v1v6dbv4.

Library of Congress. “Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: A People at Risk,” n.d., https:// www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/polish-russian/a-people-at-risk/. Jewish immigrants came to the U.S. “by any possible means, defying the czar’s laws against emigration.”

“Pogrom.” Wikipedia.org, January 28, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pogrom#:~:text= Table_title:%20List%20of%20events%20named%20pogroms%20Table_content:,(1905)%20%7C%20Deaths:%20100%20(Included%20above)%20%7C.

Searle, Madison. “The Story Behind the Song: ‘Galveston.’” Texas Music, November 29, 2023, https:// txmusic.com/galveston/.

Teicholz, Tom. “When Pancho Villa attacked the U.S. in 1916, he was after the head of this Jewish merchant.” The Forward, October 20, 2021, https://forward.com/culture/476934/when-pancho-villa-attacked-the-us-in-1916-sam-ravel-unraveling-abarbanel/.

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

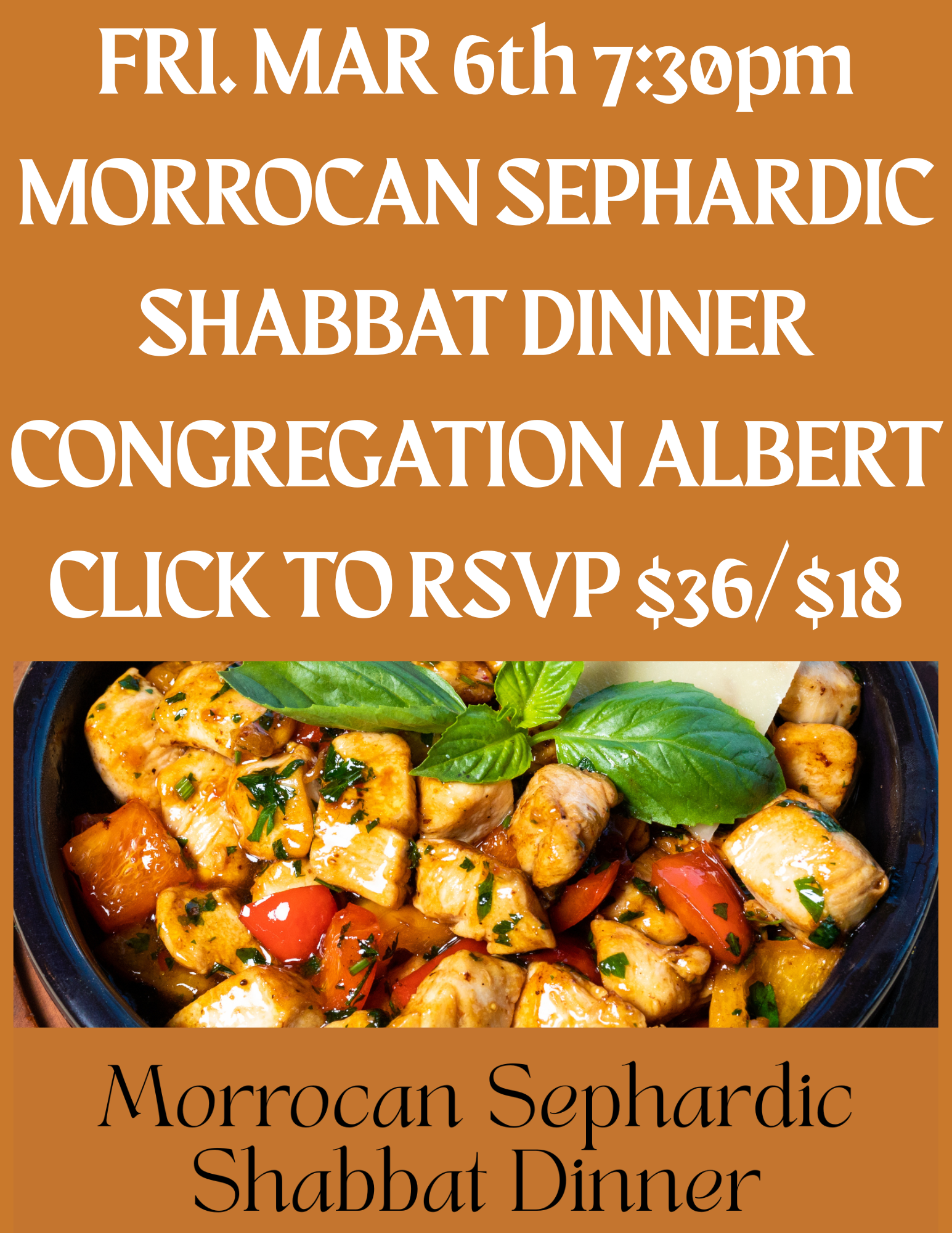

Congregation Albert

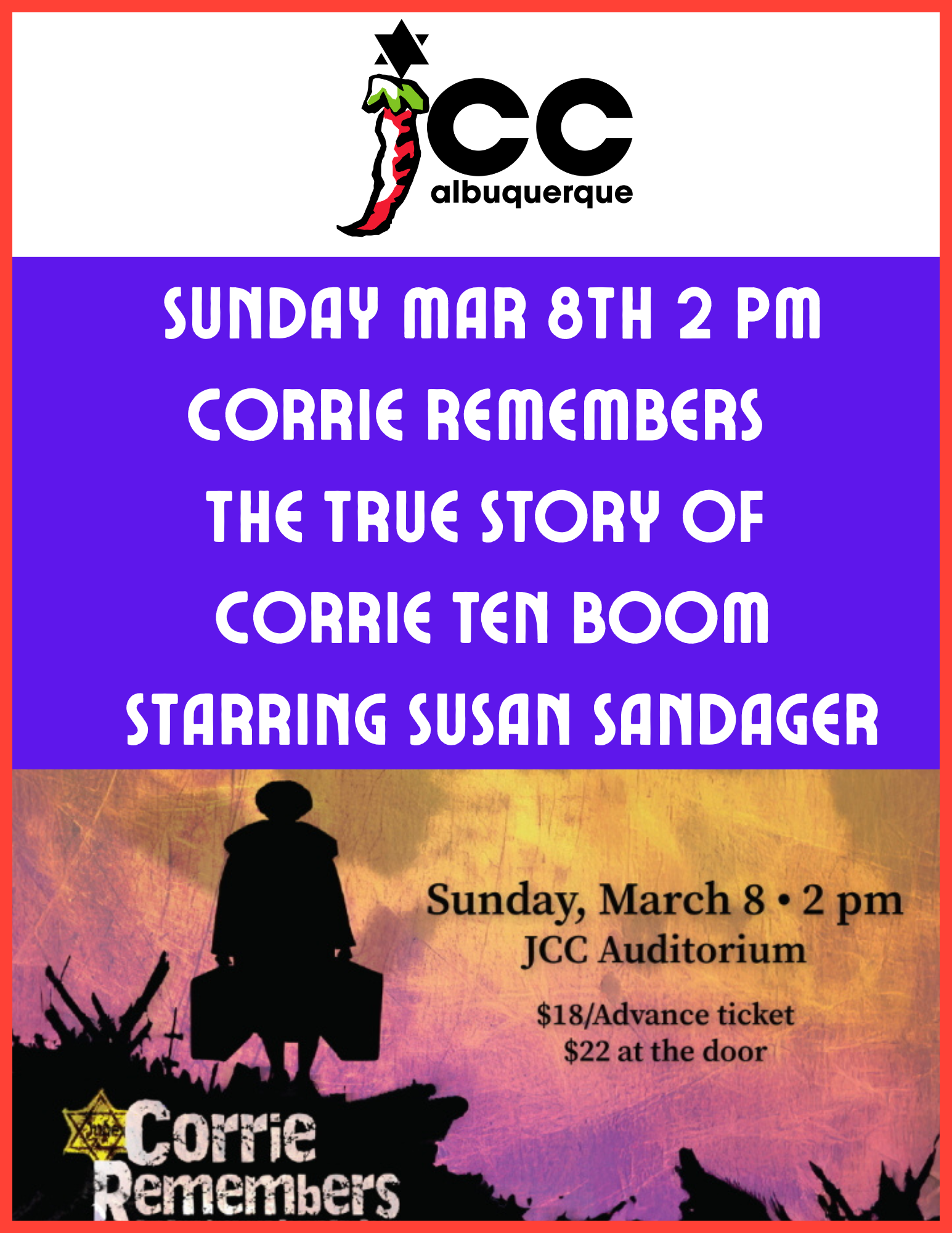

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

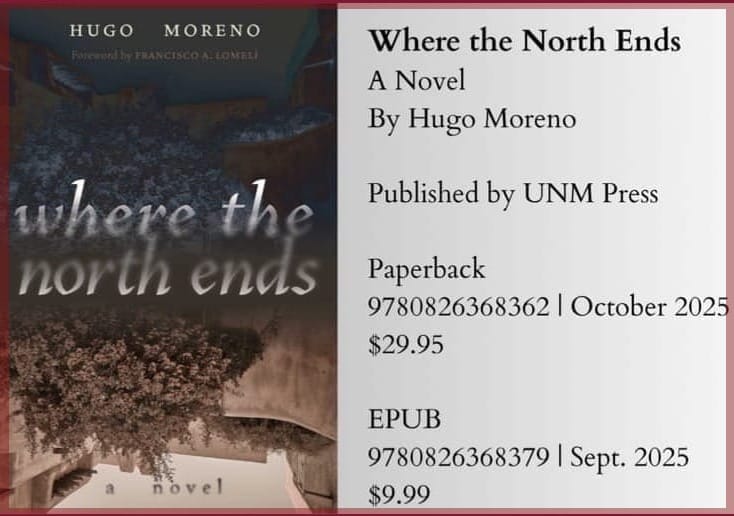

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2026 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.