Tribute to Frances Levine’s New Book, Crossings: Women on the Santa Fe Trail

By Dianne R. Layden, Ph.D.

Dr. Frances Levine is well known in New Mexico for distinguished service as director of the Palace of the Governors/New Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe in 2002-2014. Notably, Levine was one of the moving forces behind the Fractured Faiths exhibit in 2016-2017, about the impact of the Spanish Inquisition on Catholics, Jews, and Conversos whose descendants are the crypto-Jews of today. She also is author of Doña Teresa Confronts the Inquisition and Our Prayers Are in This Place about Pecos Pueblo and co-author of Battles and Massacres on the Southwestern Frontier and Telling New Mexico: A New History.

Levine moved to St. Louis to serve as President and CEO of the Missouri Historical Society and Missouri History Museum in 2014-2022 and then interim director for the opening year of the St. Louis Kaplan Feldman Holocaust Museum, 2022-2023. She holds a B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. in anthropology.

Crossings received the Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá award from the Historical Society of New Mexico for outstanding contribution to Southwest and borderlands history. The book’s title, Crossings, suggests both a sea voyage, taken from contemporaneous descriptions of vast open spaces encountered on the Santa Fe Trail, and the cross-cultural experiences often mentioned by travelers in their journals.

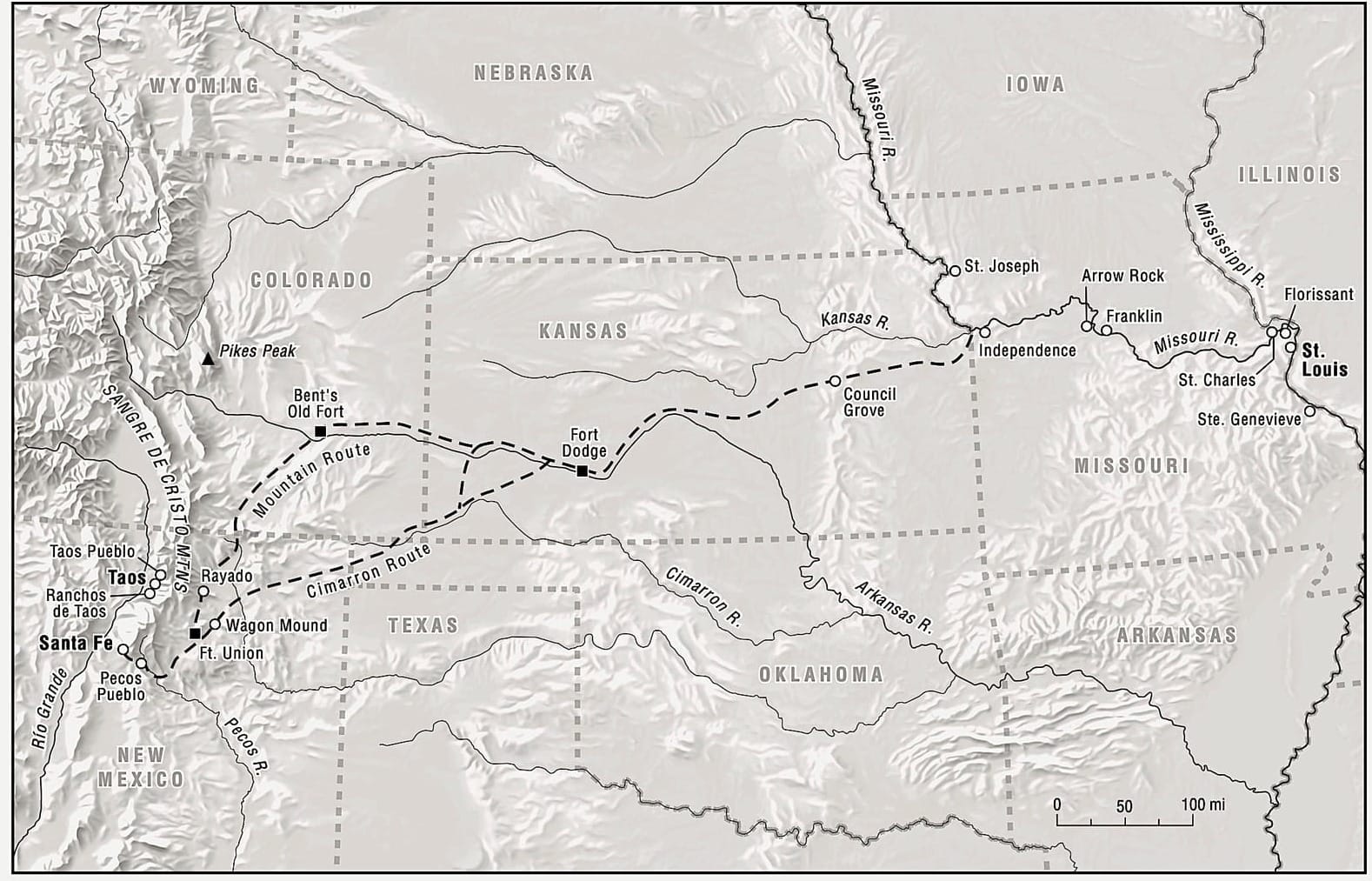

Crossings provides new perspectives on the Santa Fe Trail, which was established for commerce in 1821, when Mexico became independent from Spain (Spain prohibited foreign commerce), for military use in the Mexican War in 1846-1848 and Civil War in the West in the 1860s, and for mail and supply deliveries and travel (see map below). The trail went beyond Santa Fe, which was also the northern terminus of the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (Royal Road to the Interior Land), the historic road to Mexico City that Conquistador Juan de Oñate traveled from Zacatecas, Mexico, to Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo in 1598. The trail also pushed west to California on the Old Spanish Trail.

Women on the Santa Fe Trail

After moving to Missouri, Levine’s research focused on women on the trail, exploring families and communities and the complexity and depth of connections between the Southwest and American Heartland: “Women were central to the western experience and, told through their own words, the story of the Santa Fe Trail is much more than the march of Manifest Destiny and the rise of commercial enterprises” (Levine, ix). For too long, stories of women were ignored or even erased by publishers and scholars, and men were the only sources documenting western experiences. Participation by Native Americans, Hispanics, and African Americans was ignored or erased also.

Levine provides narratives about more than a dozen women, including women of color – traveling east to west, west to east – between 1760, before the trail was named, and the late 1870s, when the railroad arrived in Colorado and New Mexico and supplanted the trail for overland commerce and travel. According to Levine, “The stories of the women in this book are set against this background of conquest, colonialism, commerce, and the larger social consequences of the rapidly expanding United States” (17). Some wrote letters, diaries, or memoirs about their experiences, but few women who traveled the trail are remembered by name. Sadly, “the vast majority of women in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are largely missing from history” (18).

Levine selected women who traveled to, from, or through St. Louis, about 1,000 miles from Santa Fe. In the nineteenth century, when rivers were the highways, Levine argues that St. Louis is central to the trail’s history because the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers near St. Louis “fed goods into and throughout the heart of the continent, making much of the overland trade feasible and sustaining the communities that grew up around it. . . . [T]he goods carried across the Santa Fe Trail influenced every aspect of household and community economies in New Mexico and the West” (174-175). Further, the Santa Fe trade became global.

For most people, travel from Independence or Westport in western Missouri could take 8-10 weeks by wagon train (National Park Service). From St. Louis, Levine said in an interview, the trip could take several days more, depending on the season and other circumstances, e.g., decisions by wagon masters whether wagons would be drawn by mules or oxen, the condition of the grass, the rains, the creeks, the tribal areas, and border wars between Missouri and Kansas (personal communication, July 21, 2025). Dangers on the trail included harsh terrain, extreme weather, and risk of Indian attacks.

Women travelers included Maria Rosa Villalpando, a Hispanic woman from Ranchos de Taos, who was captured by Comanches in 1760, enslaved, and sold twice before she married a French trader and rose in French Creole society in St. Louis. Levine states, “Her captivity and exchange occurred at a time when women and children were trafficked, along with livestock and furs, among Native tribes and with Spanish and French colonists throughout the intermountain West and along the interior rivers” (22).

Carmel Benavides Robidoux, a Hispanic woman born to a prominent Santa Fe family, married a French trader, “one of many cross-cultural marriages, liaisons, and business partnerships between New Mexicans and los extranjeros [foreigners] that developed in the earliest years of the Santa Fe trade” (48). Marriage to Hispanic women granted French and American traders access to social and commercial networks (49).

Three young girls traveled the trail after the death of a parent – Adaline “Prairie Flower” Carson, daughter of frontier explorer Christopher “Kit” Carson and his Arapaho wife Waa-nibe; Francisca “Fanny” Lopez; and Marion Sloan. Some New Mexicans in the mid-nineteenth century sent their children to St. Louis for an education, as New Mexico did not provide public education until 1891. Carson and Lopez were brought to St. Louis by their fathers for a better education.

In New Mexico after 1850, the US military built roads and forts, which provided greater security for travelers. Military wives who traveled on the trail include Anna Maria De Camp Morris, Catherine “Katie” Bowen, Mary Gowan Clarke, and Lydia Spencer Lane.

Other women travelers include Jewish pioneers Bertha “Betty” Seligman Spiegelberg and Florence “Flora” Langerman Spiegelberg; Flora’s diary was first published in 1937. Suffragist and abolitionist Julia Anna Archibald Holmes sought adventure, but her politics were often unreported as writers focused on the fact that she wore bloomers, causing a stir on the trail, and climbed Pike’s Peak. Kate Masservy Kingsbury had tuberculosis and, seeking recovery, left Massachusetts for New Mexico but died on her third crossing of the trail in 1857. Susan Wallace, wife of New Mexico governor Lew Wallace, also traveled on the trail.

The best-known woman traveler probably is Susan Shelby Magoffin, who traveled with her enslaved Black servant Jane and kept a near daily-diary, first published in 1926. Jane is known only by her first name, and information about her – full name, birthplace, age, physical appearance, family circumstances, and how she came to travel the trail – is lacking. What became of Jane is unknown.

Levine devotes a chapter to African American women, noting. “No autobiography or detailed biography of an enslaved women or free women of color has been found in the vast trail literature” (122). Blacks became more prevalent in the literature after the US takeover of the West in 1846, played prominent roles in support of trade, and married into Spanish, Mexican, and Indigenous families. Charlotte Green, the Black cook at Bent’s Fort, a Colorado trading and supply post, was mentioned by trail travelers. Slavery was abolished in 1829 in Mexico and in 1865 in the U.S., although New Mexico, in an unsuccessful bid for statehood, adopted a “Slave Code” in 1859-1862 that briefly restricted Black freedom.

In addition to prejudice against Blacks, as “new American settlers took over the local government and imposed American laws on Hispanic and Native peoples, social displacement and discrimination took hold, even among the Hispanic elites who had held power for generations” (157). Although the trail crossed the traditional lands of at least 10 Native nations, travelers seldom reflected on their incursion on Native land, reduced Native circumstances, or Native removal from homelands.

Importantly, New Mexican women in the US after the Mexican War lost rights to inherited property and earned resources that they held under Mexican law. Under American law, husbands held control of what had been their wives’ separate property.

New Perspectives on the Santa Fe Trail

With abundant references, including notes, bibliography, and index, Frances Levine ably educates readers about women travelers on the Santa Fe Trail from their own stories and stories about them. She also notes the global reach of commerce through the distribution of goods at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, and the relationships among the diverse peoples and cultures that encountered one another. The trail was “an essential conduit of the cultural encounters between expanding US settlements and sovereign neighboring territories and tribal lands” (17). Women as well as men from a mix of cultures settled Missouri and the Southwest – Native American, Black, French, Hispanic, Jewish, and other communities.

References

Levine, Frances. Crossings: Women on the Santa Fe Trail. University Press of Kansas, 2024.

National Park Service, Santa Fe National Historic Trail. “Frequently Asked Questions,” https://www.nps.gov/safe/faqs.htm#.

Dianne Layden is a semi-retired professor and writer in Albuquerque. Her field is American Studies. Her booklet published in 2024 about historic Temple Montefiore in Las Vegas, NM, is available on the New Mexico Jewish Historical website, NMJHS.org. Dr. Layden won a national award for her 2017 article in Legacy, the NMJHS newsletter, about New Mexico Holocaust survivors. In 2022-2025, she portrayed Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg for the New Mexico Humanities Council.

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

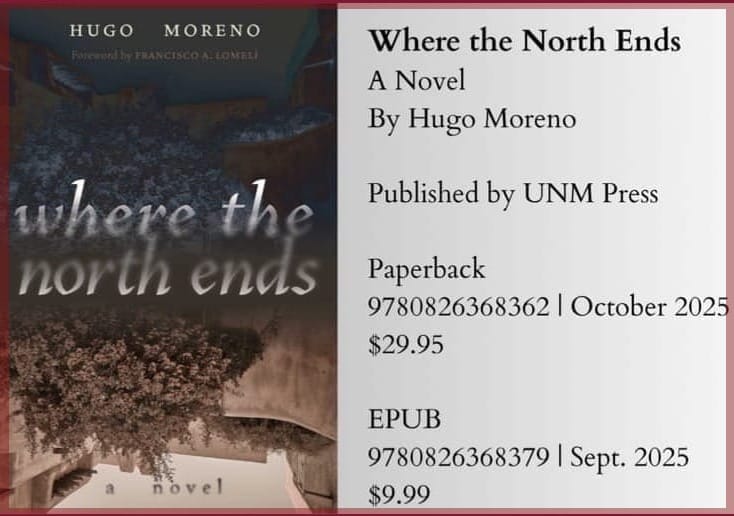

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.