A Dazzling Fashion Show for the Most Famous Jewish Mother in the World

By Judith Fein

Photos by Paul Ross

As an international travel journalist, I have met with prime ministers and presidents. As a Hollywood writer, I had alone time with stars, and heads of studios. Never did I feel a frisson of fear. But I was un petit peu panicky about asking Marcos Gallegos, the mayordomo or official of the cofradia (a brotherhood open to all ages and genders) of the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi in Santa Fe, a straightforward question.

“Is it offensive to you if, in writing, I refer to Mary as ‘the most famous Jewish mother in the world?’”

For a moment, his face was expressionless, but there was an unmistakable twinkle in his eyes. “Why would it be offensive?” he replied. “Jesus was Jewish so of course Mary was his Jewish mother!”

Whew. I mean, really, whew. This exchange took place at a recent show in Santa Fe, called Crown & Cloth: The Sacred Style of Our Lady. (“Our Lady” is the church’s reverent name for Mary, which I use out of respect.) And it was a bona fide fashion extravaganza for the celebrated Jewish mother.

Many years ago, I heard that Mary had an entire wardrobe provided for her by congregants and was told that the clothes were locked away, and couldn’t be seen. My mind sought a Jewish parallel. But, even with our long cultural history of fine tailoring, I had never heard of tuxedos made for Moses, or wedding gowns created for Isaac’s bride Rebecca. That’s probably because, in our tradition, there are no physical statues of them to adorn. I was really curious to see something so rarely shown; the last time Mother Mary’s dresses were on public display was in 2014.

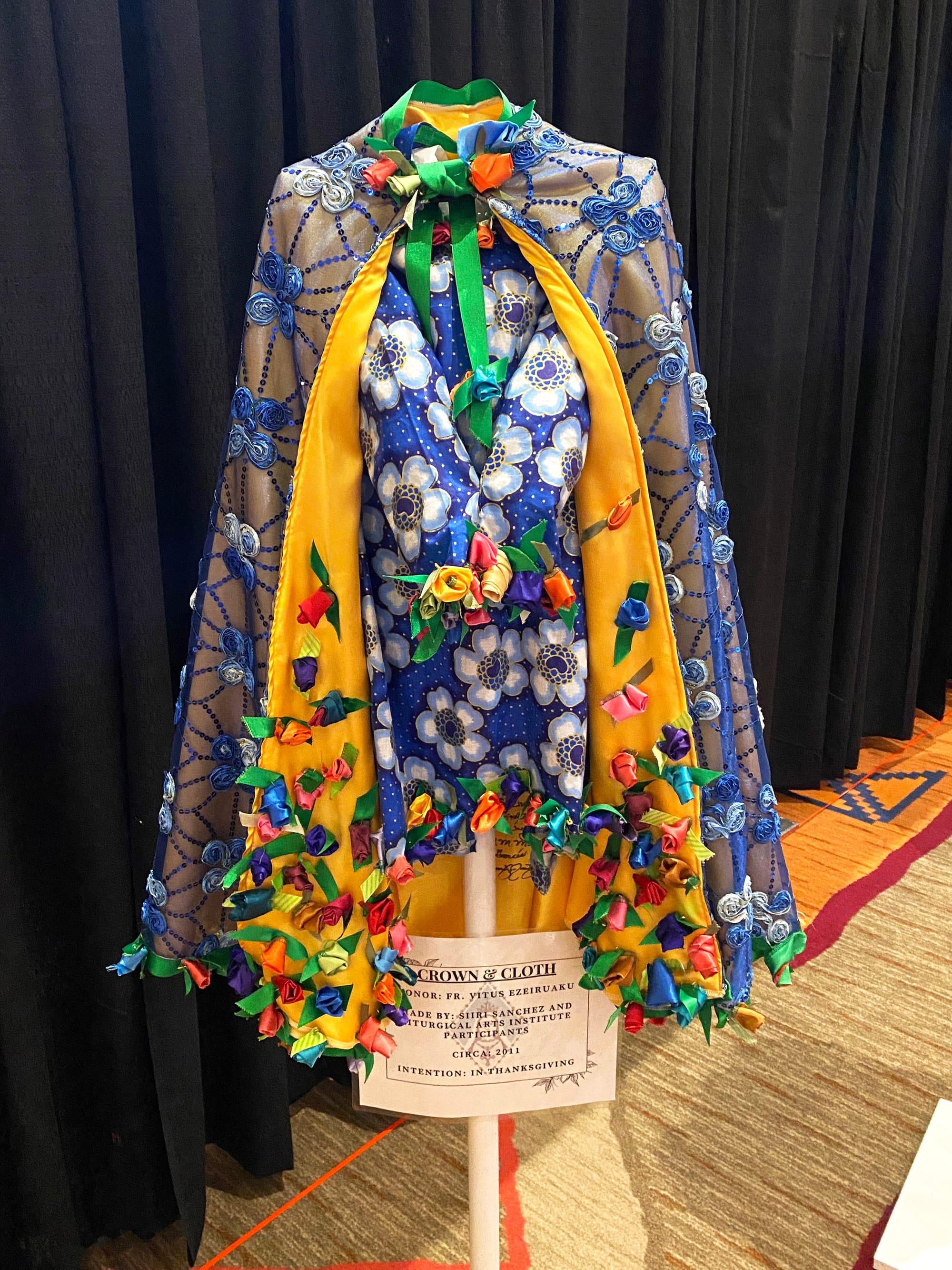

I entered the show at the Convention Center expecting doll-sized clothes, and was startled by 150 sacred gowns, each about half-human size. They were museum quality pieces, in vibrant color, with sequins, painting, embroidery, weaving, applique, fancy stitching, in a range of styles, created from fabrics including silk, satin, chiffon. Some had matching processional capes.

Most of them were offered to the Cathedral in honor of wedding anniversaries, to give thanks for the birth of a child, for restored health, with prayers for peace, in appreciation for the Fiesta in Santa Fe, in memoriam, or with unspecified personal intentions. One section included historical and vintage clothes; another was Native American inspired, a third featured international gowns from China and Korea, and a fourth was in the Spanish Colonial style.

The majority of the dresses were commissioned from talented local tailors and designers. Some, created by the same artisans, were their own personal gifts and offerings. I was delighted to learn that there were not only seamstresses, but seamsters as well, one of whom was in attendance.

Joe Sweeney has created 56 garments over the past decade and 28 of his creations were in the show. His trademarks were appliqué, gemstones, and satin brocade. A gracious, friendly man, Sweeney agreed to answer my questions, which I prefaced by saying I am not Catholic.

“Are people praying to and honoring Mary engaged in a form of goddess worship?” I asked.

“No, we don’t worship Mary,” he explained. “We honor her because at the wedding feast in Cana, she informed her son that the bridal couple had run out of wine.” Wine was essential for the ceremony, and “when Mary called Jesus’s attention to the problem, he transformed water into wine. It was his first miracle.”

Miracles! That is certainly a feat that Jews recognize and honor. Moses parted the Reed Sea. The prophets Elijah and Elisha brought the dead back to life, Daniel survived being thrown in the lions’ den, and Joshua successfully prayed for the sun and moon to stand still so he could lengthen the day and secure victory in battle.

“Then why is Mary honored when it was Jesus who performed the miracle?” I inquired of Sweeney. “Because she intervened with Jesus to make it happen. So, we pray that Mary will intervene on our behalf and our prayers will be answered.”

Sweeney is the new sacristan in charge of the statue of Mary — meaning he will be in charge of all Mary’s clothing and he will do all the dressing. He also helms La Cofradía de La Conquistadora — Our Lady of Peace. He was patient and informed, and made me think about how Jews also pray for intercession. I never understood why the faithful make pilgrimages to the graves of famous, righteous, revered rabbis, and pray to them. “We don’t pray to the rabbis,” an Orthodox rabbi explained to me. “We pray for them to intervene on our behalf and connect us with God, because of their spiritual influence.”

As I walked around the exhibit with Sweeney, admiring his creations, I mentioned that in Catalonia, Spain, I had seen medieval paintings and sculptures of Mary where she was obviously pregnant. We don’t usually see Mary expecting a child, and I asked if there are any contemporary versions of this tradition. “Yes!” Sweeney replied as he stopped in front of a Native American-designed dress with a black belt. “She is Aztec and the black belt is symbolic; it signifies that she is pregnant.”

Sweeney also spoke about another color — blue, or Marian blue, which is associated with Mary. Blue symbolizes purity, faithfulness, the sky and heaven. Mary is sometimes referred to as the “Queen of Heaven.” Color symbolism is in many aspects of Catholic theology and is especially present during the services.

I reflected that in Judaism, color also plays important roles. In the tallit (prayer shawl) and tzitzit (fringes), for example, the colors employed are white and blue. White represents innocence, purity, and connection to the divine. Blue symbolizes nobility and a connection to God.

Central to the exhibit was a separate room. It housed the olive wood statue of Mary, which customarily resides in her own chapel on the north side of the Cathedral and is rarely seen outside of this space. It is the oldest Marian statue in the United States, arriving from Spain in 1625, but was probably made much earlier in the l5th century. The tradition of dressing her like royalty came afterwards, and the infant Jesus in her arms was a later addition. It was in this “inner sanctum” of the exhibit that I met and learned from the mayordomo Marcos Gallegos. It was he who said it was okay to identify Mary as the most famous Jewish mother.

Looking radiant and regal, Mary was protected and guarded on either side by cofradia members, whose role was clearly an honor.

According to Gallegos, the gown she was wearing for the exhibition was a gift on behalf of John C. Wester, the current Archbishop of Santa Fe since 2015. Part of it is made from the vestments he’d worn while a bishop of Salt Lake City, before coming to New Mexico.

Surrounding Our Lady were historic gowns, the oldest of which was created in the 17th century. One of the most notable was a garment made around 1950 from the cloak of Bishop Lamy, the first Archbishop of Santa Fe. The famous 1927 Willa Cather novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop, is based on the story of Lamy, and his life as a Catholic clergyman in New Mexico. (He actually lived in a small house on the property that is now the Bishop’s Lodge resort in Santa Fe. The chapel he built still stands.)

Gallegos had delightful information to share about the legendary clergyman. “The Cathedral here is different from all others, because he wanted it to be European. He didn’t like adobe houses and called them ‘mud huts.’ He didn’t like bultos (homemade wooden statues of saints and other religious figures) and retablos (religious folk art paintings).” It was clear that Lamy was no fan of New Mexico culture and religious folk art, which today draws collectors and admirers from around the world during Santa Fe’s annual Spanish Market.

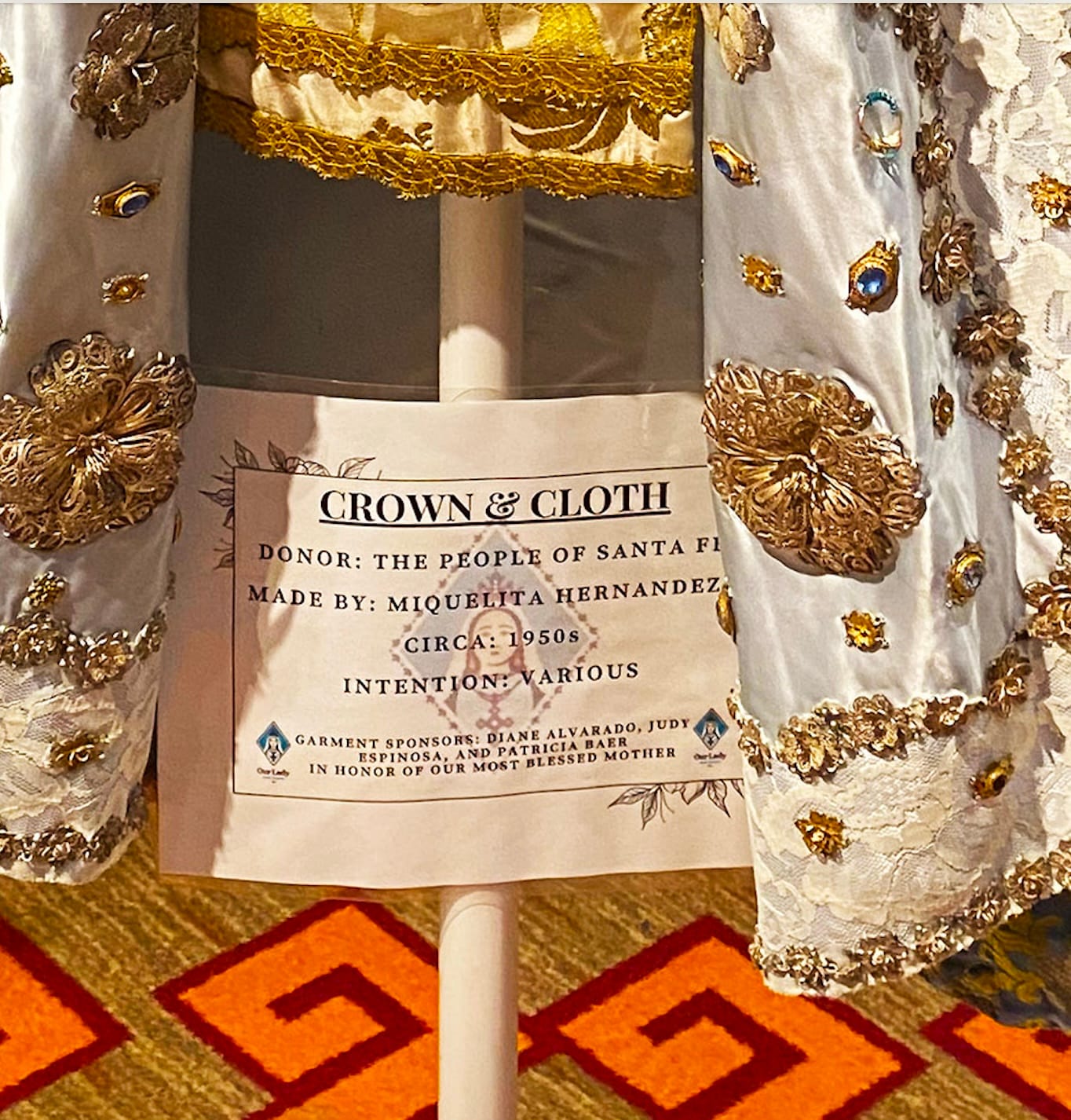

I was fascinated by the sacred items in glass cases in the room with Mary — gold crowns and crosses and a filigree necklace. I admired the historic pieces and then stopped before one ornate garment that was made in the 1950's. In the center, embroidered in gold, was the Tetragrammaton — the four Hebrew letters יהוה that represent the name of God.

The Tetragrammaton, יהוה, Yod Hey Vav Hey, the four Hebrew letters that represent the name of God, is embroidered on this garment. The placard reads Donor: The People of Santa Fe. Made By: Miquelita Hernandez. Circa: 1950s. Intention: Various. Garment Sponsors: Diane Alvarado, Judy Espinosa, and Patricia Barr In Honor of Our Most Blessed Mother. [Editor’s note: If you recognize any of these names let us know] Photos © Paul Ross / nmjewishjournal.com

“Do you know what this is?” I asked Gallegos. “Those are the same letters that are above the front door of the Cathedral.”

Many visitors to Santa Fe are surprised to see the Hebrew letters at the very entry to the monumental basilica. Gallegos certainly knew the most commonly repeated story of how the Hebrew letters got there. “The early parishioners were running out of money for the construction and Jewish merchants provided funds to help them out. This was a way of thanking them.”

Concerning the embroidered Hebrew letters, I explained to Gallegos that when I grew up, I learned you can never pronounce the holy name aloud. All one could do was name the four letters that comprised the name: Yod Hay Vav Hey. It was the holiest name of God, and could never be used. Some Orthodox people replace it with “Hashem,” or “the name,” so as not to pronounce it at all. I also told him that I am in touch with a modern-day Samaritan scholar in Israel who pronounced for me the four letters in their ancient form of Hebrew that was close to Aramaic: Youd Eah Bah Eah. I reflected that it was probably the language that Jesus spoke in his lifetime.

Before leaving the exhibit, I thanked Gallegos for all he had taught me. “And thank you for what you’ve taught me,” he smiled.

Read more by Judith Fein

Judith Fein and Paul Ross have contributed articles and photos to more than 130 international publications, and are author/photographer for the recently released, award-winning experiential travel book SLOW TRAVEL NEW MEXICO: Unforgettable Personal Experiences in the Land of Enchantment. Judith is a popular speaker, opera librettist, playwright, former Hollywood screenwriter, and author of the books LIFE IS A TRIP; THE SPOON FROM MINKOWITZ; and HOW TO COMMUNICATE WITH THE DEAD. Paul also performs as PJ, a highly entertaining cowboy poet who has recently added a kosher cowboy poem to his repertoire. For information about the duo’s upcoming talks and events: https://www.Globaladventure.us

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

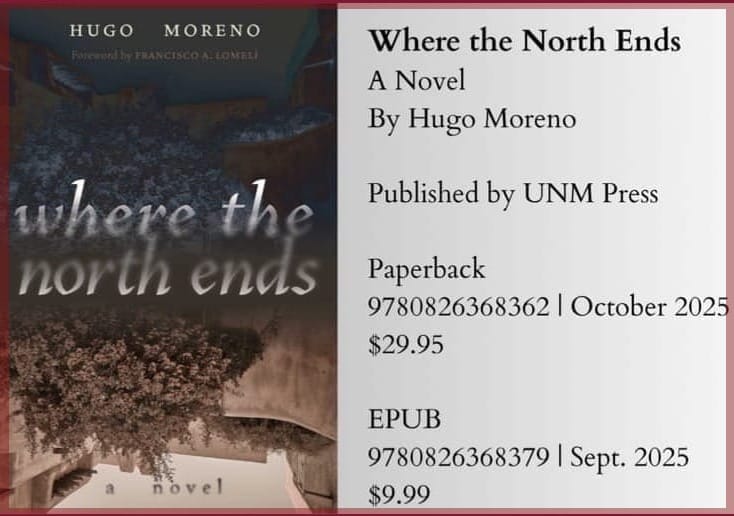

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.