Rabbi Dr. Jack Shlachter: Thirty Years as a Rabbi

Interview with Gloria Abella Ballen and Ron Duncan Hart

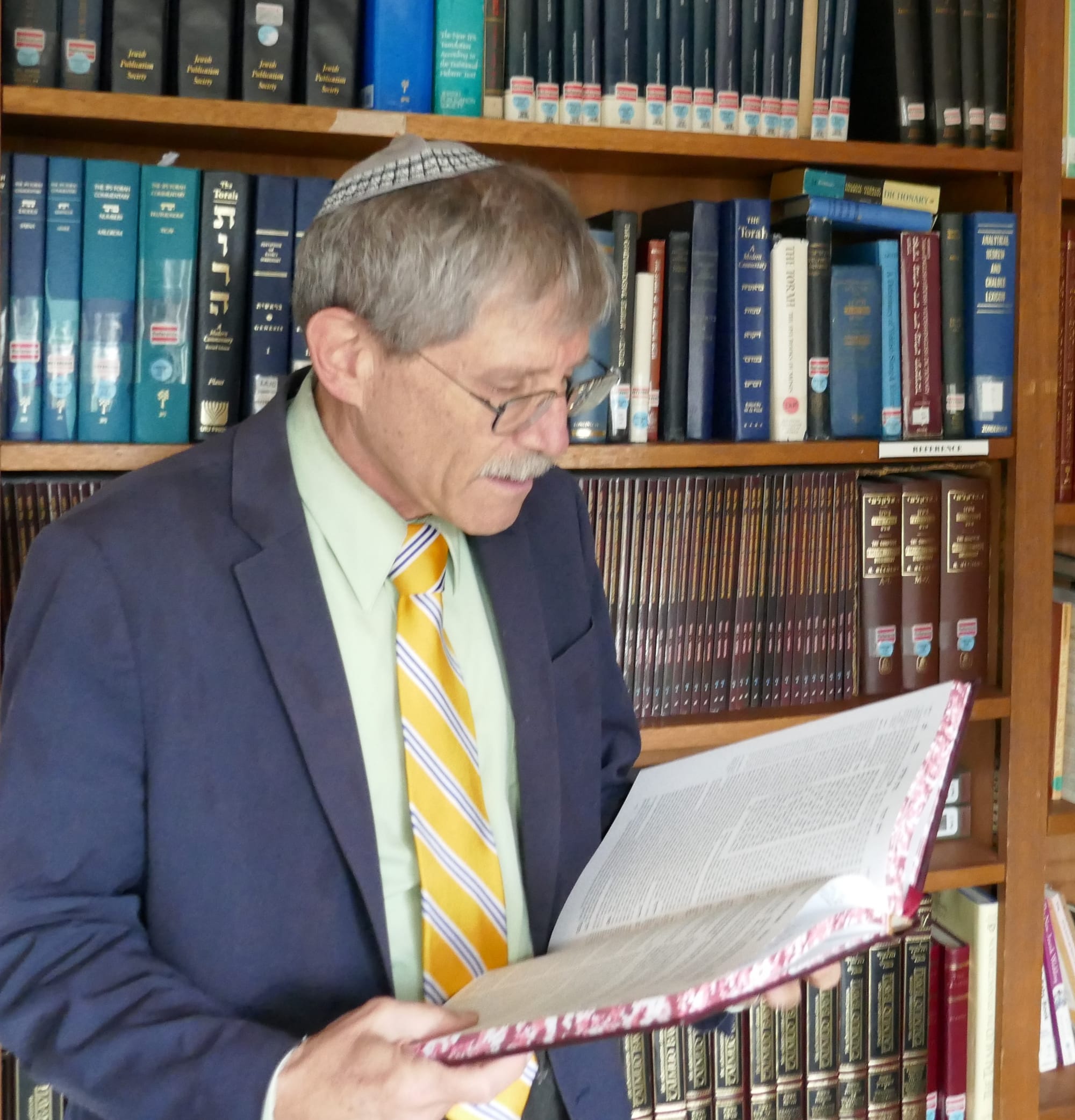

Rabbi Dr. Jack Shlachter is the rabbi of the Los Alamos Jewish Center and HaMakom in Santa Fe. He is a physicist and the past Head of the Theoretical Division of Los Alamos National Laboratory. This interview, edited for clarity, is on the occasion of his thirty years as a rabbi.

Gloria Abella Ballen. Thank you for talking with us as you complete this milestone of thirty years as a rabbi. Can we start by asking why you chose to become a rabbi?

Rabbi Jack Shlachter. I had gone to Sunday School as a child, but I had not really been involved in Jewish life in college or graduate school. While I was finishing my Ph.D. in physics, I was sent to the Los Alamos Lab. I arrived as a young student, not knowing anyone, and I began going to the synagogue as a connection with the community. I knew how to sing, and they encouraged me to keep coming. Rabbi Helman came up from Santa Fe on occasion to lead services, and I began to learn from him. Until then, I had thought Judaism was rather simple, but what I began to realize was that I had only known childhood Judaism. I had not known the full depth of thought in Jewish life. I began to buy books and educate myself on the richness of our tradition. Since I came to Judaism as an adult, I understand those people who have not discovered the beauty of our traditions and thought.

After five or six years of in-depth study, I was intrigued and wanted to learn more, and I became interested in the possibility of becoming a rabbi. Rabbi Helman sponsored me to go to a two-week intensive conference that the Reform movement had for fifteen lay leaders. The rabbis who were conducting the conference expressed a tension with the Orthodox movement because they felt they were not respected. I came away from that feeling that it was not helpful to define yourself as a reform Jew or a conservative Jew. I like to say that I am just Jewish, and I can draw from the wisdom of anyone who is Jewish.

We live in a Christian world, and I don’t think that Christianity encourages questioning or vigorous dispute the way Judaism does. The Talmud would be a lot shorter if the rabbis would simply tell you the answer whether you can eat the egg that was laid on the holiday, rather than having debated the subject. The Talmud preserves this challenge and question approach to issues of importance. To me, that is adult Judaism. We are given the gift of a brain, and we are supposed to use it to question and question, not simply to memorize things. We are not to only follow rules, but to question them, and ask what meaning do the rules have in our lives today.

For example, putting on tefflin. When the practice was developed, maybe it was as an amulet for protection, and today people might say I don’t believe in those things anymore, so let’s not do that. Other people say that we are told to put on tefflin in the book of Numbers, and so we do because we are told to do it. For me finding meaning, in the ritual of putting on tefflin is important. Tefflin involves the hand and arm and the head, and we only do it on workdays, not Shabbat. To me putting tefflin in the morning before starting work, means I need to approach my work with my head, thinking and understanding, as well as my hand and arm, the physical, more mechanical, exercise of my work. Putting tefflin means making my work more intelligible.

Ron Duncan Hart. Can you comment on the linkage between the abstraction of Jewish thought and that of physics?

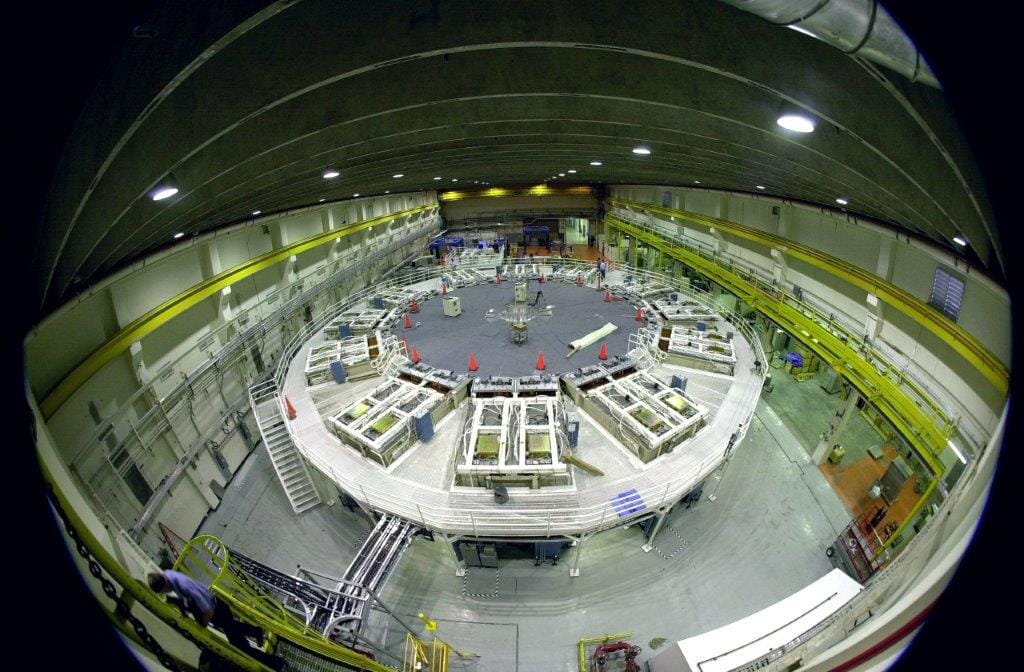

Rabbi Shlachter. The linkage between the abstraction in physics and Judaism is profound. Most physics is done with things that you cannot see, and yet we come up with ways to detect it and understand it. That is true with concepts in the spiritual world as well, God being a perfect example. We cannot see God. Chesed, kindness, generosity are intangible. Physicists are comfortable working with intangible concepts and challenging them. That is very much in the nature of Judaism and physics.

Another linkage between Judaism and physics can be seen in the debate over free will. I looked at ten medieval Jewish philosophers, and I found that they were all over the map. Some were very deterministic that everything was ordained, but there were others who were passionate about how important it is that we know that we have free will and make our own choices. It is exactly the same with modern neuroscience, the study of the brain and nervous system. One study shows the brain registering a decision shortly before we consciously make the decision. What does that say about free will? Both Jewish neuroscientists and physicists think in abstractions, and both have disagreements about whether we exercise free will. Ninety percent of the modern neuroscientists that I explored were Jewish, which probably explains the close parallel between Jewish thought and neuroscientic theory.

Ron. What was your process of becoming a rabbi?

Rabbi Shlachter. My rabbinic mentor was Rabbi Gershon Winkler, and my first contact with him was when he came to the Los Alamos Jewish Center to do a Shabbaton with teachings on Friday night and Saturday. He was considering moving to the region because his income was primarily from his writing, and he wanted a quiet place to write. Within a year he had moved to La Jara, New Mexico, which is near Cuba. I asked him if he would take me as a student, and he said that he would. I would drive to La Jara for sessions with him, and he would give me assignments. His training was very traditional, but he had taken his own path to understanding Judaism. He coined the term “flexodoxy”, which felt right to me, traditional but flexible. For example, one assignment was about the lulav and etrog at Sukkot. Since we do the ritual of shaking the lulav on every day, except Shabbat, he formulated a hypothetical situation of a small community in which people did not have a lulav or etrog at their home, but the synagogue did. How would you address the situation if the people came to the synagogue for Shabbat and ask the rabbi to teach them how to shake the lulav?

The way he taught was to go back to the earliest Jewish sources, which tend to be more flexible, and contrast them with later sources, which tend to become more rigid. He argued that if you could come up with a way that would be good for the Jewish people as a whole, that is what you should do as your rabbinic responsibility.

We have enough problems already. Subdividing the Jewish people into camps which have barriers is absolutely not helpful. We should be working together. We have plenty of people on the outside who are happy for us to be fighting each other.

Gloria. How do you understand the Torah?

Rabbi Shlachter. On the Torah, I believe that the issue of whether it is multiple documents put together is not so interesting to me. Historically, it has been treated as a very special document whoever wrote it. For more than 2,000 years brilliant Jews have grappled with the text to understand it in their environment. A thousand years ago Rashi had to understand the Torah influenced by the world that he lived in. With his writings he stays alive. Rabbis are able to argue with each other across the centuries through their writings even though they might be dead.

When I am studying Torah, I want to know what the various Jewish leaders across time have had to say about this text. That is the Torah that we have. The words themselves are available to anyone. After I have looked at what Rashi has to say, and the Rambam and Ibn Ezra, and Sforno, all the commentators are trying to tell me, what resonates with me today and is there something in our society that this can inform? There are wonderful commentators today; Shai Held has a wonderful two-volume set of commentaries on every Torah portion. It goes back to earlier sources, and I think that is important.

When I am studying Torah, I like to do it in a conversational setting with other people, always asking what is the relevance for us today. The passage might talk about going in to conquer the people living in the land that you are supposed to inherit. Does that not have something to tell us about today? Can we build on that to inform our views on the situation in Israel? We might disagree with what the Torah has to say, but we should know what has been thought of over the millennia.

In the Torah portion last week, we had the deaths of Aaron and Miriam. Moses is very careful to insure the continuity of Aaron and his function after he dies. The vestments are transferred to Aaron’s son, who becomes the new High Priest. At the end of his life, Moses transfers his authority to Joshua. So, you can consider that was the transfer of political/military leadership and Aaron was the religious/ritual leadership, and both have successors who carry on the tradition. Miriam also dies, and what has been done to insure the continuity of Miriam’s contributions? There is nothing in the text. The men have generally been ignorant or have ignored the role of Miriam, and what she did.

I read a feminist scholar recently who mentioned that immediately after the mention of Miriam’s death is the section where the people are complaining about not having water, hence the tradition of Miriam’s well. So, was she guaranteeing water for the people? We can go deeper than that. Water is a metaphor. It is something that gives us life. It is something that we have to have. Moses did not do much to guarantee that her teachings were transmitted. Miriam had the wisdom to teach the women, so that they would continue her teachings in the households. I thought that interpretation was brilliant. Although we are years beyond the feminist movement, women still do not have the authority and respect that they should have.

Ron. What about oral tradition and the Torah?

Rabbi Shlachter. At one point, I was in the study of a traditional rabbi, and I came across the Soncino Midrash Rabbah translated into English. I remembered being taught in Sunday School about Abraham destroying his father’s idols, but that story is not in the Torah. I found it in the Midrash, also the story of Moses touching a live coal to his lips, producing his speech impediment. This is part of oral tradition, and it was felt to be important enough to write down. It gives us insight into early generations, and it is very creative. I like to tell people that Midrash is the back story. With oral tradition, you can fill in the details of the original story, as long as it does not do harm to the original text. The back story can give you another perspective to understand the original story in your terms.

The Torah has shaped the Jewish people over millennia. Whether we think it was written by people or Divinely inspired, its influence has shaped the Jewish people over the centuries. The Torah is our book. This is who we are as a Jewish people.

Beverly & Rabbi Jack Shlachter in Los Alamos photo © by Ashley Pond, and At Purim in Santa Fe © / nmjewishjournal.com

Rabbi Dr. Jack Shlachter is the rabbi of the Los Alamos Jewish Center and HaMakom in Santa Fe. He is a physicist and the past Head of the Theoretical Division of Los Alamos Labs. In addition to serving in Los Alamos, he has also worked as a physicist at the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization. As a rabbi, he has led high holiday services around the world from Vienna and Warsaw to Long Island and from Beijing to Thailand. He is a cornerstone of Jewish life in Los Alamos and Santa Fe. He has the largest library of Jewish books in northern New Mexico and most likely in the entire state.

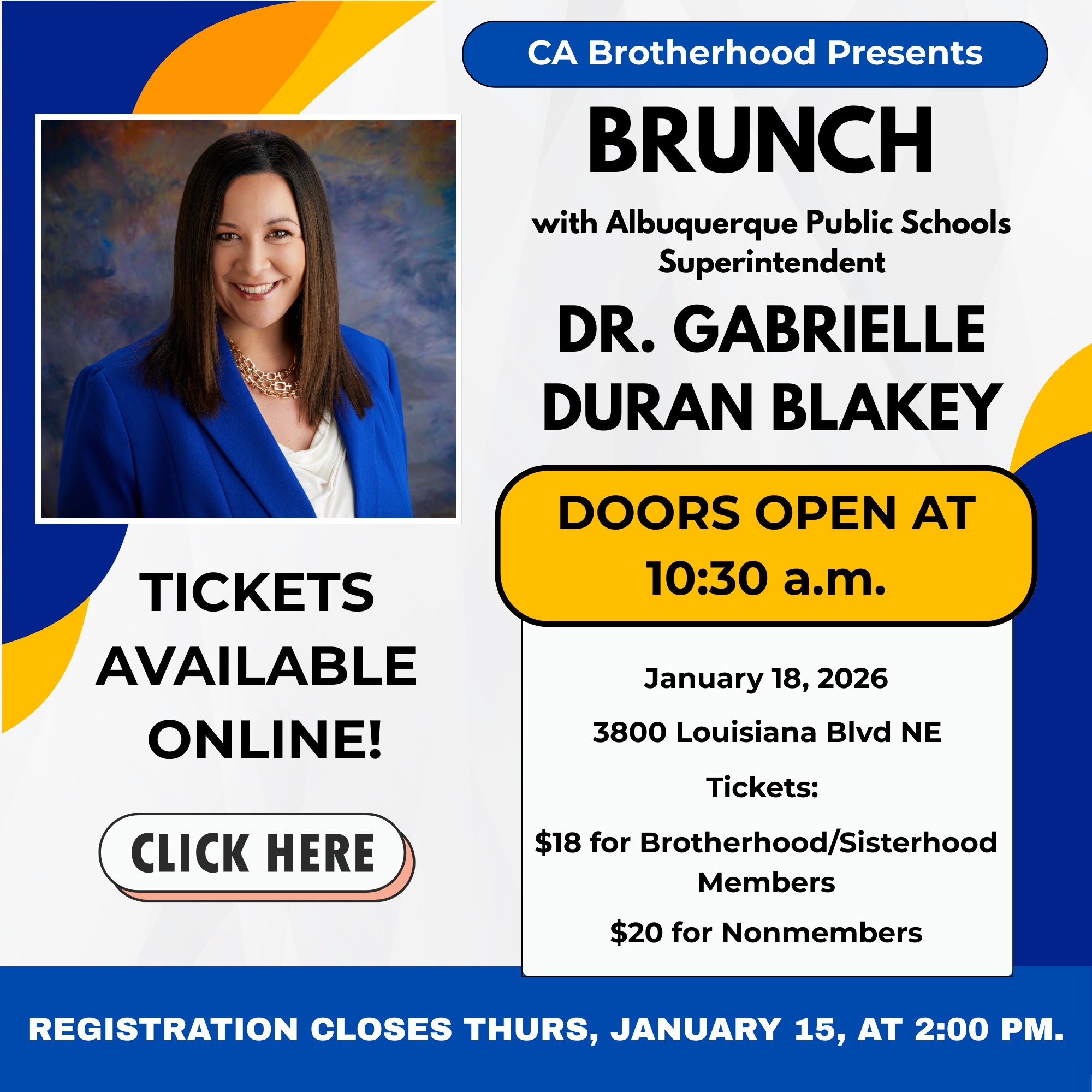

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

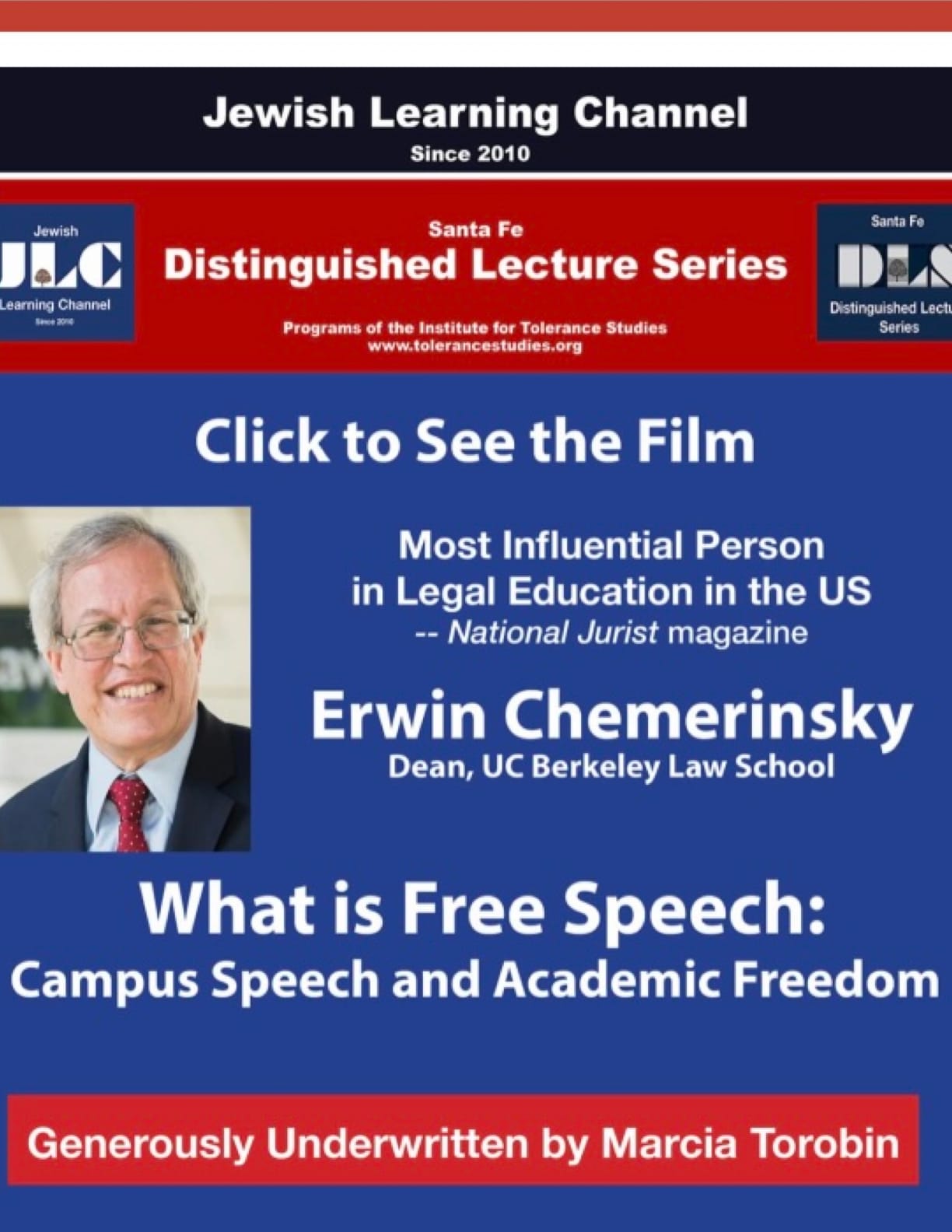

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

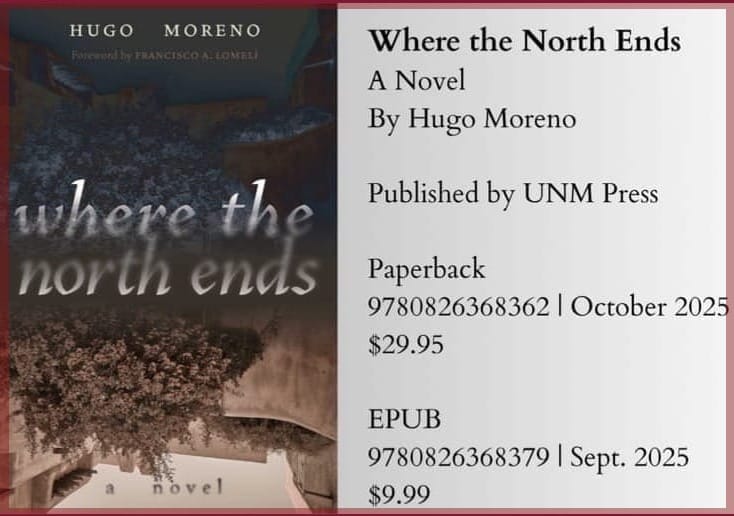

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.