The Inside Story of the Return of Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo

By Bobbie Greene Kilberg

Blue Lake is a sacred site for the Taos Pueblo, central to their religion, and in 1906 Blue Lake and its surrounding 48,000 acres of watershed land were taken away from the Pueblo by the Federal Government and incorporated into the neighboring national forest. The Taos people fought for 64 years to have it returned. As part of the White House team that drafted the legislation for the return of Blue Lake, I was in the right place at the right time to help make it happen.

I had graduated from Yale Law School in the spring of 1969 and was selected as a White House Fellow, working for John Ehrlichman, the head of the domestic policy council. I had been interested in Native American rights, and I did my thesis at Yale Law school on Indian education. I had also spent several weeks on the Navajo reservation working on an education lawsuit against the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

As you know, President Nixon was a complicated person. He did have a strong sense of a moral belief in equal opportunity, and he wanted to remedy the history of termination and assimilation that had long dominated the Federal Government’s Indian policy. Nixon’s parents were Quakers, and they re-enforced his sense of the importance of non-discrimination and equal opportunity. Another factor was his college football coach. Nixon was on the football team at Whittier College, and he was very close to his coach, Wallace “Chief” Newman, who was of the Luiseño tribe in California. He viewed Newman as a second father and was upset that Newman was discriminated against because of his race. He believed that Newman was a superior coach and if he had not been Native American, he could have been a coach in the Big 10. Nixon carried that sense of injustice toward Native Americans with him to the White House.

As President, Nixon was an activist domestic policy proponent. With John Ehrlichman directing the domestic policy council, Nixon crafted domestic initiatives that changed the future for Native Americans. The Indian Self-Determination Act and the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act were formulated at his direction. They redefined Indian relations, recognizing tribal sovereignty and self-determination, giving rights to Native Americans, and reversing the termination and assimilation policy.

I was fortunate to attend the White House senior staff meeting in October 1969 that started this process. As a White House Fellow, I sat at the side of the room and not at the table. John Ehrlichman chaired the meeting and Len Garment, counsel to the president, who would play a major part in formulating the new Indian policy, was also at the table. John said that the President wanted to review federal Native American policy because he was not satisfied with the state of Indian opportunity in the country.

John then asked whether anyone in the room had expertise in Native American affairs. There was total silence. I hesitated for a while because I was supposed to be a silent backbencher but, when no one else spoke up, I raised my hand and explained my background on Native American issues. Ehrlichman assigned me to manage the project with Len Garment as a senior advisor and his assistant, Brad Patterson, as part of the team.

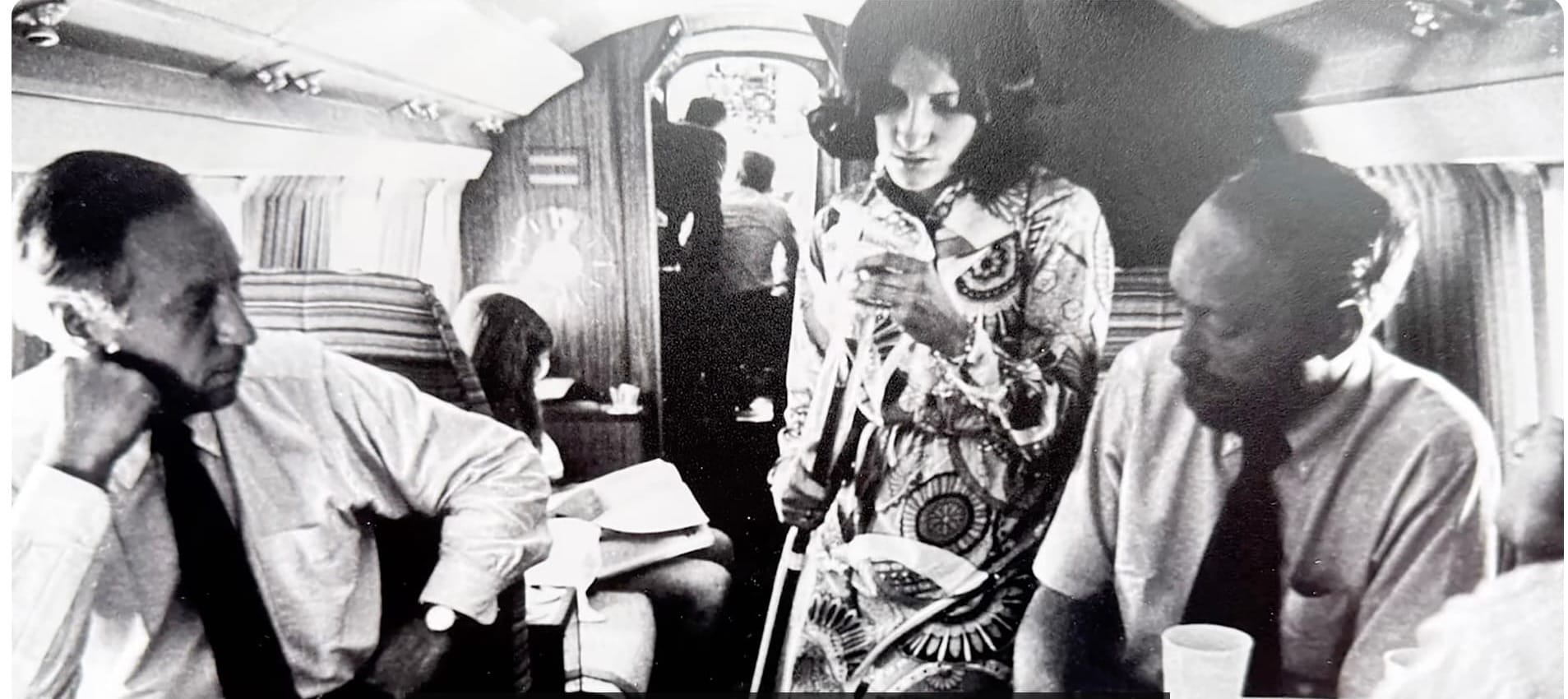

We started by consulting with Bob Robertson, Director of the National Council on Indian Opportunity (NCIO), which consisted of eight cabinet and eight Indian members. In January 1970, Vice President Agnew held a meeting of NCIO with us in the West Wing Roosevelt room to discuss their general recommendations. Ladonna Harris, founder of Americans for Indian Opportunity and a member of the Comanche tribe from Oklahoma, rose to speak on behalf of the Indian members. She was so moving, powerful, and charismatic that the room was literally spellbound. She was also the wife of Oklahoma Democratic Senator Fred Harris. In later years, they lived in New Mexico.

We spent the next few months synthesizing the NCIO recommendations and added important specifics and included other initiatives, representing the perspectives of all participants. Ehrlichman presented the memorandum on Indian policy to the President in late April 1970. The recommendations were:

- Self-determination with rejection of termination

- The right for Indian tribes to control and operate federal programs through contracts

- Education reform, including the right of Indian communities to control their own schools

- Economic development legislation

- Major additional resources for Indian health and urban Indian programs

- Establishment of an Indian trust counsel authority

- Creation of an Interior Department assistant secretary for Indian and Territorial affairs

- And the return of Blue Lake and its surrounding lands to the Taos Pueblo.

When the new Indian policy had been formulated and was to be announced, I was carrying 200 copies of the press release to the White House press briefing room to give to reporters. I saw Ken BeLieu, the White House Director of Senate Relations, racing towards me from the Rose Garden. He literally ran into me knocking me down, and the 200 copies of the press releases flew into the air. As Ken apologized and helped me up, I asked him what the heck he was doing, and he said that the Indian message could not be released. New Mexico’s senior Senator Clinton Anderson, a Democrat, opposed the return of Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo because of the opposition of ranchers, and he was threatening to vote against the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty – the ABM – if the president continued with the recommendation to return Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo.

I took Ken upstairs to explain that to Ehrlichman, who listened to him and immediately called the President’s secretary, Rose Woods, saying he needed to talk with the President about an important matter. I walked with John and Ken to the Oval Office but, since I was a junior staffer, I waited in the anteroom. After what seemed like a long time, the Oval Office door opened, and I saw the President wink toward me. Now the President was not known to wink at anyone, but I swore he winked at me. I looked at Ehrlichman and BeLieu and asked what happened. John was smiling broadly, and Ken looked like a Mac truck had run over him. The President had instructed Ken to tell Senator Anderson, and I quote, “That his decision stands in support of Blue Lake and that, if Anderson did not like it, he could vote against the ABM, and he could go [4 letter word] himself.”

And what is more, Ehrlichman said, instead of a press release, we are going to invite the Taos Pueblo leadership to the White House to release the Indian message in a formal ceremony, declaring the President’s strong support for the return of Blue Lake along with the entire Indian policy message.

On July 8, 1970 Taos Pueblo tribal and religious leaders met in the White House with President Nixon, Vice President Agnew, Secretary of the Interior Wally Hickel, other cabinet members, John Ehrlichman, Len Garment, and me. The meeting was held in the Cabinet Room, which was always reserved for meetings with Heads of State and their delegations, Senate and House leadership and Governors.

The President was making the point that Taos Pueblo and the other Indian tribes in the country were sovereign nations and were due that respect. It is of personal importance to me to note that Gil Suazo, the Pueblo youth representative, and I were the two youngest people in the room. Gil went on to become the pueblo governor in later years and has kept the history of the return of Blue Lake alive. We continue to be close friends. The next day the New York Times reported the new Indian policy statement as a prominent front-page story above the fold.

Then, a huge problem surfaced when the Senate Interior and Insular Affairs Committee voted to reject the Blue Lake legislation, which would have killed the bill because a Senate Interior Committee’s vote had never been overturned before by the full Senate. In a bipartisan effort by Democratic Senator Fred Harris of Oklahoma, Ladonna Harris, and President Nixon, we forced a vote in the full Senate on the legislation. What a strange but effective bipartisan trio were the President, Fred, and LaDonna Harris. Between John Ehrlichman, Len Garment, the President, Ladonna and Fred Harris, and me, we spoke directly with almost every U.S. Senator. We were assisted in that lobbying effort by Democrats McGovern and Kennedy and Republicans Griffen and Mathias. President Nixon called Senator Barry Goldwater, who would not say how he was going to vote. “You will just have to wait and see,” he said.

Then, for the Senate vote on the bill on December 2nd, I sat in the gallery with the Taos delegation, Ladonna Harris, lawyers representing the Pueblo and a few others. To our utter amazement, the vote was 70 – 12 in favor of passage. There was a clear gasp from the gallery when it passed because we had expected a much closer vote. The key had been Senator Barry Goldwater, the dean of the Senate. After Senator Harris had given an eloquent speech, Senator Goldwater unexpectedly stood up, and all the senators on the senate floor turned to listen. Goldwater forcefully declared that, after thinking about it long and hard, he was supporting the return of Blue Lake to the Taos Pueblo because it was the right thing to do.

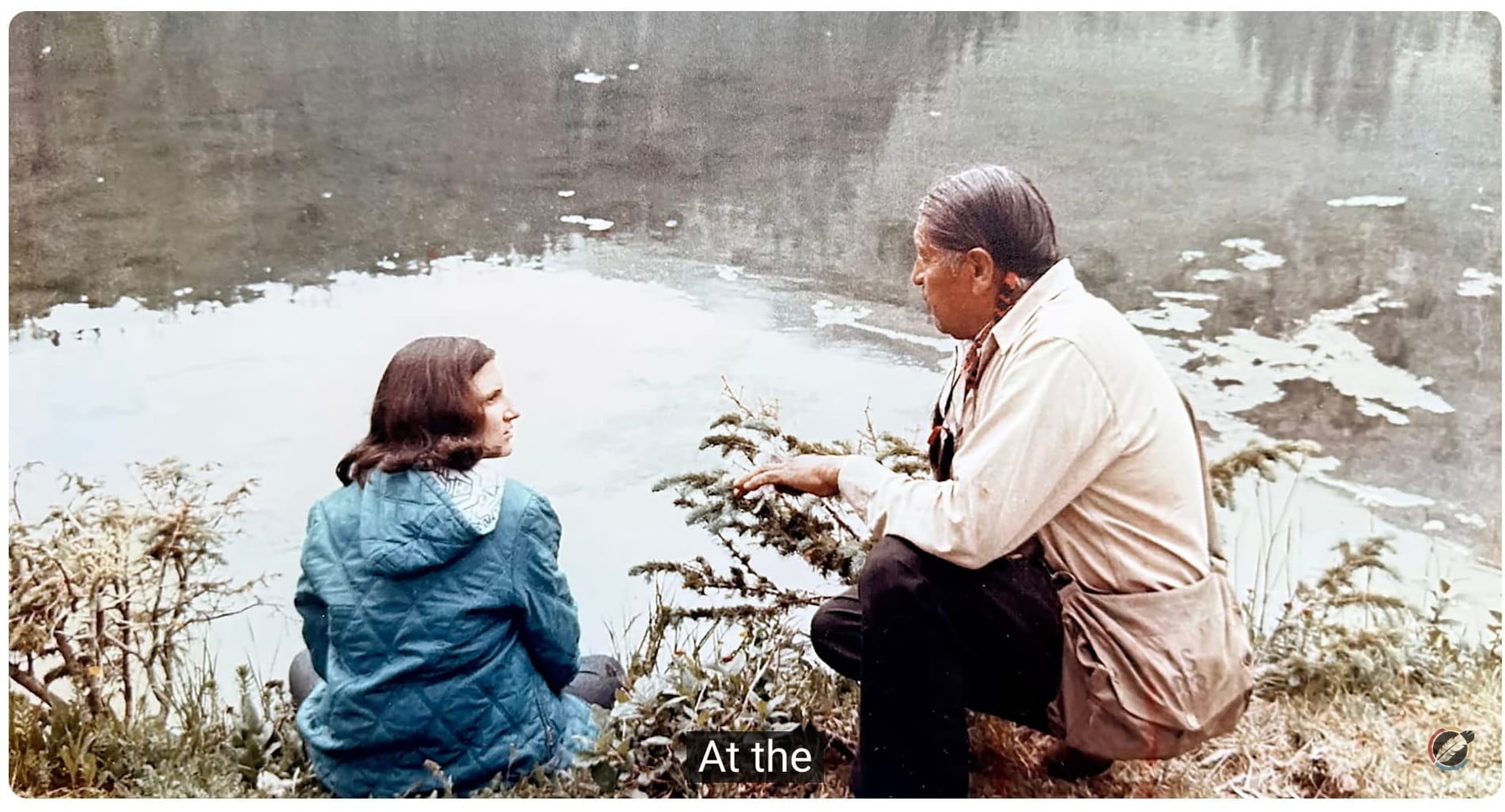

In the Senate gallery, visitors were never supposed to talk, applaud, or stand. Even chewing gum was prohibited. But Cacique Juan de Jesus Romero stood up and hoisted two canes high above his head, one that President Abraham Lincoln had given to the Pueblo and one that President Nixon had given to the Pueblo in July 1970 – both to honor the Taos people. The entire gallery stood with him, and then all the Senators on the floor stood, and the place erupted in sustained applause.

Finally, on December 15, 1970, as a twenty-five-year-old White House Fellow, I was in charge of the logistics for the Blue Lake signing ceremony in the East Room of the White House. The East Room was fully decorated for Christmas, and the setting was magical. President Nixon sat at the signing table with Cacique Romero and Paul Bernal, the translator, standing next to him. In the audience were the Taos Pueblo delegation, cabinet members, members of Congress, and senior White House staff. The President asked the Cacique to start with a prayer, and the room became completely silent. Afterwards the President stood and said this was the start of “a new road which leads us to justice in the treatment of those who were the first Americans.” He sat down, took his pen, and signed the “Return of the Blue Lake Act”. It moved me to tears.

As a young staffer, I had never spent personal time with the President but, after the event, he invited me to walk with him to his motorcade. The ceremony had gone over the scheduled time limit, and he was late for a speech. I apologized for the ceremony having taken so long. President Nixon turned and stared directly at me, put his hand on my shoulder and said: “Young lady, that ceremony was one of the highlights of my presidency. It was exceptionally meaningful, and I only wish it could have continued even longer. I am very proud of what we did today.”

Bobbie Kilberg was a White House Fellow to John Ehrlichman in the Nixon White House and then served three additional presidents, including President George H.W. Bush as Deputy Assistant to the President for Public Liaison and later for Intergovernmental Affairs. She retired as CEO of the Northern Virginia Technology Council in September 2020 after serving in that position for 22 years. Her husband William Kilberg has also retired as a senior partner of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, a leading global law firm. Bobbie and her husband have been part-time residents of Santa Fe for decades. John Ehrlichman was also a resident of Santa Fe for many years after leaving government.

Watch the video The Return of Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo by For Our People: Stories of Tribal Self-Governance.

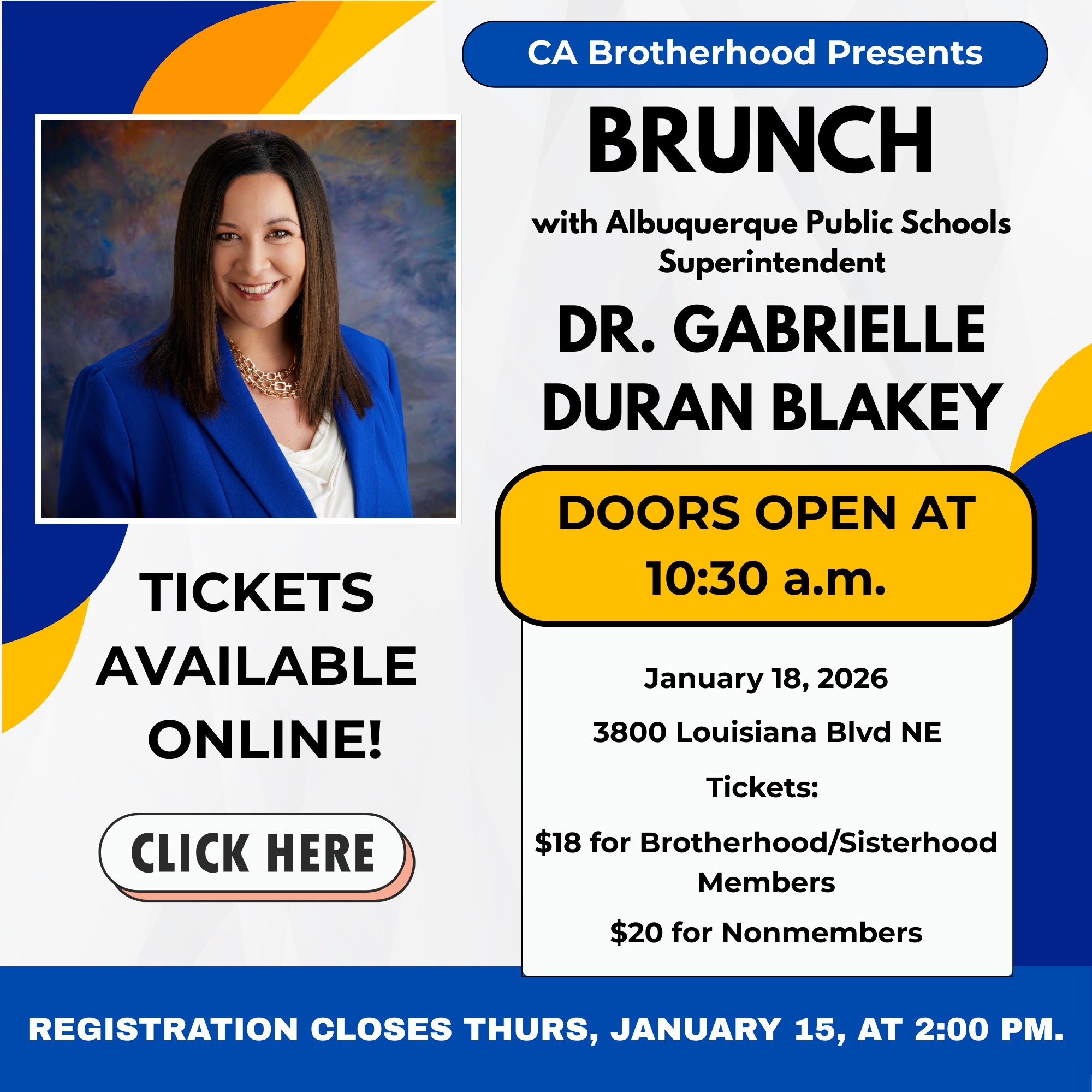

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

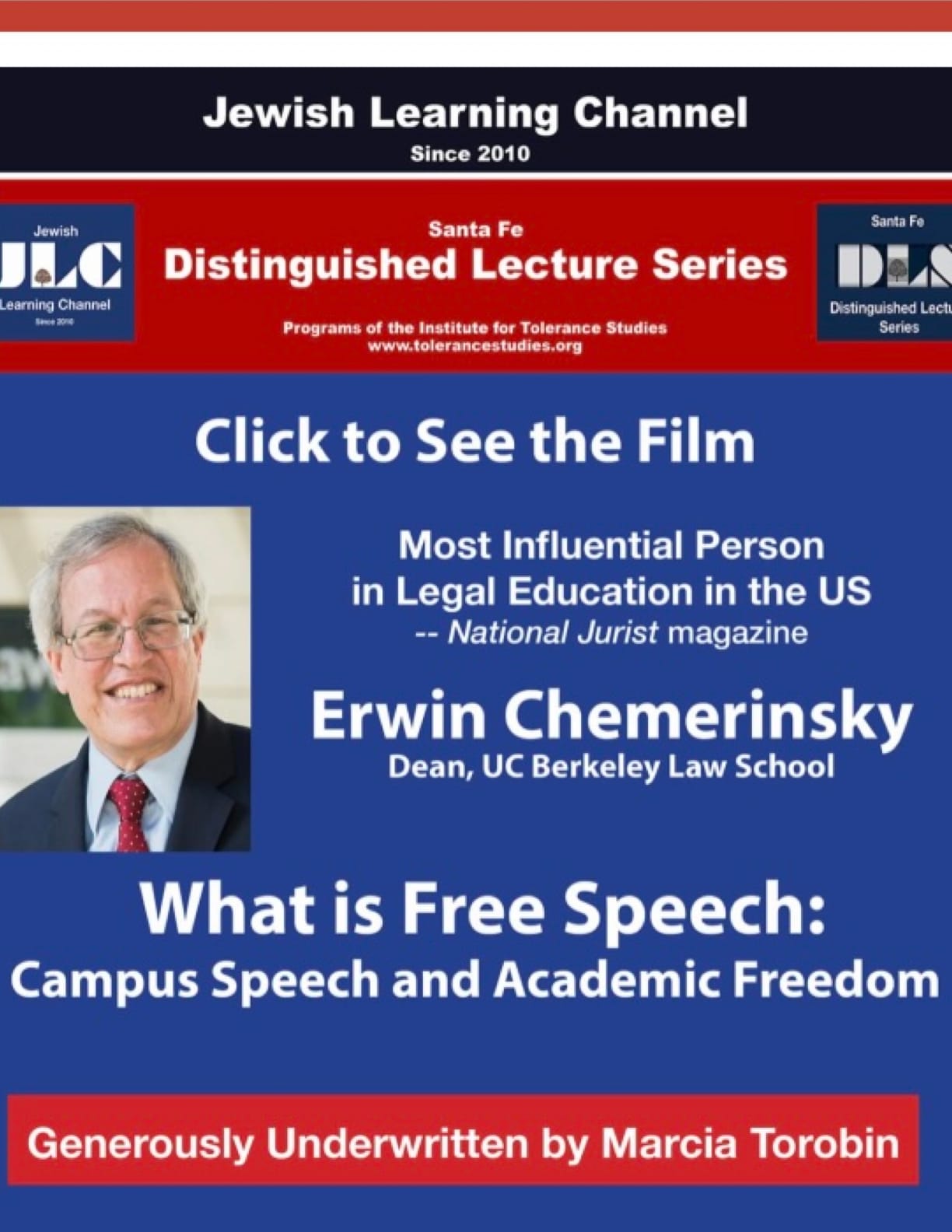

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

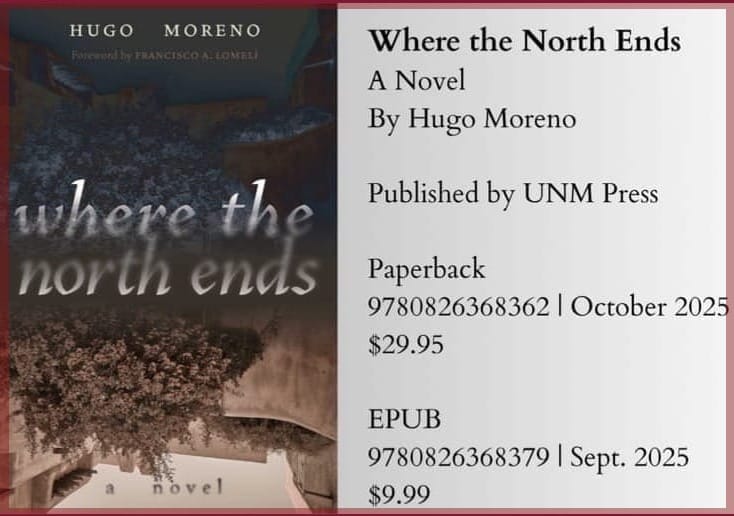

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.