Etty and the Etty Project: Susan Stein in New Mexico

by Dianne R. Layden, Ph.D.

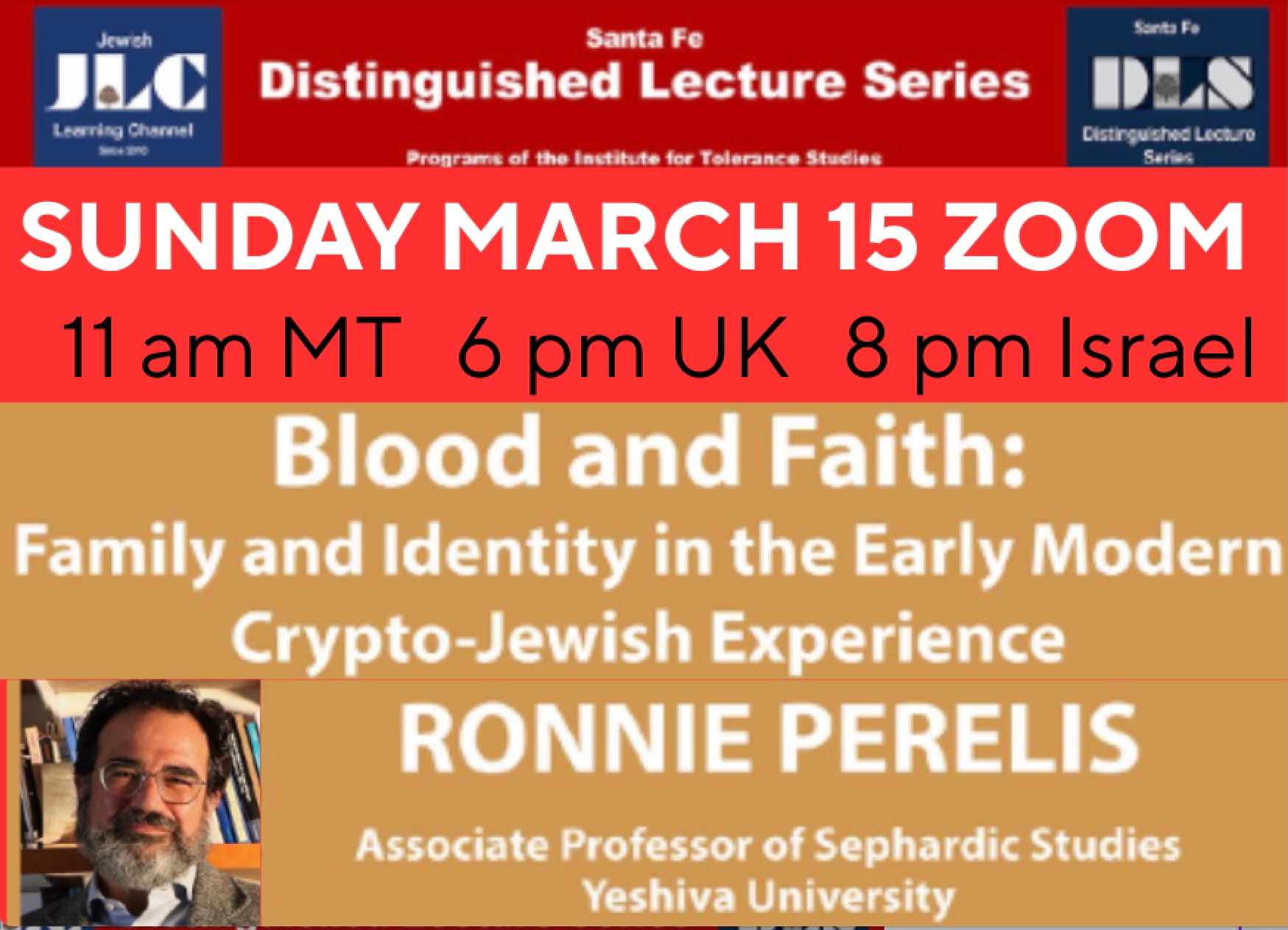

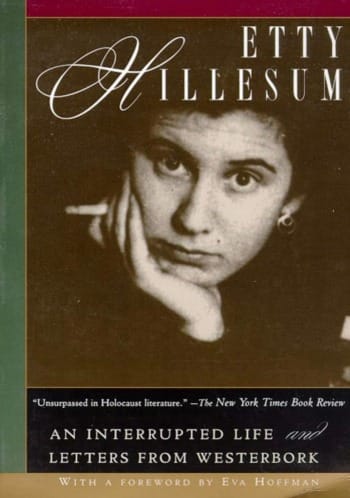

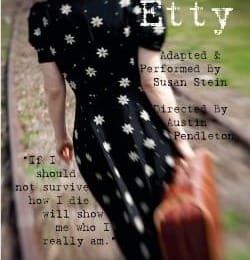

The short play Etty about the life of Dutch woman Esther “Etty” Hillesum (1914-1943) during the German occupation was performed by Susan Stein in schools and houses of worship in New Mexico in October 2025.* I saw the performance in Albuquerque at Congregation Albert on October 19th and was moved and inspired. Stein is an actor, playwright, and teaching artist who adapted the play as a one-woman show in Etty’s words from her diaries and letters, An Interrupted Life: The Diaries, 1941-1943, and Letters from Westerbork. The book was first published in the Netherlands in 1981 and then in an English translation by Pantheon Books in 1983.

In the second act, the audience is asked to join the conversation in a dialogue about human rights, resistance, and personal responsibility. The conversations began years ago when people wouldn’t leave after the play was over. In an interview with me, Stein said, “They started emailing me or staying in their seats or waiting until the lights came up to talk. People have not seen a play like this . . . [and] want to talk back.” Stein has portrayed Etty in the United States, Europe, and Israel. Director Austin Pendleton is a well-known stage, film, and television actor, playwright, theater director, and teaching artist.

In 1994, Stein bought Etty’s diaries at a yard sale and decided to write a play in Etty’s ardent words to share her story with a large audience. She spent two years working with the diaries, conducted research, sought scholarly guidance, and began working with Pendleton, who would direct the play. Stein began reading a bit of script to friends who provided feedback. In our interview she stated, “I started getting invited more and more places, and then I had a full draft of a script and the venues turned from living rooms to houses of worship to theaters.” The first actual performance was in 2009 in Ghent, Belgium. In that year, Amnesty International nominated Etty for its Freedom of Expression Award.

In eloquent language, this engrossing play tells of Etty’s search for truth in life, in love, in God, and within herself amidst the arrival of the Holocaust in Holland.1 Stein’s quiet portrayal of this complex woman is nuanced and compelling.

Stein averred her play is not about Etty’s story, but her sensibility, “her struggle against despair and her commitment to sustain humanity in the face of Nazi brutality.”

The Etty Project (www.ettyproject.org) provides educational workshops in schools, universities, houses of worship, prisons, and other venues that consider the dangers and consequences of racism, anti-Semitism, and discrimination, foster empathy, and promote social justice. Workshops were held at a Santa Fe high school in October 2025. In prisons, teaching artists help inmates find their voices and share their stories aloud. Over 70,000 people have attended an Etty performance; thousands of students have participated in Etty Project classes; and the Etty Project has visited prisons throughout the U.S., Scotland, and England.

Stein called Etty a prison story: “The prison performances are the most powerful. Incarcerated people respond strongly to the play, and although they do not compare their imprisonment with Etty’s, they are inspired by how she lives with her imprisonment.” Performances in prisons led Stein to begin to teach workshops in prisons, particularly writing workshops.

Etty was born on January 15, 1914 in Middelburg, Netherlands. She was an avid reader and an intellectual. In Amsterdam in 1941, she had earned a law degree and was studying Russian at a university. Suffering from depression, Etty became a patient of Julius Spier, a Jungian psychologist “cum palm reader and general guru” (Hillesum ix), who encouraged her to keep a diary of her innermost thoughts that she began at age 27. She also became Spier’s lover. Spier’s treatment methods have been described as “odd”: “He insisted that ‘body and soul are one' and that sessions between analyst and patient must therefore begin with a wrestling match. Etty's pride is that her first time with Spier she floored him,” wrote Terrence Des Pres in "Eros, God and Auschwitz," New York Times, 1984. Spier died in September 1942.

In the foreword to the 1996 edition of Hillesum’s book, author Eva Hoffman wrote, “Through her real and metaphorical wrestlings with Spier, she trained herself to check her impulses and restrain the impetuousness of her needs. . . . [S]he learned the kind of love that is closer to selfless agape than to urgent eros and that combines deep sympathy with calm detachment.”

After Holland capitulated to Germany in May 1940, the Nazis fired Jews from jobs, barred them from stores frequented by non-Jews, and created ghettoes and work camps. J. G. Gaarlandt, who wrote the introduction to Hillesum’s book, is the Dutch writer who discovered Etty’s war diaries and edited them for publication. He wrote, “In April 1942, the Germans launched their first major roundups of the Jews, required them to wear the yellow star, and, after moving all the Jews they could find to Amsterdam, declared the provinces ‘judenrein.’” Etty comes to see her writings “as an act of bearing witness to her time and her people. But at first she is absorbed in herself and for many pages the catastrophe in progress is mentioned only in passing. . . . Only after Amsterdam’s Jews are forced to wear the yellow star . . . does the horror begin to close in. Then she writes: ‘Only a few months ago I still believed that politics did not touch me and wondered if that was “unworldliness,” a lack of real understanding. Now I don’t ask such questions anymore’” (Des Pres).

Nazis wanted to concentrate all Jews in Westerbork, a transit camp built for 1,500 German Jews who fled to the Netherlands before the war that would house 30,000-40,000 people. Etty left for Westerbork in June 1943. She wrote in a letter that “mud and misery were the essence of Westerbork – as were sickness and overcrowding – a universe of noise and fear crammed into a patch of heath half a kilometer square.” And it was in this hell she wrote again and again, ‘Despite everything, life is full of beauty and meaning’” (Hillesum xx). Gaarlandt wrote, “She was determined to share the fate of her fellow Jews, without bravado, but also without despair.” Etty rejected all attempts by friends to save herself.

Westerbork was the last stop before Auschwitz for over 100,000 Dutch Jews.2 On September 7, 1943, Etty’s parents, Etty, and her brother Mischa were deported to Auschwitz – records state her parents died on September 10, 1943, Etty on November 30, 1943, at age 29, and Mischa on March 31, 1944.

In his review of Hillesum’s book, Terrence Des Pres notes that Anne Frank (1929-1945) “also comes to mind, not merely because she, too, kept diaries but because both Anne and Etty shared a faith in human decency that seems, in the light of history, more than their situation justified.” Etty called writing her greatest talent, gave her diaries to friends, and wanted them published.

Examples of Etty’s eloquence abound. In her first diary entry on March 9, 1941, she wrote, “I am blessed enough intellectually to be able to fathom most subjects, to express myself clearly on most things; I seem to be a match for most of life’s problems, and yet deep down something like a tightly wound ball of twine binds me relentlessly, and at times I am nothing more or less than a miserable, frightened creature, despite the clarity with which I can express myself.”

Etty addressed God frequently, not as a savior but as a power she must nurture within herself: On July 12, 1942, she wrote, “Alas, there doesn’t seem to be much You Yourself can do about our circumstances, about our lives. Neither do I hold You responsible. You can help us, but we must help You and defend Your dwelling place inside us to the last.”

The last line of Etty’s diary, written on December 11, 1942, is, “We should be willing to act as a balm for all wounds.”

- Editor's Note: Susan Stein and the Etty Project came to New Mexico through the generosity of Kristina Flanagan, who sponsored a full-week residency for Susan at the New Mexico School for the Arts. Kristina had read Etty’s journals, which she found "life-changing," and wanted to bring Susan to teach at the school in an innovative program facilitated by instructor Alex Martinez and coordinated by the NMSA-Art Institute's president Cindy Montoya. While at the School, Susan taught the diaries of Etty and of other young people who also wrote journals during the Holocaust, led a writing workshop, taught the history of the Japanese internment camps in New Mexico, including the camp in Santa Fe, and performed Etty. In addition to the school residency, Doris Francis arranged for performances of Etty to an interfaith audience at HaMakom Santa Fe, followed by a deep-dive discussion of her diaries for the combined book groups of HaMakom and Temple Beth Shalom; to Congregation Albert in Albuquerque; and to El Castillo, a senior residence in Santa Fe. Audience response was strongly favorable.

Susan has been invited to return to New Mexico the week of February 9th for a residency at the Albuquerque High School to coordinate with their production of Anne Frank’s diary. She has also been asked back to the New Mexico School for the Arts. For more information on bringing Etty to New Mexico, please contact the Etty Project at http://www.ettyproject.org/ or write to Etty Project, 310 West 99th St.#808, New York, NY 10025.

Dianne Layden is a semi-retired professor and writer in Albuquerque. Her field is American Studies. She published a booklet in 2024 about historic Temple Montefiore in Las Vegas, NM, which is available on the New Mexico Jewish Historical website, NMJHS.org. Dr. Layden won a national award for her 2017 article in Legacy, the NMJHS newsletter, about New Mexico Holocaust survivors. In 2022-2025, she portrayed Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg for the New Mexico Humanities Council.

Also by Dianne Layden: Tribute to Frances Levine’s New Book, Crossings: Women on the Santa Fe Trail

Notes

1 In 2025, an estimated 220,800 Holocaust survivors lived in over 90 countries around the world, according to The Claims Conference (“2025”). Their median age is 87 years, 96% are child survivors born between 1928 and 1946, 50% live in Israel, and 61% are female. Seventy percent are expected to pass away in the next 10 years (“70”).

2 Of the approximately 160,000 Jews in the Netherlands at the time of World War II, “107,000 were deported and only 5,200 of them returned alive: about 73 percent of them did not survive the Holocaust. With this number, the Dutch Jews suffered the highest number of victims per capita in the Holocaust” (“The Difficult Position”).

References

Des Pres, Terrence. “Eros, God and Auschwitz.” The New York Times, January 29, 1984. Review of An Interrupted Life: The Diaries of Etty Hillesum, 1941-1943. Introduced by J. G. Gaarlandt. Translated by Arno Pomerans. 226 pp. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983.

“The Difficult Position of the Jewish Council (De Joodsche Raad).” HannahByron.com, June 30, 2023.

Hillesum, Etty. An Interrupted Life: The Diaries, 1941-1943, and Letters from Westerbork. A Holt Paperback, Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1996.

“70% of Holocaust survivors will pass away in next 10 years, report shows,” PBS.org, April 22, 2025.

“Susan Stein.” Teach the Holocaust. https://teachtheholocaust.weebly.com/

“2025 Demographic Report.” The Claims Conference

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

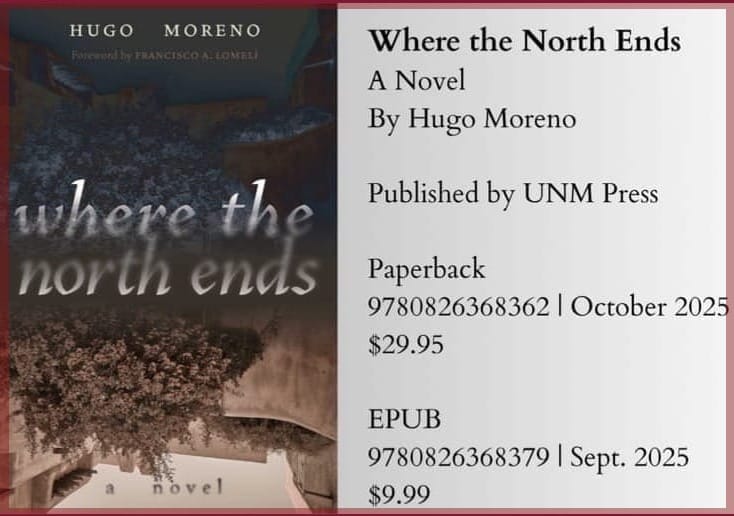

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.