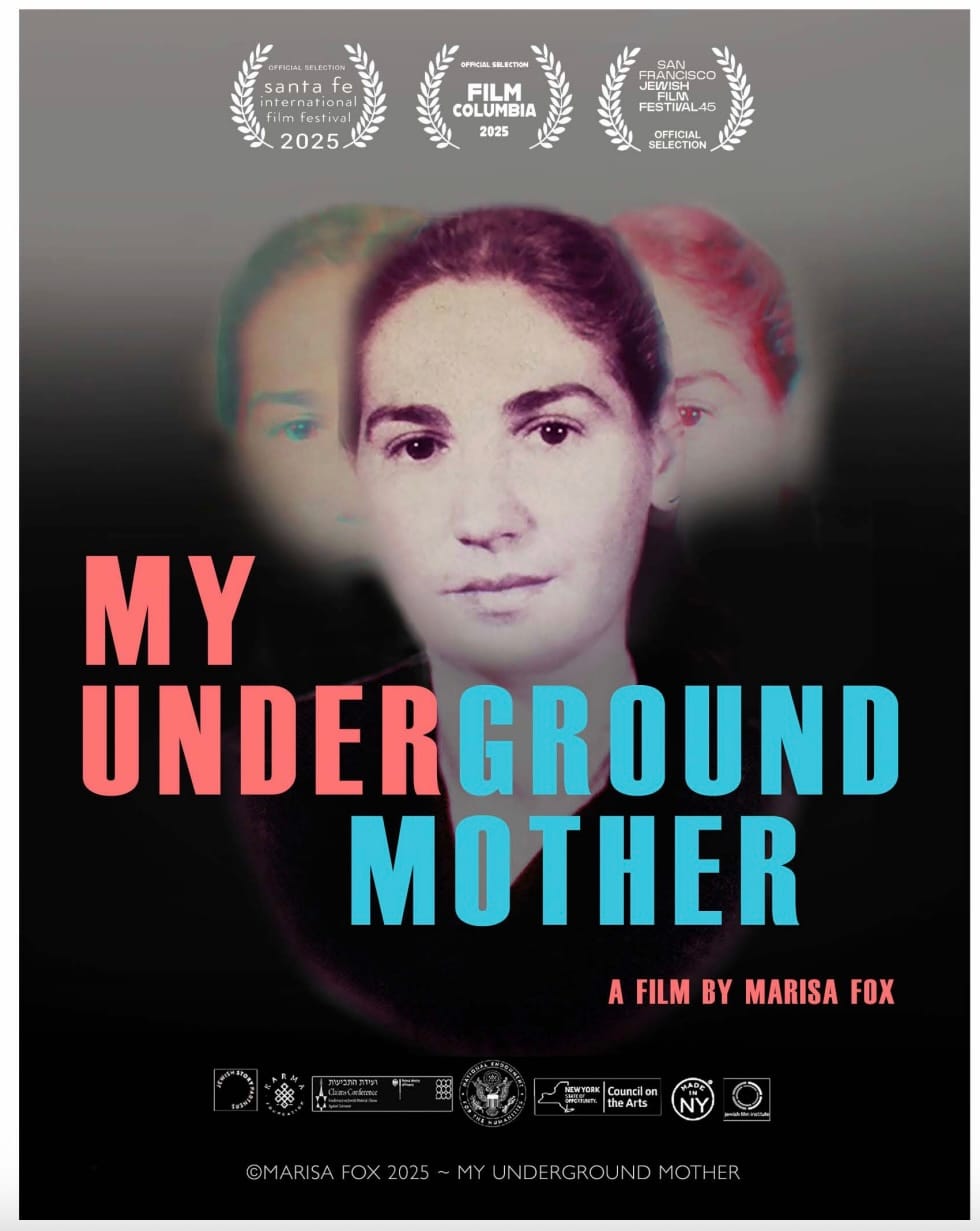

Personal essay written on Oct. 13th from Marisa Fox, the Filmmaker of "My Underground Mother" SFIFF Official Selection

"Freedom fighter, double agent, femme fatale — Tamar said she was all three. Decades after her death, a page she wrote in a diary from a Nazi-run women’s camp reveals a hidden identity, leading her journalist daughter on a global reckoning with the secrets she took to her grave."

I had the opportunity to preview the film and want to say this about it: I think a real work of art raises more questions than it answers. The film “My Underground Mother” wrestles with impossible questions, and we are left seeking answers and the realization that any resolution will always be imperfect. One issue the film does raise and answer, is that, it is possible to have been a victim and not to lose one’s humanity in order to recover, survive and thrive, an important lesson at this juncture in our history. – Diane Joy Schmidt, Editor, NM Jewish Journal.

Essay on My Underground Mother

By Marisa Fox

October 13, 2025

My friends and colleagues thought I lost my mind when I chose to spend my summer vacation traveling solo to Poland, instead of the usual week at the beach with my family. At the time I was working as a deputy editor at a fashion magazine with three small kids at home and hadn’t traveled alone outside of work trips since before I was married. But I was on a mission. An elderly relative had recently revealed a family secret that led me to believe my late mother had a hidden identity. I was determined to see if there was any there, there. The thought of traveling to a place my mother vowed to never revisit filled me with dread. I figured I’d visit her hometown, get my bearings, find a guide who could help me navigate their vital records and be done with it. But that would be the first of eight trips to Poland and several other locations I’d either never heard of or had on any sort of bucket list. I’d spend the next decade criss-crossing the globe in a race against time chasing down any lead or anybody who knew my mother and could help me resolve the burning question: who had my mother been and why had she erased her past?

Without giving everything away, I learned that the woman whose maiden name I thought was Tamar Fromer was born with an entirely different name, and that much of her early life story was equally fictitious. She mostly spoke of her youth as a freedom fighter in the underground in British mandate Palestine and on the front lines of Israel’s War of Independence. “I was a hero,” she’d often say, “never a victim.” By victim, my mother meant Holocaust survivor, which she claimed she most definitely was not. It didn’t take me long to figure out, this detail wasn’t exactly factual either. My mother had been a prisoner of a Nazi-run Jewish women’s camp called Gabersdorf. It was one of 10 Jewish women’s camps in an alpine village called Trutnov, Czech Republic, annexed by the Nazis as Sudetenland. I had never heard of Jewish women’s camps, and there had been so many. They were part of a vast, under-the-radar network of 177 forced labor camps where Jewish youth from the Polish-German corridor were exploited to fuel the Wehrmacht. There wasn’t much written about these camps or the plight of teenage Jewish girls who were abducted in the night from their hometown ghettoes and languished there for nearly five years. I had to see if any of them still existed. Pretty soon, I found myself sneaking behind the fence of a ghost factory compound where Gabersdorf once stood. The barracks had been torn down. A local told me he used the wood to build his cottage, which he proudly showed me. How does it feel to live in a house made from a concentration camp? I asked. He scurried off.

Everyone in the town seemed oblivious to the dark role their town played in World War II. I learned my mother and most of the Jewish teenage prisoners in the town’s camps toiled for 12+-hour shifts, turning raw flax into thread that was used to sew together German military uniforms. On the surface this doesn’t sound as horrific as accounts from Auschwitz, particularly because these weren’t death camps. There were no crematoria. But the threat of death loomed overhead, along with hunger, exhaustion, squalid living conditions, industrial accidents and the fear of being forgotten, doomed to live in a void of inhumanity and never getting to see their parents and families again. Still, these accounts barely explained why my mother concealed such a huge part of her past.

Then I found a camp journal written by 60 Gabersdorf inmates, including my mother. As I read their pages, some written with schoolgirl innocence, others with profanity and still others with dark irony, I began to understand why I’d never heard of Gabersdorf or the plight of its prisoners. It’s the narrative we now have come to expect when young women are taken captive by terrorists and are caught in the crosshairs of conflict. It’s the story of girls raped and killed by the Ottomans during the Armenian genocide, of Yazidi girls taken captive by ISIS in Iraq, of Boko Haram kidnaping Chibok girls in Nigeria, and of course of Jewish girls and women abducted from the Nova Festival and from their kibbutzim by Hamas.

I write this, of course, as I’m watching a split screen of President Trump declaring “the war is over,” while the 20 living hostages are being reunited with their ecstatic families, tears flowing, as I recognize the very long road ahead for them all. For them, the war is most definitely not over. They may be physically free, but true liberation will take years of confronting the sorts of harsh truths my mother buried. As Dr. Mor Forbin, a therapist who treats Nova Festival survivors, explained to me shortly after Oct. 7th: “Normally, when you’re in a dangerous situation, your body is programmed to do four things: fight, flight, freeze, or beg for your life. Your brain, which normally processes information, shuts down. All you’re left with is a shattered memory, a picture that you can’t quite piece together, that lives in the shadows and prevents you from functioning as you did.”

That’s why being able to shape a personal narrative of survival is a key to recovering. Being able to retrieve and assemble the shards of traumatic memory into a cohesive story means a survivor can control the trauma. It doesn’t control them. I think about the story my mother told about her life that was one that highlighted her heroism and excised the victimhood. It was a story she had to tell for her own self-preservation. Unlike the hospitals and therapists like Dr. Forbin full of compassion and caring, determined to treat and heal trauma survivors, my mother was released into a world with no empathy for the horrors she experienced. Survivors were called “damaged,” “soap” and denigrated as “lambs who went to the slaughter” without putting up a fight. For a woman like my mother who didn’t just defy the odds by fighting the British in Palestine and founding Israel, but also resisted the Nazis by documenting her experiences in a camp journal and vowing to prevail, creating a story that was empowering was her lifeline.

As Dr. Forbin also explained, helping survivors craft a story that emphasizes their agency and even how they saved lives can help alleviate the crushing guilt and shame they feel. I understand why my mother stuck by her narrative, and why her truth was vital to her. I don’t fault her for embellishing her story. It may not be my truth, but I didn’t live through her traumas. The irony, of course, is that by removing Gabersdorf from her story, my mother diminished just how heroic she truly had been. But early Israeli society wasn’t willing to hear her or any survivor out, only in recasting itself as a nation of indomitable warriors. October 7th taught us again that we’re hardly invincible, but it should also serve as a reminder that being victimized shouldn’t be a source of shame. We can hold both truths at the same time. One thing I’ve learned from making My Underground Mother is that the truth can take decades to unravel. At least for now, it’s time to let October 7th survivors tell the stories they need to tell, and for us to listen and ask questions later.

###

DIRECTOR’S BIO Marisa Fox, Writer, Director, Producer

An award-winning journalist, Fox has covered major news stories from 9/11 (New York Magazine, New York Newsday) to the opioid crisis (The New York Times), from the 2017 Women’s March and rollback of women’s rights (Ms.), the Muslim ban (Haaretz) to the COVID pandemic, January 6th and the rise of white supremacy (The Daily Beast, CNN, the Forward). She was a U.S. correspondent for Israeli newspaper Haaretz, specializing in gender, genocide, sexual trauma and extremism, and is a “she source” for the Women’s Media Center, started by Gloria Steinem. Throughout her 30-plus year career, she served as a deputy magazine editor and has written cover stories and lead features for The Chicago Tribune, LA Times, InStyle, O, Elle, Billboard and The Hollywood Reporter. She also was a television producer (FX, MTV, Vh1 and Channel 13-NYC) and a digital producer for Hearst, earning awards and nominations from the American Society of Magazine Editors.

My Underground Mother, Fox’s directorial debut, led her to curate one of the only women’s Holocaust monuments at the site of the former Gabersdorf camp in Trutnov, Czech Republic, and a digital exhibit of women’s testimonies with USC’s Shoah Foundation. Marisa cut her teeth in investigative journalism as a college intern at the Better Government Association and covered foreign affairs as a college intern for the Jerusalem Post’s Washington, DC bureau. She holds a Master’s and Bachelor’s of Science in Journalism and a BA in French Language & Literature from Northwestern University, earning a National Magazine Award for her master’s thesis publication Arts Chicago.

Read also: "Extinguished Lives" world-premier short documentary; Interview with filmmaker Roberta Grossman, SFIFF OFFICIAL SELECTION here

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

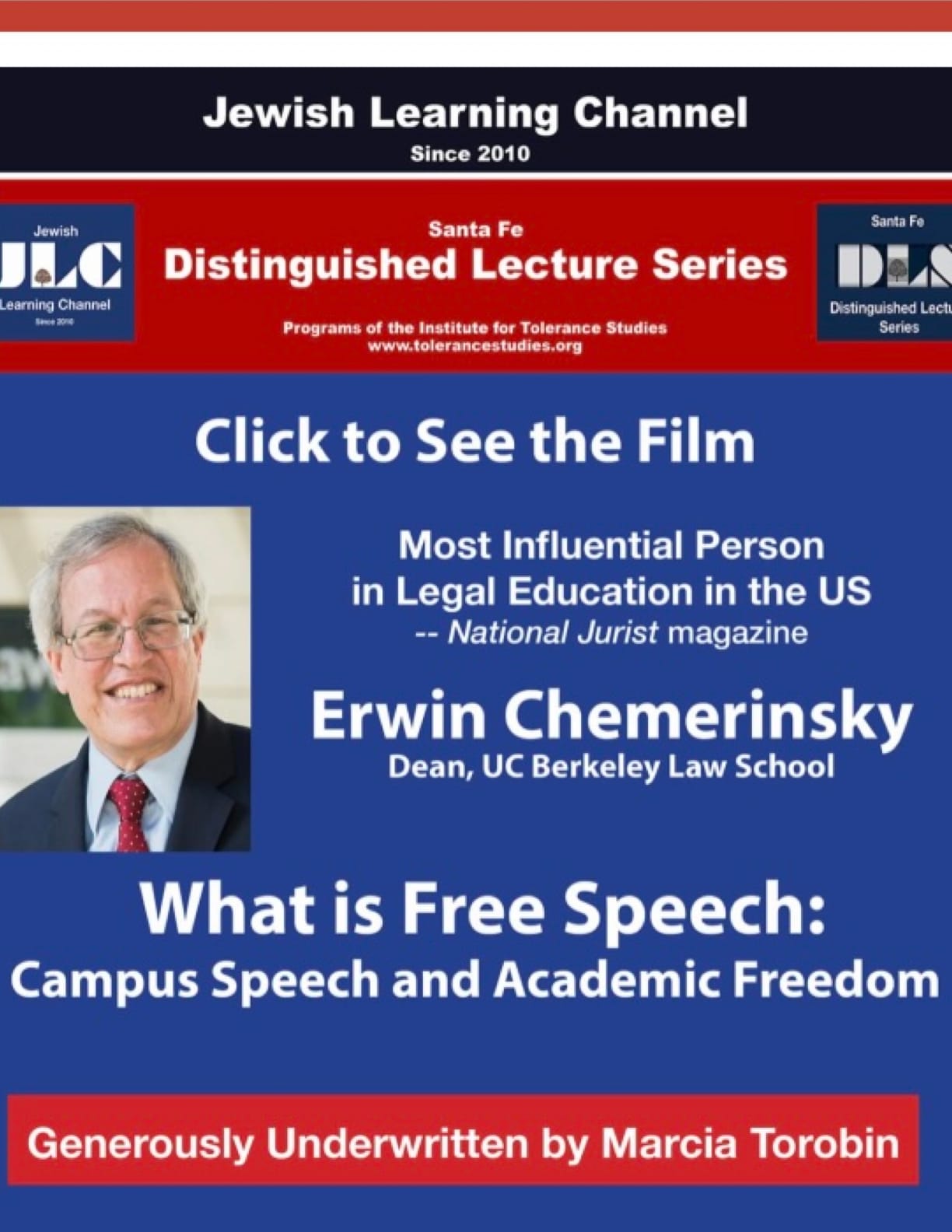

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

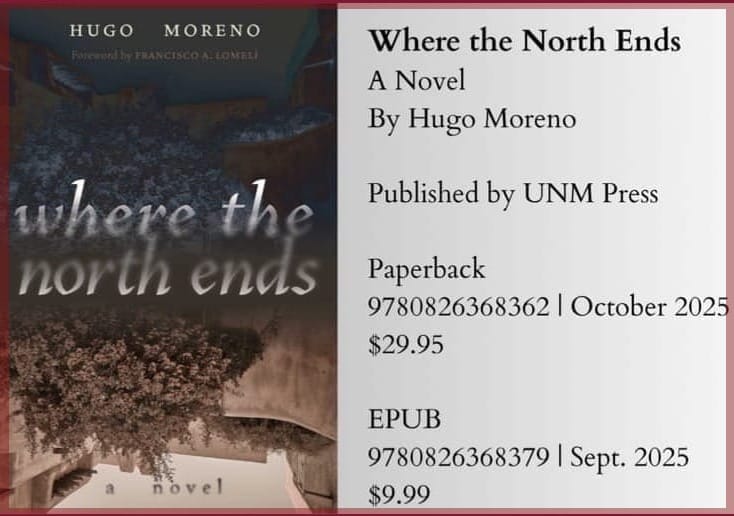

Where the North Ends, A Novel by Hugo Moreno

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.